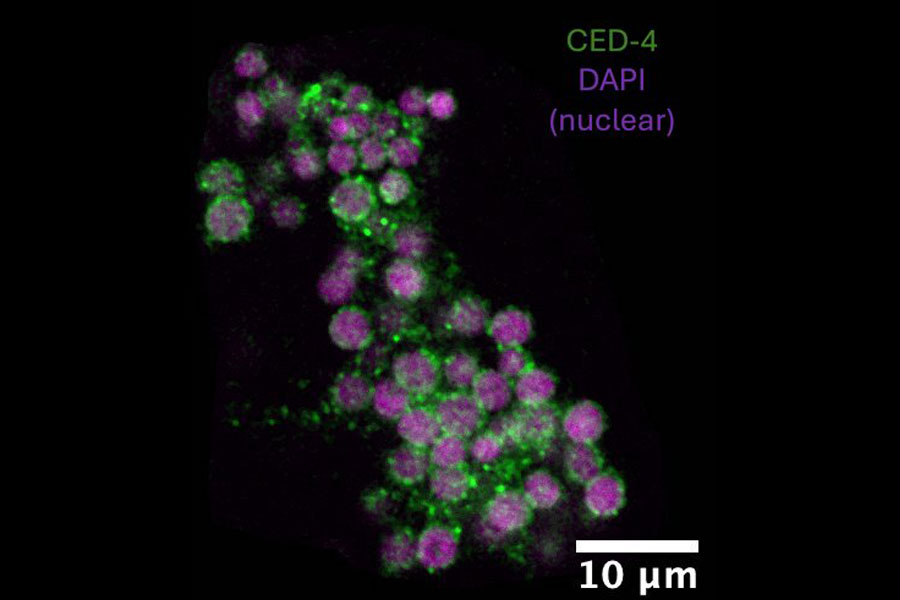

A major theme of Horvitz’s work is cell death. Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is pervasive in animal biology and important in certain human neurodegenerative diseases. Horvitz has shown that cell death is an active process, and that many of the genes that control the deaths of worm neurons have counterparts in the human brain. His discoveries might lead to new treatments for certain degenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s diseases, stroke and traumatic brain injury. In October 2002, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Horvitz, Sydney Brenner, and John E. Sulston “for their discoveries concerning genetic regulation of organ development and programmed cell death.” Watch Horvitz’s Nobel lecture below.

In addition to his studies of C. elegans, Horvitz also has a longstanding active interest in human neurodegenerative disease. He was a principal member of the team that in 1993 identified the first gene to cause familial ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease), and in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, he continues to work on the search for and analysis of additional ALS genes.

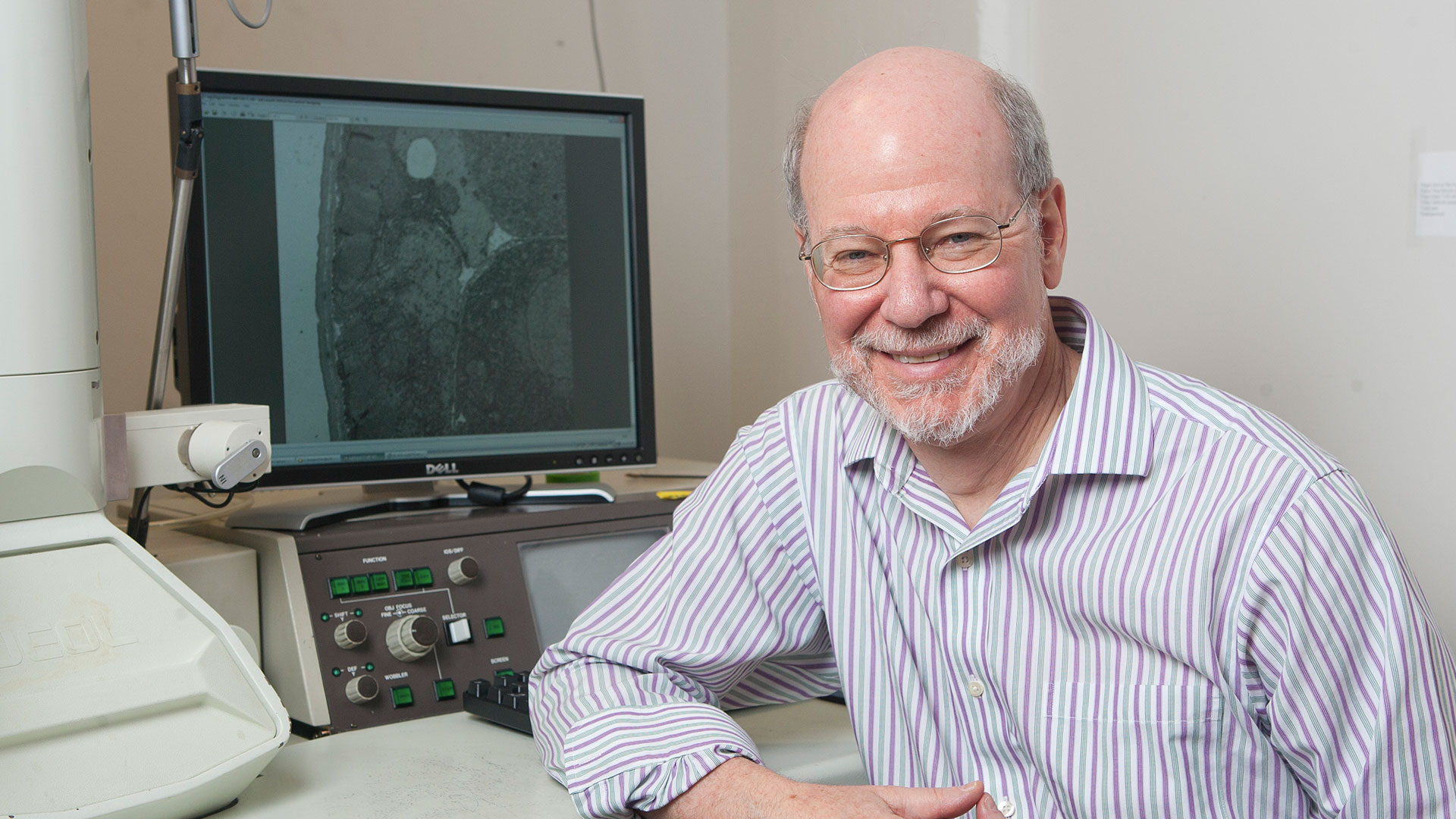

H. Robert Horvitz, a founding member of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research, is the David Koch Professor in the Department of Biology, a member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and an Investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Horvitz received his PhD from Harvard University in 1974, and has been a faculty member at MIT’s Department of Biology since 1978. In 2002 he shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering and characterizing genes controlling cell death in the nematode worm C. elegans.