When an election result is disputed, people who are skeptical about the outcome may be swayed by figures of authority who come down on one side or the other. Those figures can be independent monitors, political figures, or news organizations. However, these “debunking” efforts don’t always have the desired effect, and in some cases, they can lead people to cling more tightly to their original position.

Neuroscientists and political scientists at MIT and the University of California at Berkeley have now created a computational model that analyzes the factors that help to determine whether debunking efforts will persuade people to change their beliefs about the legitimacy of an election. Their findings suggest that while debunking fails much of the time, it can be successful under the right conditions.

For instance, the model showed that successful debunking is more likely if people are less certain of their original beliefs and if they believe the authority is unbiased or strongly motivated by a desire for accuracy. It also helps when an authority comes out in support of a result that goes against a bias they are perceived to hold: for example, Fox News declaring that Joseph R. Biden had won in Arizona in the 2020 U.S. presidential election.

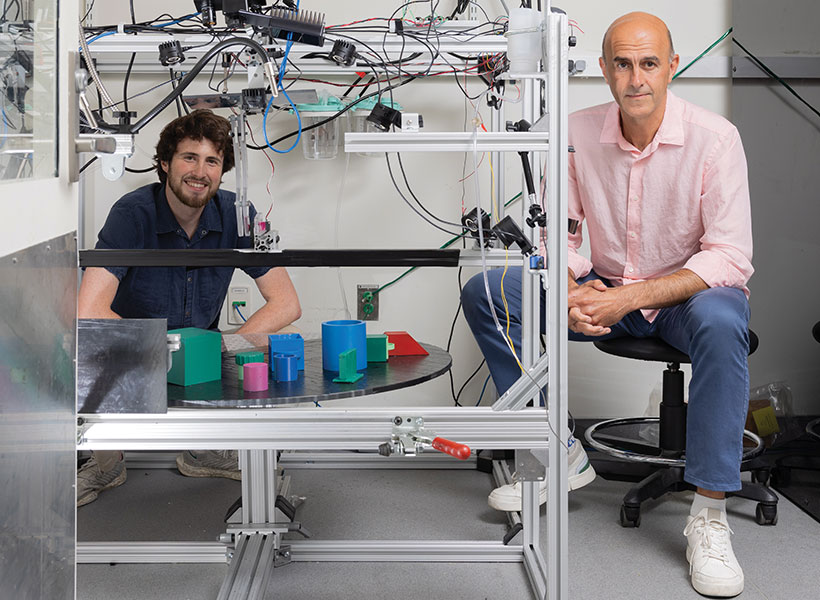

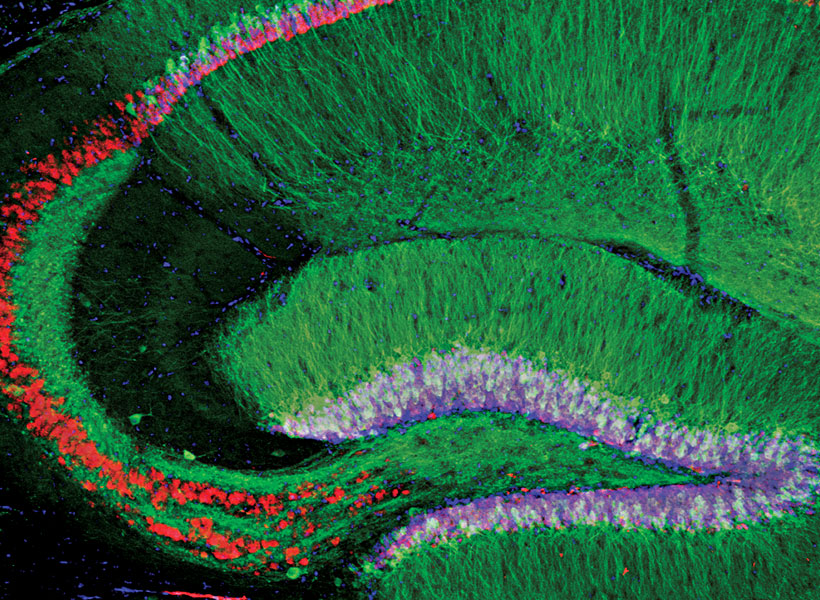

“When people see an act of debunking, they treat it as a human action and understand it the way they understand human actions — that is, as something somebody did for their own reasons,” says Rebecca Saxe, the John W. Jarve Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research, and the senior author of the study. “We’ve used a very simple, general model of how people understand other people’s actions, and found that that’s all you need to describe this complex phenomenon.”

The findings could have implications as the United States prepares for the presidential election taking place on Nov. 5, as they help to reveal the conditions that would be most likely to result in people accepting the election outcome.

MIT graduate student Setayesh Radkani is the lead author of the paper, which appears today in a special election-themed issue of the journal PNAS Nexus. Marika Landau-Wells PhD ’18, a former MIT postdoc who is now an assistant professor of political science at the University of California at Berkeley, is also an author of the study.

Modeling motivation

In their work on election debunking, the MIT team took a novel approach, building on Saxe’s extensive work studying “theory of mind” — how people think about the thoughts and motivations of other people.

