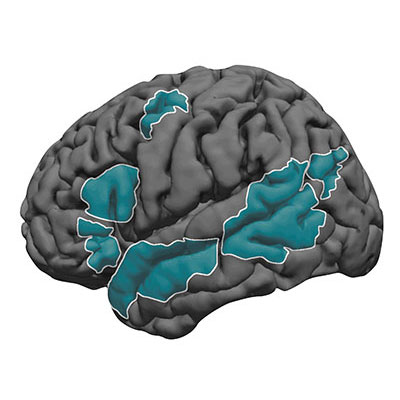

Over several decades, neuroscientists have created a well-defined map of the brain’s “language network,” or the regions of the brain that are specialized for processing language. Found primarily in the left hemisphere, this network includes regions within Broca’s area, as well as in other parts of the frontal and temporal lobes.

However, the vast majority of those mapping studies have been done in English speakers as they listened to or read English texts. MIT neuroscientists have now performed brain imaging studies of speakers of 45 different languages. The results show that the speakers’ language networks appear to be essentially the same as those of native English speakers.

The findings, while not surprising, establish that the location and key properties of the language network appear to be universal. The work also lays the groundwork for future studies of linguistic elements that would be difficult or impossible to study in English speakers because English doesn’t have those features.

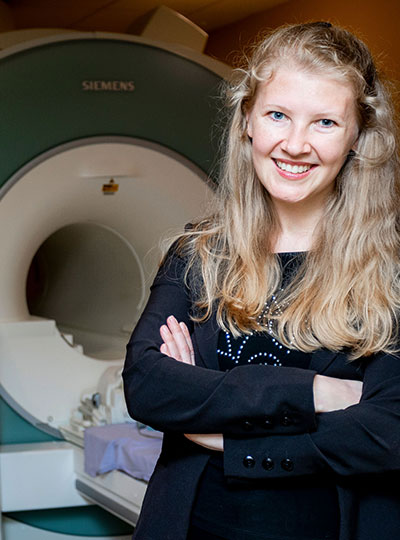

“This study is very foundational, extending some findings from English to a broad range of languages,” says Evelina Fedorenko, the Frederick A. and Carole J. Middleton Career Development Associate Professor of Neuroscience at MIT and a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research. “The hope is that now that we see that the basic properties seem to be general across languages, we can ask about potential differences between languages and language families in how they are implemented in the brain, and we can study phenomena that don’t really exist in English.”

Fedorenko is the senior author of the study, which appears today in Nature Neuroscience. Saima Malik-Moraleda, a PhD student in the Speech and Hearing Bioscience and Technology program at Harvard University, and Dima Ayyash, a former research assistant, are the lead authors of the paper.

Mapping language networks

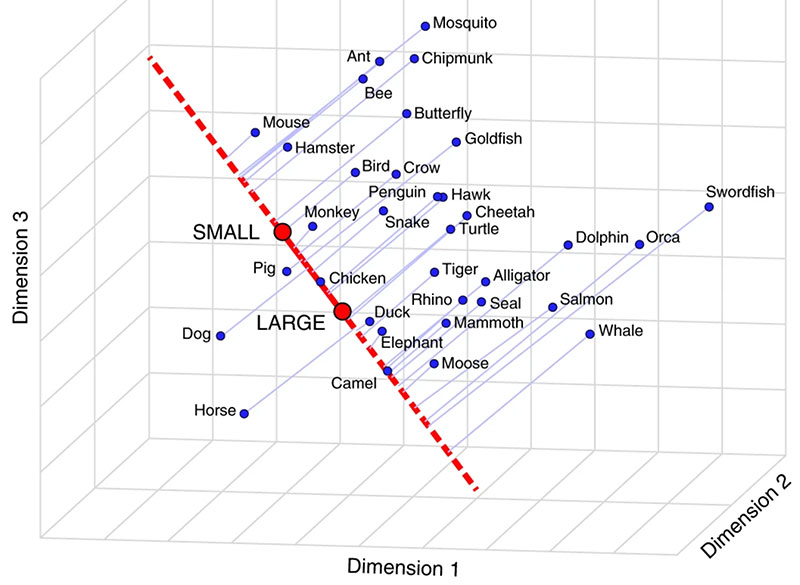

The precise locations and shapes of language areas differ across individuals, so to find the language network, researchers ask each person to perform a language task while scanning their brains with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Listening to or reading sentences in one’s native language should activate the language network. To distinguish this network from other brain regions, researchers also ask participants to perform tasks that should not activate it, such as listening to an unfamiliar language or solving math problems.

