Compulsive no more

By activating a brain circuit that controls compulsive behavior, McGovern neuroscientists have shown that they can block a compulsive behavior in mice — a result that could help researchers develop new treatments for diseases such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and Tourette’s syndrome.

About 1 percent of U.S. adults suffer from OCD, and patients usually receive antianxiety drugs or antidepressants, behavioral therapy, or a combination of therapy and medication. For those who do not respond to those treatments, a new alternative is deep brain stimulation, which delivers electrical impulses via a pacemaker implanted in the brain.

For this study, the MIT team used optogenetics to control neuron activity with light. This technique is not yet ready for use in human patients, but studies such as this one could help researchers identify brain activity patterns that signal the onset of compulsive behavior, allowing them to more precisely time the delivery of deep brain stimulation.

“You don’t have to stimulate all the time. You can do it in a very nuanced way,” says Ann Graybiel, an Institute Professor at MIT, a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research and the senior author of a Science paper describing the study.

The paper’s lead author is Eric Burguière, a former postdoc in Graybiel’s lab who is now at the Brain and Spine Institute in Paris. Other authors are Patricia Monteiro, a research affiliate at the McGovern Institute, and Guoping Feng, the James W. and Patricia T. Poitras Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and a member of the McGovern Institute.

Controlling compulsion

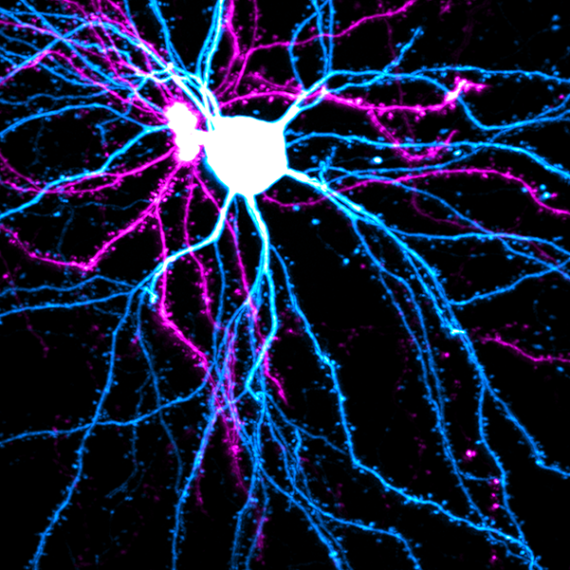

In earlier studies, Graybiel has focused on how to break normal habits; in the current work, she turned to a mouse model developed by Feng to try to block a compulsive behavior. The model mice lack a particular gene, known as Sapap3, that codes for a protein found in the synapses of neurons in the striatum — a part of the brain related to addiction and repetitive behavioral problems, as well as normal functions such as decision-making, planning and response to reward.

For this study, the researchers trained mice whose Sapap3 gene was knocked out to groom compulsively at a specific time, allowing the researchers to try to interrupt the compulsion. To do this, they used a Pavlovian conditioning strategy in which a neutral event (a tone) is paired with a stimulus that provokes the desired behavior — in this case, a drop of water on the mouse’s nose, which triggers the mouse to groom. This strategy was based on therapeutic work with OCD patients, which uses this kind of conditioning.

After several hundred trials, both normal and knockout mice became conditioned to groom upon hearing the tone, which always occurred just over a second before the water drop fell. However, after a certain point their behaviors diverged: The normal mice began waiting until just before the water drop fell to begin grooming. This type of behavior is known as optimization, because it prevents the mice from wasting unnecessary effort.

This behavior optimization never appeared in the knockout mice, which continued to groom as soon as they heard the tone, suggesting that their ability to suppress compulsive behavior was impaired.

The researchers suspected that failed communication between the striatum, which is related to habits, and the neocortex, the seat of higher functions that can override simpler behaviors, might be to blame for the mice’s compulsive behavior. To test this idea, they used optogenetics, which allows them to control cell activity with light by engineering cells to express light-sensitive proteins.

When the researchers stimulated light-sensitive cortical cells that send messages to the striatum at the same time that the tone went off, the knockout mice stopped their compulsive grooming almost totally, yet they could still groom when the water drop came. The researchers suggest that this cure resulted from signals sent from the cortical neurons to a very small group of inhibitory neurons in the striatum, which silence the activity of neighboring striatal cells and cut off the compulsive behavior.

“Through the activation of this pathway, we could elicit behavior inhibition, which appears to be dysfunctional in our animals,” Burguière says.

The researchers also tested the optogenetic intervention in mice as they groomed in their cages, with no conditioning cues. During three-minute periods of light stimulation, the knockout mice groomed much less than they did without the stimulation.

Scott Rauch, president and psychiatrist-in-chief of McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass., says the MIT study “opens the door to a universe of new possibilities by identifying a cellular and circuitry target for future interventions.”

“This represents a major leap forward, both in terms of delineating the brain basis of pathological compulsive behavior and in offering potential avenues for new treatment approaches,” adds Rauch, who was not involved in this study.

Graybiel and Burguière are now seeking markers of brain activity that could reveal when a compulsive behavior is about to start, to help guide the further development of deep brain stimulation treatments for OCD patients.

The research was funded by the Simons Initiative on Autism and the Brain at MIT, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative.