All the connections

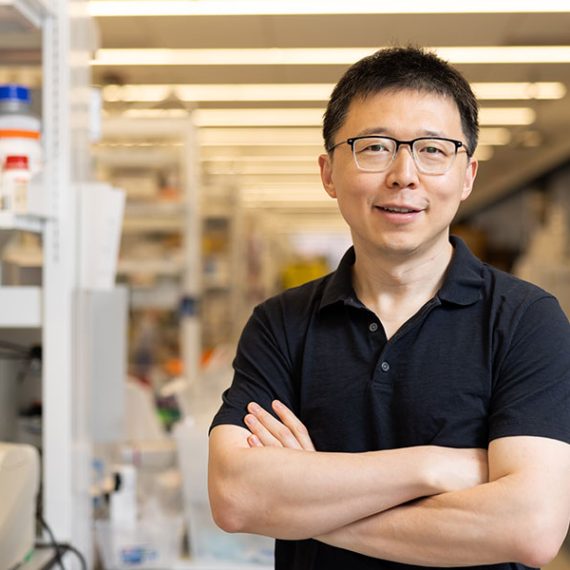

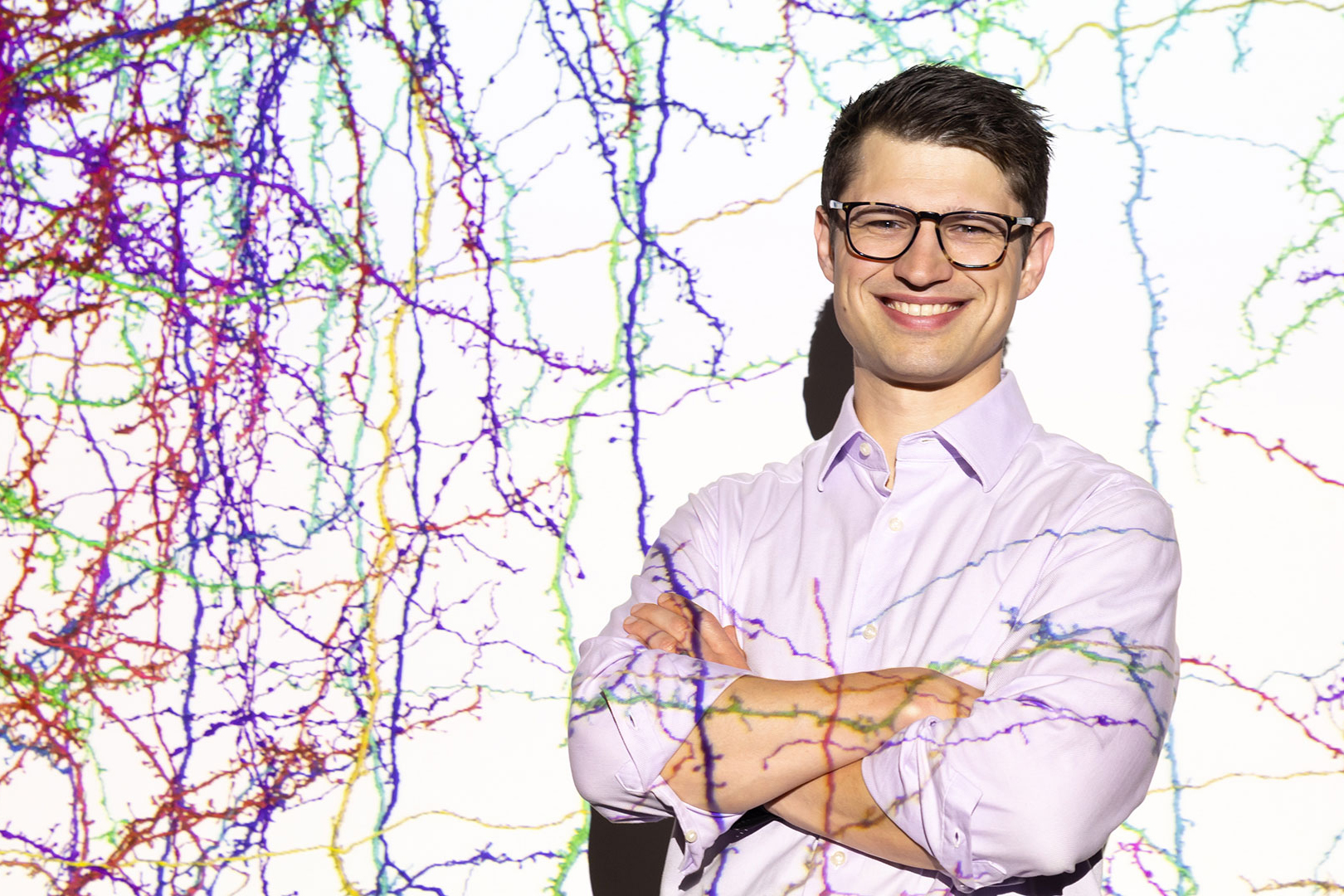

McGovern's newest investigator, Sven Dorkenwald, is looking for meaning in maps of the brain.

Neuroscientists today have the most spectacular views of brains that the field has ever seen. Modern microscopes can reveal extraordinary levels of detail, offering scientists another piece of the vast and intricate puzzle of how neurons interconnect.

A comprehensive wiring diagram of the brain — its connectome — is an atlas for neuroscientists, guiding investigations into how neural circuitry works. Microscope images are the raw data for generating that atlas, but it takes powerful computers and shrewd scientists, like the McGovern Institute’s newest investigator, Sven Dorkenwald, to make sense of it all.

A monumental task

Many disorders of the human brain are related to breakdowns that affect the connections of neurons with one another. An atlas will help researchers identify and study the function of those connections — down to the level of synapses — and explore what happens when things go wrong. When researchers understand which brain cells interact with one another, they can ask more sophisticated questions about how those cells work together to process information, store memories, or modulate our emotions.

