Bridging the gap between research and the classroom

MIT’s first-ever Science of Reading event brings together researchers and educators to discuss how to use research to improve literacy outcomes.

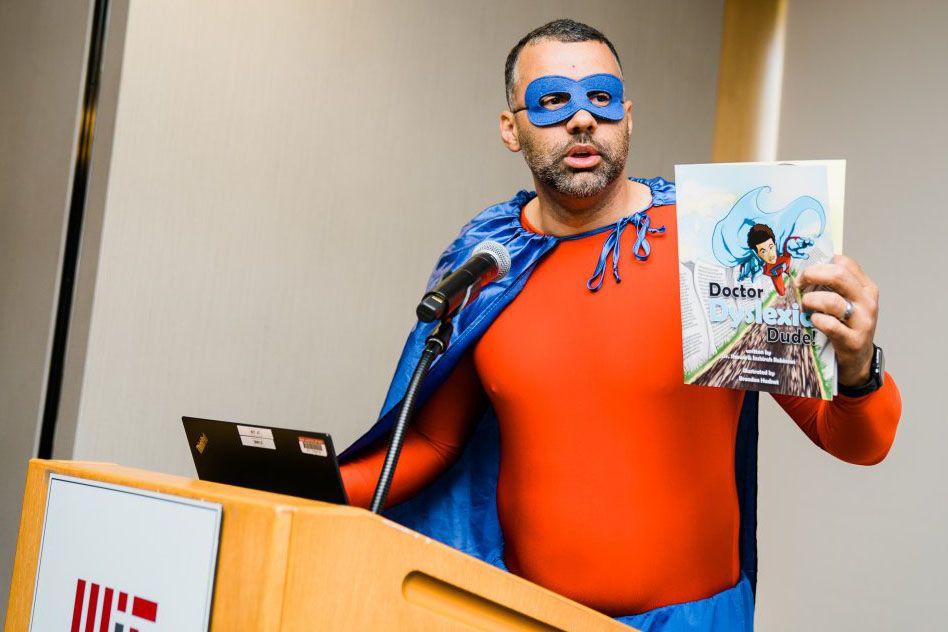

In a moment more reminiscent of a Comic-Con event than a typical MIT symposium, Shawn Robinson, senior research associate at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, helped kick off the first-ever MIT Science of Reading event dressed in full superhero attire as Doctor Dyslexia Dude — the star of a graphic novel series he co-created to engage and encourage young readers, rooted in his own experiences as a student with dyslexia.

The event, co-sponsored by the MIT Integrated Learning Initiative (MITili) and the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT, took place earlier this month and brought together researchers, educators, administrators, parents, and students to explore how scientific research can better inform educational practices and policies — equipping teachers with scientifically-based strategies that may lead to better outcomes for students.

Professor John Gabrieli, MITili director, explained the great need to focus the collective efforts of educators and researchers on literacy.

“Reading is critical to all learning and all areas of knowledge. It is the first great educational experience for all children, and can shape a child’s first sense of self,” he said. “If reading is a challenge or a burden, it affects children’s social and emotional core.”

A great divide

Reading is also a particularly important area to address because so many American students struggle with this fundamental skill. More than six out of every 10 fourth graders in the United States are not proficient readers, and changes in reading scores for fourth and eighth graders have increased only slightly since 1992, according to the National Assessment of Education Progress.

Gabrieli explained that, just as with biomedical research, where there can be a “valley of death” between basic research and clinical application, the same seems to apply to education. Although there is substantial current research aiming to better understand why students might have difficulty reading in the ways they are currently taught, the research often does not necessarily shape the practices of teachers — or how the teachers themselves are trained to teach.

This divide between the research and practical applications in the classroom might stem from a variety of factors. One issue might be the inaccessibility of research publications that are available for free to all — as well as the general need for scientific findings to be communicated in a clear, accessible, engaging way that can lead to actual implementation. Another challenge is the stark difference in pacing between scientific research and classroom teaching. While research can take years to complete and publish, teachers have classrooms full of students — all with different strengths and challenges — who urgently need to learn in real time.