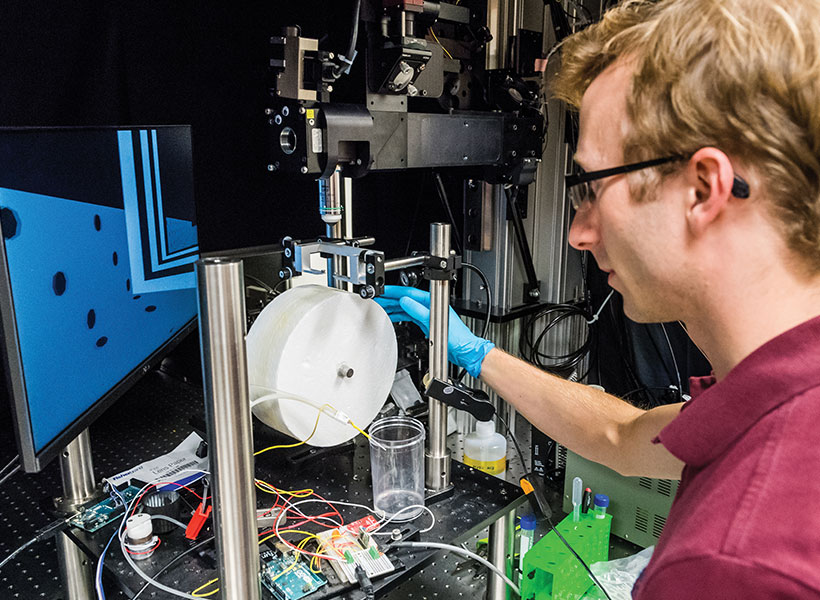

As part of her PhD thesis, Radkani has been developing a computational model of the cognitive processes that occur when people see others being punished by an authority. Not everyone interprets punitive actions the same way, depending on their previous beliefs about the action and the authority. Some may see the authority as acting legitimately to punish an act that was wrong, while others may see an authority overreaching to issue an unjust punishment.

Last year, after participating in an MIT workshop on the topic of polarization in societies, Saxe and Radkani had the idea to apply the model to how people react to an authority attempting to sway their political beliefs. They enlisted Landau-Wells, who received her PhD in political science before working as a postdoc in Saxe’s lab, to join their effort, and Landau suggested applying the model to debunking of beliefs regarding the legitimacy of an election result.

The computational model created by Radkani is based on Bayesian inference, which allows the model to continually update its predictions of people’s beliefs as they receive new information. This approach treats debunking as an action that a person undertakes for his or her own reasons. People who observe the authority’s statement then make their own interpretation of why the person said what they did. Based on that interpretation, people may or may not change their own beliefs about the election result.

Additionally, the model does not assume that any beliefs are necessarily incorrect or that any group of people is acting irrationally.

“The only assumption that we made is that there are two groups in the society that differ in their perspectives about a topic: One of them thinks that the election was stolen and the other group doesn’t,” Radkani says. “Other than that, these groups are similar. They share their beliefs about the authority — what the different motives of the authority are and how motivated the authority is by each of those motives.”

The researchers modeled more than 200 different scenarios in which an authority attempts to debunk a belief held by one group regarding the validity of an election outcome.

Each time they ran the model, the researchers altered the certainty levels of each group’s original beliefs, and they also varied the groups’ perceptions of the motivations of the authority. In some cases, groups believed the authority was motivated by promoting accuracy, and in others they did not. The researchers also altered the groups’ perceptions of whether the authority was biased toward a particular viewpoint, and how strongly the groups believed in those perceptions.

Building consensus

In each scenario, the researchers used the model to predict how each group would respond to a series of five statements made by an authority trying to convince them that the election had been legitimate. The researchers found that in most of the scenarios they looked at, beliefs remained polarized and in some cases became even further polarized. This polarization could also extend to new topics unrelated to the original context of the election, the researchers found.

However, under some circumstances, the debunking was successful, and beliefs converged on an accepted outcome. This was more likely to happen when people were initially more uncertain about their original beliefs.

“When people are very, very certain, they become hard to move. So, in essence, a lot of this authority debunking doesn’t matter,” Landau-Wells says. “However, there are a lot of people who are in this uncertain band. They have doubts, but they don’t have firm beliefs. One of the lessons from this paper is that we’re in a space where the model says you can affect people’s beliefs and move them towards true things.”

Another factor that can lead to belief convergence is if people believe that the authority is unbiased and highly motivated by accuracy. Even more persuasive is when an authority makes a claim that goes against their perceived bias — for instance, Republican governors stating that elections in their states had been fair even though the Democratic candidate won.

As the 2024 presidential election approaches, grassroots efforts have been made to train nonpartisan election observers who can vouch for whether an election was legitimate. These types of organizations may be well-positioned to help sway people who might have doubts about the election’s legitimacy, the researchers say.

“They’re trying to train to people to be independent, unbiased, and committed to the truth of the outcome more than anything else. Those are the types of entities that you want. We want them to succeed in being seen as independent. We want them to succeed as being seen as truthful, because in this space of uncertainty, those are the voices that can move people toward an accurate outcome,” Landau-Wells says.

The research was funded, in part, by the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation and the Guggenheim Foundation.