The following news is adapted from a press release issued in conjunction with Harvard Medical School.

Charles R. Broderick, an alumnus of MIT and Harvard University, has made gifts to both alma maters to support fundamental research into the effects of cannabis on the brain and behavior.

The gifts, totaling $9 million, represent the largest donation to date to support independent research on the science of cannabinoids. The donation will allow experts in the fields of neuroscience and biomedicine at MIT and Harvard Medical School to conduct research that may ultimately help unravel the biology of cannabinoids, illuminate their effects on the human brain, catalyze treatments, and inform evidence-based clinical guidelines, societal policies, and regulation of cannabis.

Lagging behind legislation

With the increasing use of cannabis both for medicinal and recreational purposes, there is a growing concern about critical gaps in knowledge.

In 2017, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine issued a report calling upon philanthropic organizations, private companies, public agencies and others to develop a “comprehensive evidence base” on the short- and long-term health effects — both beneficial and harmful — of cannabis use.

“Our desire is to fill the research void that currently exists in the science of cannabis,” says Broderick, who was an early investor in Canada’s medical marijuana market.

Broderick is the founder of Uji Capital LLC, a family office focused on quantitative opportunities in global equity capital markets. Identifying the growth of the Canadian legal cannabis market as a strategic investment opportunity, Broderick took equity positions in Tweed Marijuana Inc. and Aphria Inc., which have since grown into two of North America’s most successful cannabis companies. Subsequently, Broderick made a private investment in and served as a board member for Tokyo Smoke, a cannabis brand portfolio, which merged in 2017 to create Hiku Brands, where he served as chairman. Hiku Brands was acquired by Canopy Growth Corp. in 2018.

Through the Broderick gifts to Harvard Medical School and MIT’s School of Science through the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory and the McGovern Institute for Brain Research, the Broderick funds will support independent studies of the neurobiology of cannabis; its effects on brain development, various organ systems and overall health, including treatment and therapeutic contexts; and cognitive, behavioral and social ramifications.

“I want to destigmatize the conversation around cannabis — and, in part, that means providing facts to the medical community, as well as the general public,” says Broderick, who argues that independent research needs to form the basis for policy discussions, regardless of whether it is good for business. “Then we’re all working from the same information. We need to replace rhetoric with research.”

MIT: Focused on brain health and function

The gift to MIT from Broderick will provide $4.5 million over three years to support independent research for four scientists at the McGovern and Picower institutes.

Two of these researchers — John Gabrieli, the Grover Hermann Professor of Health Sciences and Technology, a professor of brain and cognitive sciences, and a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research; and Myriam Heiman, the Latham Family Associate Professor of Neuroscience at the Picower Institute — will separately explore the relationship between cannabis and schizophrenia.

Gabrieli, who directs the Martinos Imaging Center at MIT, will monitor any potential therapeutic value of cannabis for adults with schizophrenia using fMRI scans and behavioral studies.

“The ultimate goal is to improve brain health and wellbeing,” says Gabrieli. “And we have to make informed decisions on the way to this goal, wherever the science leads us. We need more data.”

Heiman, who is a molecular neuroscientist, will study how chronic exposure to phytocannabinoid molecules THC and CBD may alter the developmental molecular trajectories of cell types implicated in schizophrenia.

“Our lab’s research may provide insight into why several emerging lines of evidence suggest that adolescent cannabis use can be associated with adverse outcomes not seen in adults,” says Heiman.

In addition to these studies, Gabrieli also hopes to investigate whether cannabis can have therapeutic value for autism spectrum disorders, and Heiman plans to look at whether cannabis can have therapeutic value for Huntington’s disease.

MIT Institute Professor Ann Graybiel has proposed to study the cannabinoid 1 (CB1) receptor, which mediates many of the effects of cannabinoids. Her team recently found that CB1 receptors are tightly linked to dopamine — a neurotransmitter that affects both mood and motivation. Graybiel, who is also a member of the McGovern Institute, will examine how CB1 receptors in the striatum, a deep brain structure implicated in learning and habit formation, may influence dopamine release in the brain. These findings will be important for understanding the effects of cannabis on casual users, as well as its relationship to addictive states and neuropsychiatric disorders.

Earl Miller, Picower Professor of Neuroscience at the Picower Institute, will study effects of cannabinoids on both attention and working memory. His lab has recently formulated a model of working memory and unlocked how anesthetics reduce consciousness, showing in both cases a key role in the brain’s frontal cortex for brain rhythms, or the synchronous firing of neurons. He will observe how these rhythms may be affected by cannabis use — findings that may be able to shed light on tasks like driving where maintenance of attention is especially crucial.