Natalie Wexler, author of “The Knowledge Gap,” described some of the obstacles to getting the findings of cognitive science integrated into the classroom as matters of “head, heart, and habit.” Teacher education programs tend to focus more on some of the outdated psychological models, like Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, and less on recent cognitive science research. Teachers also have to face the emotional realities of working with their students, and might be concerned that a new approach would cause students to feel bored or frustrated. In terms of habit, some new, evidence-based approaches may be, in a practical sense, difficult for teachers to incorporate into the classroom.

“Teaching is an incredibly complex activity,” noted Wexler.

From labs to classrooms

Throughout the day, speakers and panelists highlighted some key insights gained from literacy research, along with some of the implications these might have on education.

Mark Seidenberg, professor of psychology at the University of Wisconsin at Madison and author of “Language at the Speed of Sight,” discussed studies indicating the strong connection between spoken and printed language.

“Reading depends on speech,” said Seidenberg. “Writing systems are codes for expressing spoken language … Spoken language deficits have an enormous impact on children’s reading.”

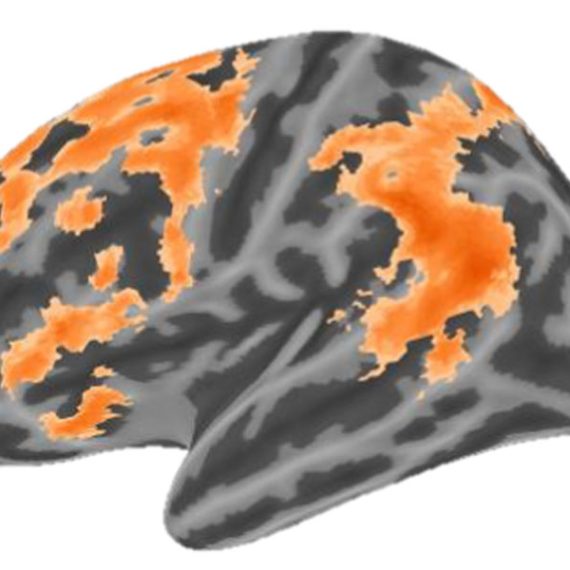

The integration of speech and reading in the brain increases with reading skill. For skilled readers, the patterns of brain activity (measured using functional magnetic resonance imaging) while comprehending spoken and written language are very similar. Becoming literate affects the neural representation of speech, and knowledge of speech affects the representation of print — thus the two become deeply intertwined.

In addition, researchers have found that the language of books, even for young children, include words and expressions that are rarely encountered in speech to children. Therefore, reading aloud to children exposes them to a broader range of linguistic expressions — including more complex ones that are usually only taught much later. Thus reading to children can be especially important, as research indicates that better knowledge of spoken language facilitates learning to read.

Although behavior and performance on tests are often used as indicators of how well a student can read, neuroscience data can now provide additional information. Neuroimaging of children and young adults identifies brain regions that are critical for integrating speech and print, and can spot differences in the brain activity of a child who might be especially at-risk for reading difficulties. Brain imaging can also show how readers’ brains respond to certain reading and comprehension tasks, and how they adapt to different circumstances and challenges.

“Brain measures can be more sensitive than behavioral measures in identifying true risk,” said Ola Ozernov-Palchik, a postdoc at the McGovern Institute.

Ozernov-Palchik hopes to apply what her team is learning in their current studies to predict reading outcomes for other children, as well as continue to investigate individual differences in dyslexia and dyslexia-risk using behavior and neuroimaging methods.

Identifying certain differences early on can be tremendously helpful in providing much-needed early interventions and tailored solutions. Many speakers noted the problem with the current “wait-to-fail” model of noticing that a child has a difficult time reading in second or third grade, and then intervening. Research suggests that earlier intervention could help the child succeed much more than later intervention.

Speakers and panelists spoke about current efforts, including Reach Every Reader (a collaboration between MITili, the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and the Florida Center for Reading Research), that seek to provide support to students by bringing together education practitioners and scientists.

“We have a lot of information, but we have the challenge of how to enact it in the real world,” said Gabrieli, noting that he is optimistic about the potential for the additional conversations and collaborations that might grow out of the discussions of the Science of Reading event. “We know a lot of things can be better and will require partnerships, but there is a path forward.”