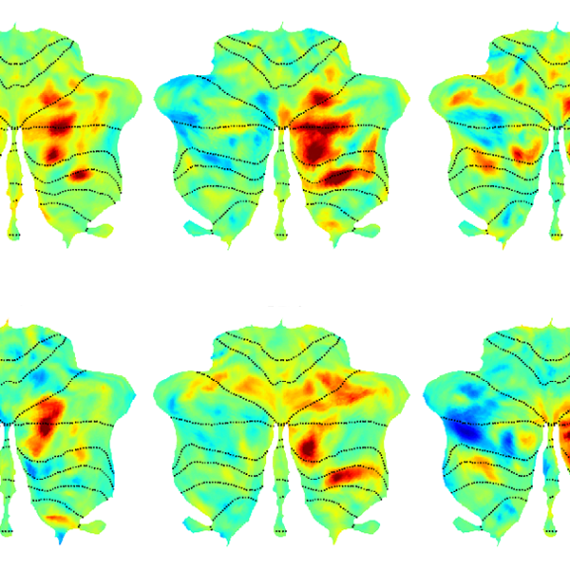

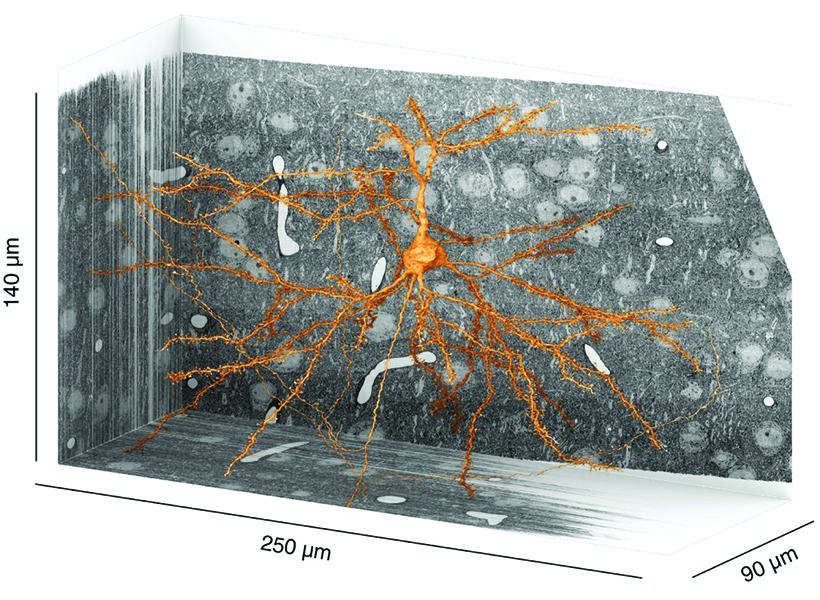

Until recently, generating a complete connectome for any animal was nearly impossible. Electron microscopes capture fine details of cellular structures, down to the slender branches and tiny protrusions that neurons use to reach out and communicate with one another. But to see those features clearly, microscopes have to zoom way in, focusing solely on a thin slice of one small part of the brain at a time.

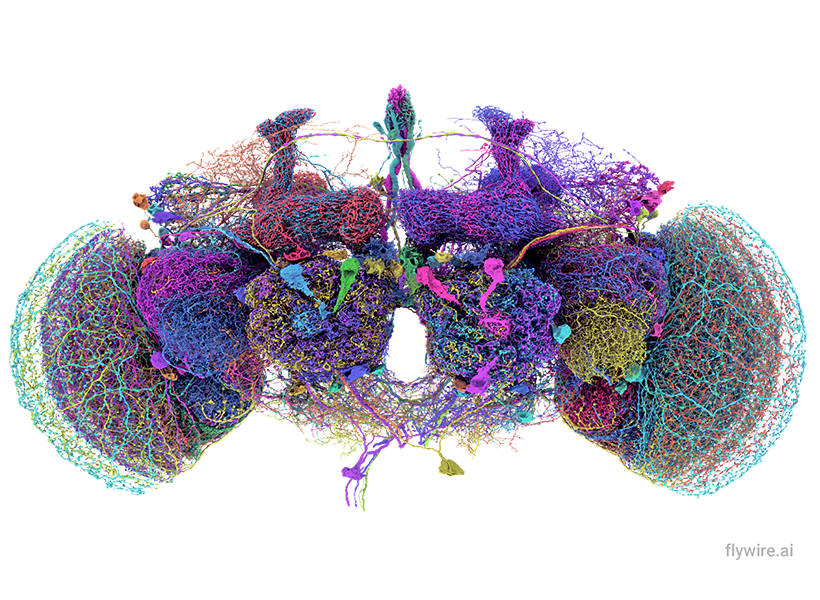

Isolated images like these don’t reveal much on their own. They are a jumble of bits and pieces of cells — a cross-section removed from the context of its surroundings. Neurons’ paths must be traced through millions of images to reconstruct the brain’s three-dimensional networks and ultimately, reveal how its individual cells connect with one another. This is a monumental task, because even the poppy seed-sized brain of a fruit fly contains more than 50 million synapses.

Remarkably, all of those connections in the fruit fly’s tiny brain are now mapped, thanks in large part to Dorkenwald’s efforts as a PhD student at Princeton University. Together with professors Sebastian Seung and Mala Murthy, Dorkenwald spearheaded FlyWire, a consortium of hundreds of scientists who charted the circuitry, following the fly’s neurons through 21 million microscope images. Neuroscientists around the world now use that connectome, which was completed in 2024, to understand how information flows through the fruit fly brain and shed light on parallel processes in our own brains.

AI tools and teamwork

Getting from millions of microscope images to a complete wiring diagram of the fly brain required the development of innovative new tools and an extraordinary level of teamwork. Dorkenwald, who was recently named one of STAT’s 2025 Wunderkinds, an award that celebrates outstanding early-career scientists, was instrumental in both.

Dorkenwald’s first experience mapping neural circuits was as a physics undergraduate at Heidelberg University, tracing neurons in a targeted area of a zebra finch brain. The lab wanted a map to help them understand how birds learn and repeat their courtship songs. Tracing neurons was, at the time, painstaking work. Dorkenwald and his fellow students would manually follow the path of a single cell as it passed across adjacent microscope images, noting each branch point to return to for further mapping.