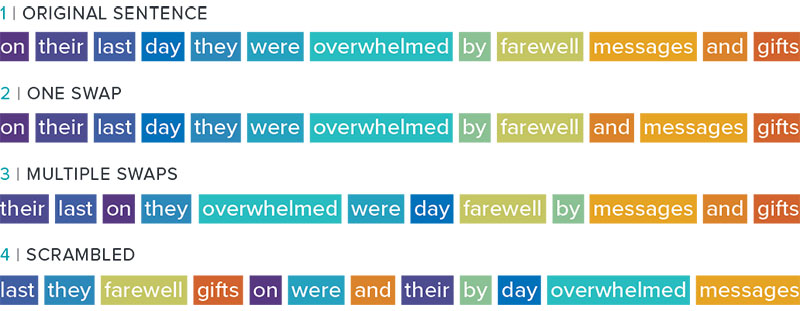

Several years ago, Fedorenko began designing these “localizer” tasks for speakers of languages other than English. While most studies of the language network have used English speakers as subjects, English does not include many features commonly seen in other languages. For example, in English, word order tends to be fixed, while in other languages there is more flexibility in how words are ordered. Many of those languages instead use the addition of morphemes, or segments of words, to convey additional meaning and relationships between words.

“There has been growing awareness for many years of the need to look at more languages, if you want make claims about how language works, as opposed to how English works,” Fedorenko says. “We thought it would be useful to develop tools to allow people to rigorously study language processing in the brain in other parts of the world. There’s now access to brain imaging technologies in many countries, but the basic paradigms that you would need to find the language-responsive areas in a person are just not there.”

For the new study, the researchers performed brain imaging of two speakers of 45 different languages, representing 12 different language families. Their goal was to see if key properties of the language network, such as location, left lateralization, and selectivity, were the same in those participants as in people whose native language is English.

The researchers decided to use “Alice in Wonderland” as the text that everyone would listen to, because it is one of the most widely translated works of fiction in the world. They selected 24 short passages and three long passages, each of which was recorded by a native speaker of the language. Each participant also heard nonsensical passages, which should not activate the language network, and was asked to do a variety of other cognitive tasks that should not activate it.

The team found that the language networks of participants in this study were found in approximately the same brain regions, and had the same selectivity, as those of native speakers of English.

“Language areas are selective,” Malik-Moraleda says. “They shouldn’t be responding during other tasks such as a spatial working memory task, and that was what we found across the speakers of 45 languages that we tested.”

Additionally, language regions that are typically activated together in English speakers, such as the frontal language areas and temporal language areas, were similarly synchronized in speakers of other languages.

The researchers also showed that among all of the subjects, the small amount of variation they saw between individuals who speak different languages was the same as the amount of variation that would typically be seen between native English speakers.

Similarities and differences

While the findings suggest that the overall architecture of the language network is similar across speakers of different languages, that doesn’t mean that there are no differences at all, Fedorenko says. As one example, researchers could now look for differences in speakers of languages that predominantly use morphemes, rather than word order, to help determine the meaning of a sentence.

“There are all sorts of interesting questions you can ask about morphological processing that don’t really make sense to ask in English, because it has much less morphology,” Fedorenko says.

Another possibility is studying whether speakers of languages that use differences in tone to convey different word meanings would have a language network with stronger links to auditory brain regions that encode pitch.

Right now, Fedorenko’s lab is working on a study in which they are comparing the ‘temporal receptive fields’ of speakers of six typologically different languages, including Turkish, Mandarin, and Finnish. The temporal receptive field is a measure of how many words the language processing system can handle at a time, and for English, it has been shown to be six to eight words long.

“The language system seems to be working on chunks of just a few words long, and we’re trying to see if this constraint is universal across these other languages that we’re testing,” Fedorenko says.

The researchers are also working on creating language localizer tasks and finding study participants representing additional languages beyond the 45 from this study.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and research funds from MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, the McGovern Institute, and the Simons Center for the Social Brain. Malik-Moraleda was funded by a la Caixa Fellowship and a Friends of McGovern fellowship.