Having more conversations to boost brain development

When families increase dialogue between children and adults, children’s cognitive skills improve quickly as language-processing parts of the brain grow.

Engaging children in more conversation may be all it takes to strengthen language processing networks in their brains, according to a new study by MIT scientists.

Childhood experiences, including language exposure, have a profound impact on the brain’s development. Now, scientists led by McGovern Institute investigator John Gabrieli have shown that when families change their communication style to incorporate more back-and-forth exchanges between child and adult, key brain regions grow and children’s language abilities advance. Other parts of the brain may be impacted, as well.

In a study of preschool and kindergarten-aged children and their families, Gabrieli, Harvard postdoctoral researcher Rachel Romeo, and colleagues found that increasing conversation had a measurable impact on children’s brain structure and cognition within just a few months. “In just nine weeks, fluctuations in how often parents spoke with their kids appear to make a difference in brain development, language development, and executive function development,” Gabrieli says. The team’s findings are reported in the June issue of the journal Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience.

“We’re excited because this adds a little more evidence to the idea that [the brain] is malleable,” adds Romeo, who is now an assistant professor at the University of Maryland College Park.

“It suggests that in a relatively short period of time, the brain can change in positive ways,” says Romeo.

30 million word gap

In the 1990s, researchers determined that there are dramatic discrepancies in the language that children are exposed to early in life. They found that children from high-income families heard about 30 million more words during their first three years than children from lower-income families—and those exposed to more language tended to do better on tests of language development, vocabulary, and reading comprehension.

In 2018, Gabrieli and Romeo found that it was not the volume of language that made a difference, however, but instead the extent to which children were engaged in conversation. They measured this by counting the number of “conversational turns” that children experienced over a few days—that is, the frequency with which dialogue switched between child and adult. When they compared the brains of children who experienced significantly different levels of these conversational turns, they found structural and functional differences in regions known to be involved in language and speech.

After observing these differences, the researchers wanted to know whether altering a child’s language environment would impact their brain’s future development. To find out, they enrolled the families of fifty-two children between the ages of four and seven in a study, and randomly assigned half of the families to participate in a nine-week parent training program. While the program did not focus exclusively on language, there was an emphasis on improving communication, and parents were encouraged to engage in meaningful dialogues with their children.

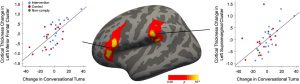

Romeo and colleagues sent families home with audio recording devices to capture all of the language children were exposed to over two full days, first at the outset of the program and again after the nine-week training was complete. When they analyzed the recordings, they found that in many families, conversation between children and their parents had increased—and children who experienced the greatest increase in conversational turns showed the greatest improvements in language skills as well as in executive functions—a set of skills that includes memory, attention, and self-control.

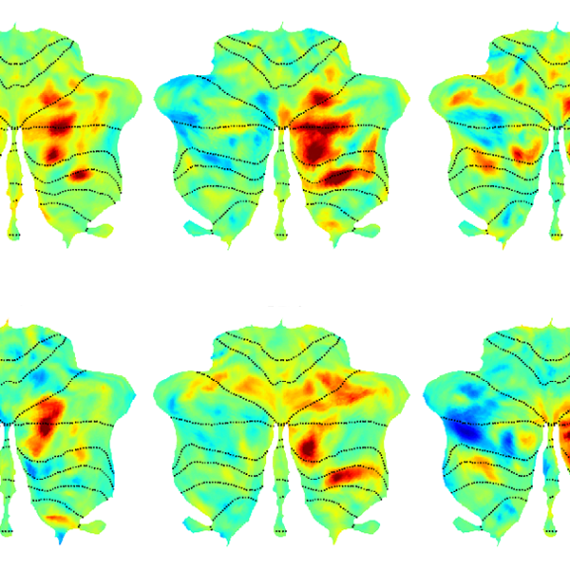

MRI scans showed that over the nine-week study, these children also experienced the most growth in two key brain areas: a sound processing center called the supramarginal gyrus and a region involved in language processing and speech production called Broca’s area. Intriguingly, these areas are very close to parts of the brain involved in executive function and social cognition.

“The brain networks for executive functioning, language, and social cognition are deeply intertwined and going through these really important periods of development during this preschool and transition-to-school period,” Romeo says. “Conversational turns seem to be going beyond just linguistic information. They seem to be about human communication and cognition at a deeper level. I think the brain results are suggestive of that, because there are so many language regions that could pop out, but these happen to be language regions that also are associated with other cognitive functions.”

Talk more

Gabrieli and Romeo say they are interested in exploring simple ways—such a web or smartphone-based tools—to support parents in communicating with their children in ways that foster brain development. It’s particularly exciting, Gabrieli notes, that introducing more conversation can impact brain development when at the age when children are preparing to begin school.

“Kids who arrive to school school-ready in language skills do better in school for years to come,” Gabrieli says. “So I think it’s really exciting to be able to see that the school readiness is so flexible and dynamic in nine weeks of experience.”

“We know this is not a trivial ask of people,” he says. “There’s a lot of factors that go into people’s lives— their own prior experiences, the pressure of their circumstances. But it’s a doable thing. You don’t have to have an expensive tutor or some deluxe pre-K environment. You can just talk more with your kid.”