Today, the process has accelerated greatly, with artificial intelligence (AI) tools taking over most of the work. But those tools make mistakes, and it’s up to humans to find and correct them.

Dorkenwald encountered this obstacle as a graduate student in Seung’s lab at Princeton, where he studied computer science and neuroscience. Before FlyWire, the lab was part of a collaborative effort called the MICrONS consortium, which included teams at the Allen Institute and Baylor College of Medicine, that aimed to map all the connections within a cubic millimeter of the mouse visual cortex. Size alone made this a daunting task: a cubic millimeter of a mouse brain is ten times the size of a fly brain. Dorkenwald and colleagues developed the infrastructure the team needed to proofread and analyze the same dataset.

Their system, which they call CAVE (Connector Annotation Versioning Engine), allowed the team to expand its proofreading community far beyond the three labs who drove the project, involving many neuroscientists who were interested in different parts of the circuitry. “We basically opened up this dataset to anybody who wanted to join,” Dorkenwald says. When they later deployed CAVE to enable community-wide proofreading for the fly connectome, citizen scientists got involved, and paid proofreaders joined the mix to fill in gaps in the map. It has since become an essential tool in the connectomics field.

The MICrONS consortium ultimately reconstructed more than a half billion synapses in that cubic millimeter of mouse tissue. What’s more, researchers added another level of information to the map, incorporating data on neuronal activity recorded from the very mouse whose brain had been imaged for the project enabling new studies that relate a circuit structure with its function. These results, published earlier this year, represent another milestone for the field.

Dorkenwald says this newly mapped piece of the mouse connectome is large enough that scientists can begin to see and analyze neural circuits. Still, zeroing in on a cubic millimeter within the mouse’s pea-sized brain means most of what’s visible is parts of cells, which can leave scientists struggling to identify exactly what they’re looking at. Dorkenwald says bits of cells can reveal their identities with their particular shapes and ultrastructural contents, such as vesicles and mitochondria. However, humans can’t necessarily make sense of these subtle features on their own. An AI tool that he developed called SegCLR (segmentation-guided contrastive learning of representations) decodes these clues.

SegCLR is one way Dorkenwald is applying his computational expertise to make sense of connectomes and integrate new kinds of information into the maps — work that he continued as a fellow at the Allen Institute after earning his PhD at Princeton.

“A connectome alone is not enough,” he says. “If you would just look at a connectome of a brain, it would look like white noise at first. You have to put order into the system to understand its parts.”

Searching for meaning

In January 2026, Dorkenwald will join MIT as an assistant professor of brain and cognitive sciences and an investigator at the McGovern Institute. He will be digging into the connectomes he has helped produce, developing new computational approaches to look for organizational principles within the circuitry. “We will be asking hard questions about the circuits we reconstruct,” he says. “The connections that we are seeing contribute to interesting and important computations. What are the circuit motifs that allow them to do that? What’s the architecture of the circuit within layers, across layers, and ultimately, across regions? That is what I want to get at.”

While there’s plenty of data to work with, he’s also eager to continue scaling up connectomics. He thinks a complete connectome of the mouse brain is achievable within 10 to 15 years — but it’s going to require a lot of collaboration. “The area we’re working in is still very new,” he says. “There’s a lot of room to approach things in new ways and solve problems that are very large, in ways that move an entire field forward.”

As the technology advances, Dorkenwald plans to compare connectomes across individuals to better understand variations in circuitry, including the changes that occur in individuals with neurological or psychiatric disorders.

To help make that possible, he’s going to design new AI approaches to automate proofreading, which remains a bottleneck for connectomics. Even a community-wide effort will be too slow to manually proofread a map of the entire mouse brain, so this step will also need to be automated. For this, Dorkenwald will turn to data from past proofreaders, who have already made millions of manual edits to connectomes. Dorkenwald plans to train AI tools to mimic their work.

Dorkenwald says his career in connectomics began with a sense of wonder, back when he was tracing neurons through images of the zebra finch brain. “Every time you asked about what is in there, and nobody knew, there was so much that felt undiscovered,” he remembers. Now, he’s making all the information hidden within those images more accessible: “If we can just extract it, I think we can make sense of it.”