Abnormal brain connectivity may precede schizophrenia onset

Study finds cerebellar differences linked to psychosis.

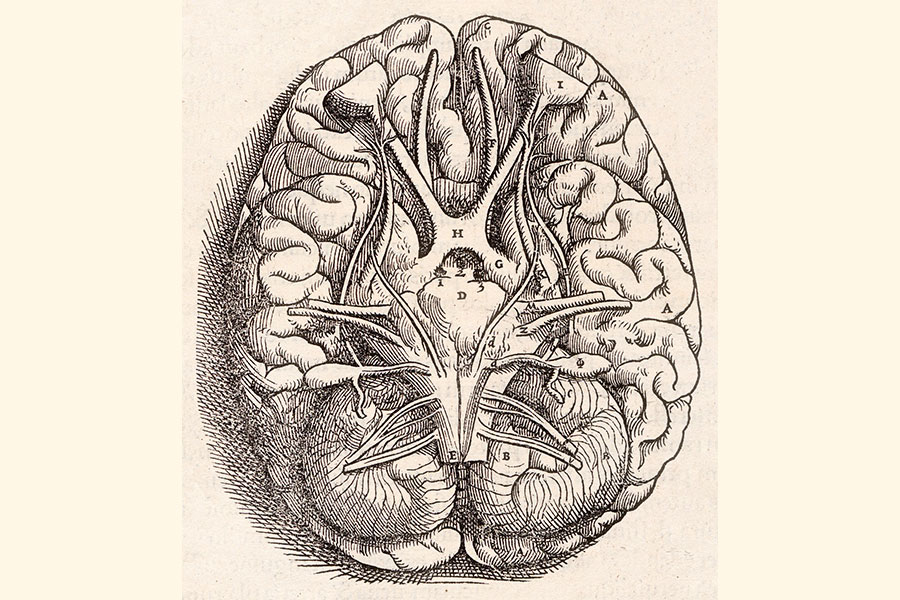

The cerebellum is named “little brain” for its distinctive structure. Although the cerebellum was long considered only for its role in maintaining the balance and timing of movements, it has become evident that it is also important for balanced thoughts and emotions, belying the diversity of functions that “little brain” implies.

In a new study published in Schizophrenia Bulletin, McGovern Research Affiliate and Northeastern University Professor of Psychiatry Susan Whitfield-Gabrieli shows for the first time that cerebellar dysfunction actually precedes the onset of psychosis in schizophrenia, a brain disorder characterized by severe thought and emotional imbalances.

“This study exemplifies the concept of “neuroprediction,” the discovery of brain-based biomarkers that allow early detection and therefore early intervention for mental disorders,” says Whitfield-Gabrieli.

Cerebellar connectivity and schizophrenia

Early evidence that the cerebellum is involved in more than movement came from numerous reports that people with brain damage originating in the cerebellum can have severely disordered thought processes. Now cerebellar abnormalities have been identified in numerous neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric conditions including autism, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Alzheimer’s disease, and schizophrenia.

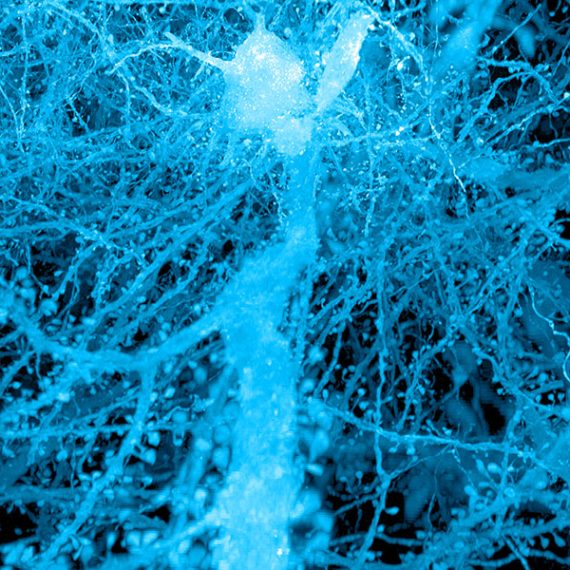

Whitfield-Gabrieli has focused on how symptoms in these disorders correlate with how well the cerebellum is connected to other brain regions, including regions of the cerebral cortex, the characteristically-folded, outer part of the brain. Active connections in the brain of people who are resting or who are engaged in a mental task can be found by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a brain scanning technique that detects when and where oxygen is being used by cells. If oxygen usage in two brain regions consistently peaks at the same time while someone is in the scanner, they are considered to be functionally connected.

Connectivity differences prior to psychosis

In her new study, Whitfield-Gabrieli explored whether brain scans could reveal cerebellar abnormalities in people at-risk for schizophrenia.

To do this, she and her colleagues compared cerebellar connectivity among at-risk adolescents and young adults who went on to develop psychosis within the following year versus those that remained stable or improved. The at-risk participants were identified in an international collaboration called the Shanghai At Risk for Psychosis (SHARP) program that recruited people who were seeking help at China’s largest outpatient mental health center. Of the 144 adolescents and young adults at-risk for schizophrenia at the outset of the study, 23 went on to develop the disorder. Notably, this group showed fMRI patterns of cerebellar dysfunction at the outset of the study, before they developed psychosis.

Abnormal brain architecture

All of the brain scans were evaluated to determine the degree to which three specific cerebellar regions were connected to the cerebral cortex, a brain region that does not finish development until young adulthood. The cerebellar regions of interest to Whitfield-Gabrieli are part of the “dentate nuclei,” so named because they look like a set of jagged teeth. Neurons in the dentate nuclei serve to integrate inputs from the rest of the cerebellum and send the compiled information out to the rest of the brain. Whitfield-Gabrieli and colleagues divided the dentate nuclei into three zones according to what parts of the cerebral cortex they are functionally connected to while people are relaxing, doing visual tasks, or engaging in a motor task or receiving some sort of stimulation.

The team found abnormal connectivity for all three zones of the dentate nuclei in the individuals who later went on to develop schizophrenia. Since the connectivity patterns varied across regions within the three zones, with some regions over-connected and others under-connected to the cerebral cortex in the group that developed psychosis, separated high-resolution analyses of the different connections was key.

Previous work established that cerebellar abnormalities are associated with schizophrenia but this study is the first to show that functional connections between the deep cerebellar nuclei and the cerebral cortex might precede disease onset. “Treatments for mental disorders are inherently reactive to suffering and incapacity. A proactive approach by which abnormal brain architecture is identified prior to clinical diagnosis has the potential to prevent suffering by helping people before they become ill, one of my ultimate goals” said Whitfield-Gabrieli.

This study was supported by the Poitras Center for Psychiatric Disorders Research at MIT), US National Institute of Mental Health (R21 MH 093294, R01 MH 101052, R01 MH 111448, and R01 MH 64023), Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2016 YFC 1306803), European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 749201 and by a VA Merit Award.