Harvard Medical School: Mobilizing basic scientists and clinicians to solve an acute biomedical challenge

The Broderick gift provides $4.5 million to establish the Charles R. Broderick Phytocannabinoid Research Initiative at Harvard Medical School, funding basic, translational and clinical research across the HMS community to generate fundamental insights about the effects of cannabinoids on brain function, various organ systems, and overall health.

The research initiative will span basic science and clinical disciplines, ranging from neurobiology and immunology to psychiatry and neurology, taking advantage of the combined expertise of some 30 basic scientists and clinicians across the school and its affiliated hospitals.

The epicenter of these research efforts will be the Department of Neurobiology under the leadership of Bruce Bean and Wade Regehr.

“I am excited by Bob’s commitment to cannabinoid science,” says Regehr, professor of neurobiology in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School. “The research efforts enabled by Bob’s vision set the stage for unraveling some of the most confounding mysteries of cannabinoids and their effects on the brain and various organ systems.”

Bean, Regehr, and fellow neurobiologists Rachel Wilson and Bernardo Sabatini, for example, focus on understanding the basic biology of the cannabinoid system, which includes hundreds of plant and synthetic compounds as well as naturally occurring cannabinoids made in the brain.

Cannabinoid compounds activate a variety of brain receptors, and the downstream biological effects of this activation are astoundingly complex, varying by age and sex, and complicated by a person’s physiologic condition and overall health. This complexity and high degree of variability in individual biology has hampered scientific understanding of the positive and negative effects of cannabis on the human body. Bean, Regehr, and colleagues have already made critical insights showing how cannabinoids influence cell-to-cell communication in the brain.

“Even though cannabis products are now widely available, and some used clinically, we still understand remarkably little about how they influence brain function and neuronal circuits in the brain,” says Bean, the Robert Winthrop Professor of Neurobiology in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS. “This gift will allow us to conduct critical research into the neurobiology of cannabinoids, which may ultimately inform new approaches for the treatment of pain, epilepsy, sleep and mood disorders, and more.”

To propel research findings from lab to clinic, basic scientists from HMS will partner with clinicians from Harvard-affiliated hospitals, bringing together clinicians and scientists from disciplines including cardiology, vascular medicine, neurology, and immunology in an effort to glean a deeper and more nuanced understanding of cannabinoids’ effects on various organ systems and the body as a whole, rather than just on isolated organs.

For example, Bean and colleague Gary Yellen, who are studying the mechanisms of action of antiepileptic drugs, have become interested in the effects of cannabinoids on epilepsy, an interest they share with Elizabeth Thiele, director of the pediatric epilepsy program at Massachusetts General Hospital. Thiele is a pioneer in the use of cannabidiol for the treatment of drug-resistant forms of epilepsy. Despite proven clinical efficacy and recent FDA approval for rare childhood epilepsies, researchers still do not know exactly how cannabidiol quiets the misfiring brain cells of patients with the seizure disorder. Understanding its mechanism of action could help in developing new agents for treating other forms of epilepsy and other neurologic disorders.

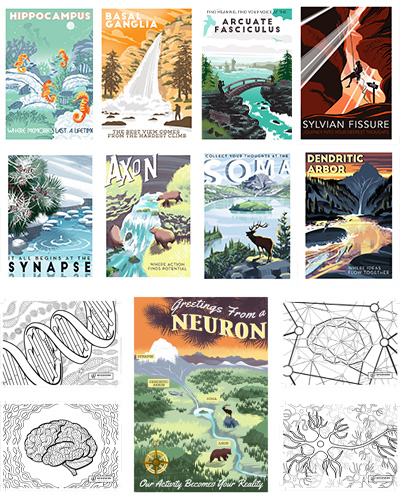

Signals flow through the nervous system from one neuron to the next across synapses.

Signals flow through the nervous system from one neuron to the next across synapses. The axon is the long, thin neural cable that carries electrical impulses called action potentials from the soma to synaptic terminals at downstream neurons.

The axon is the long, thin neural cable that carries electrical impulses called action potentials from the soma to synaptic terminals at downstream neurons. The soma, or cell body, is the control center of the neuron, where the nucleus is located.

The soma, or cell body, is the control center of the neuron, where the nucleus is located. Long branching neuronal processes called dendrites receive synaptic inputs from thousands of other neurons and carry those signals to the cell body.

Long branching neuronal processes called dendrites receive synaptic inputs from thousands of other neurons and carry those signals to the cell body.