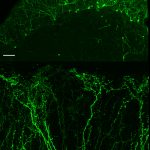

To view the viral core image gallery, please click on one of the thumbnail images below.

Author: Julie Pryor

McGovern Institute Holiday Greeting 2013

Wishing you a ball this holiday season — from your friends at the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT!

Jisong Guan: McGovern Institute 2013 Fall Symposium

Jisong Guan, Tsinghua University

“Chasing the memory traces in mammalian cortex”

On November 4, the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT hosted a joint symposium with the IDG/McGovern Institutes at Beijing Normal University, Peking University, and Tsinghua University. Guest speakers gave talks on subjects ranging from learning and memory to the neurobiology of disease. The symposium was sponsored by the McGovern Institutes and Hugo Shong.

Yichang Jia: McGovern Institute 2013 Fall Symposium

Yichang Jia, Tsinghua University

“Disease mechanisms underlying neurodegeneration caused by RNA metabolism abnormalities”

On November 4, the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT hosted a joint symposium with the IDG/McGovern Institutes at Beijing Normal University, Peking University, and Tsinghua University. Guest speakers gave talks on subjects ranging from learning and memory to the neurobiology of disease. The symposium was sponsored by the McGovern Institutes and Hugo Shong.

Lihong Wang: McGovern Institute 2013 Fall Symposium

Lihong Wang, Tsingua University

“The neural correlates of trait rumination?”

On November 4, the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT hosted a joint symposium with the IDG/McGovern Institutes at Beijing Normal University, Peking University, and Tsinghua University. Guest speakers gave talks on subjects ranging from learning and memory to the neurobiology of disease. The symposium was sponsored by the McGovern Institutes and Hugo Shong.

Kewei Wang: McGovern Institute 2013 Fall Symposium

Kewei Wang

“Targeting voltage-gated Kv7/KCNQ K+ channels for therapeutic potential of neuropsychiatric disorders”

On November 4, the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT hosted a joint symposium with the IDG/McGovern Institutes at Beijing Normal University, Peking University, and Tsinghua University. Guest speakers gave talks on subjects ranging from learning and memory to the neurobiology of disease. The symposium was sponsored by the McGovern Institutes and Hugo Shong.

Liang Li: McGovern Institute 2013 Fall Symposium

Liang Li, Peking University

“Informational masking of speech in people with schizophrenia”

On November 4, the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT hosted a joint symposium with the IDG/McGovern Institutes at Beijing Normal University, Peking University, and Tsinghua University. Guest speakers gave talks on subjects ranging from learning and memory to the neurobiology of disease. The symposium was sponsored by the McGovern Institutes and Hugo Shong.

McGovern Institute Snowball Fight

McGovern faculty, researchers and staff participated in a snowball fight in the Bldg 46 atrium. The scene was filmed for the annual McGovern holiday video greeting.

See below for a photo gallery of the event. All photos courtesy of Justin Knight.

2013 Holiday Party

Sheng Li: McGovern Institute 2013 Fall Symposium

Sheng Li, Peking University

“Reward modulation of attention & working memory in the human brain.”

On November 4, the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT hosted a joint symposium with the IDG/McGovern Institutes at Beijing Normal University, Peking University, and Tsinghua University. Guest speakers gave talks on subjects ranging from learning and memory to the neurobiology of disease. The symposium was sponsored by the McGovern Institutes and Hugo Shong.