This story also appears in the Fall 2025 issue of BrainScan.

___

The question of how we know ourselves might seem the subject of philosophers, but it is just as much a matter of biology. As modern neuroscientists obtain an increasingly sophisticated understanding of how the brain generates emotions, responds to the external world, and learns from experience, some researchers are returning to a central question: How do we know our experiences, emotions, and physical sensations belong to us?

Curiosity about how the brain generates our sense of self has been a driving force for the research of McGovern Investigator Fan Wang. Following that curiosity has drawn Wang into diverse studies, exploring the origins of pain and the mechanisms we use to control our movements.

“We cannot pinpoint a set of active neurons and say that’s the sense of self. That still remains a mystery,” says Wang, who is also a professor of brain and cognitive sciences and co-director of the K. Lisa Yang and Hock E. Tan Center for Molecular Therapeutics at MIT. But she and other neuroscientists are drilling down into different functions of the brain that together might generate our awareness of ourselves.

Wang, who teaches the undergraduate course, “Neurobiology of Self,” explains that there are lots of ways to think about our sense of self, which are probably deeply integrated in the brain. Some are mostly about our physical bodies: How do we experience touch? How do we understand

where we are in space, or recognize the boundary between ourselves and rest of the world? Some consider more internal sensations, like how we experience pain or hunger. Emotion is also key to our sense of self: How do we know that anger or joy are our own, and why do these states change the way our bodies feel?

Wang can trace her initial interest in the brain’s sense of self to work she did as a graduate student in Richard Axel’s lab at Columbia University. The lab had identified receptors expressed by sensory neurons in the nose that detect odorous substances. Wang and others discovered the pathways that information about these smells takes to the brain, and how the brain distinguishes one smell from another.

Who is the “knower” of this information? “The answer,” Wang says, “is ‘I’ or ‘me.’ But understanding where I get the sense of self and how that is constructed, is what drives me to do neuroscience.”

Mechanisms of movement

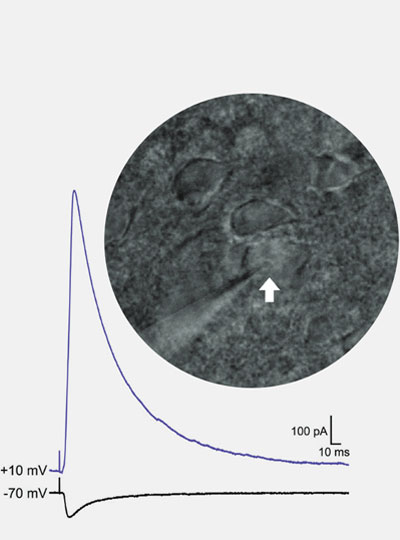

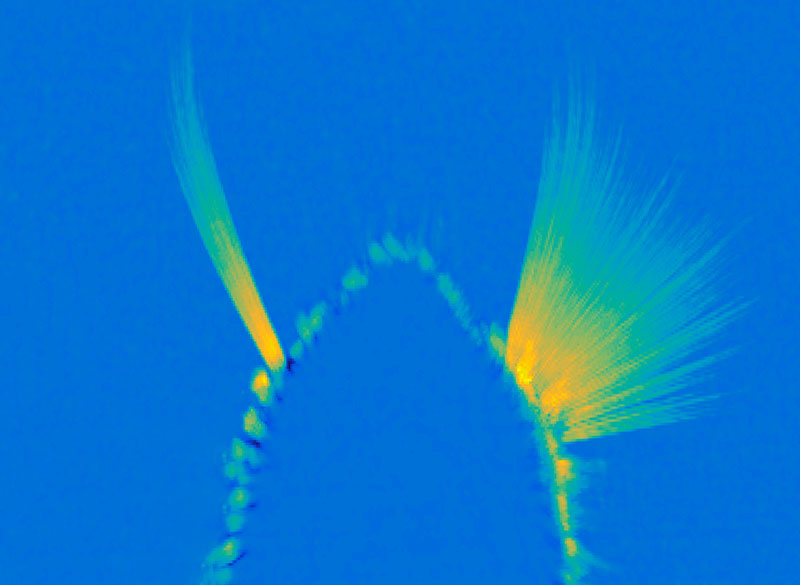

In her lab at the McGovern Institute, Wang is studying how the brain controls the body’s movements, which she sees as closely tied to the awareness of our physical selves. “The reason I think I am in my body is because I can control my movement. I generate the movement. I cannot control your movement,” says Wang. “Volitional movement gives us a sense of agency, and this sense of agency resembles the sense of self.” For the mice that the group studies, one crucial type of movement comes from the whiskers, which the animals depend on as they explore their environments. Wang’s group has traced the neural circuity that controls whiskers’ rhythmic back-and-forth, which is initiated in the brainstem, where many of the body’s most vital functions are controlled. Wang describes the simple circuit as an oscillator, or a self-generated loop.

Once it’s started, “the movement can go on unless some other signals stop it,” she says. The movement the circuit generates is simple but voluntary, and can be fine-tuned based on the sensory feedback the whiskers relay back to the brain. They’ve also been investigating how mice move the larynx to generate the squeaks and calls they use to communicate. These intentional movements must be coordinated with the ongoing cycles of respiration since we produce normal sounds only during expiration. Wang’s team has found neurons in the brainstem that generate vocalization-specific movements, and also discovered how respiration-controlling neural circuits can override them, ensuring that breathing is prioritized.

Wang says understanding the circuitry that controls these simple movements sets the stage for figuring out how the brain modifies activity in those circuits to create more complex, intentional movements. “That brings me closer to understanding where this volition is generated — and closer to this sense of self,” she says.

Emotional pain

Still, she knows that volitional movements — even those generated in response to perceptions of the environment — do not, on their own, define a sense of self. As a counterexample, she looks to self-driving cars: “There’s sensory information coming into the central computer, which then generates a motor output — where to drive, where to turn, where to stop. But none of us think a Waymo taxi has a sense of self.”

Wang says when she pondered the ways in which AI-powered cars lack a sense of self, she began thinking about emotions and pain. “If the self-driving Waymo crashes, it will not feel pain,” she says. “But if we hurt ourselves, we will feel pain. And we will hate that, and then we’ll learn.” So her lab is also exploring how the nervous system generates pain perception, including the emotional response that it evokes.

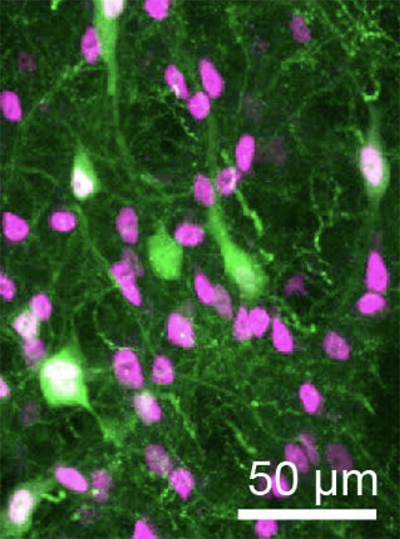

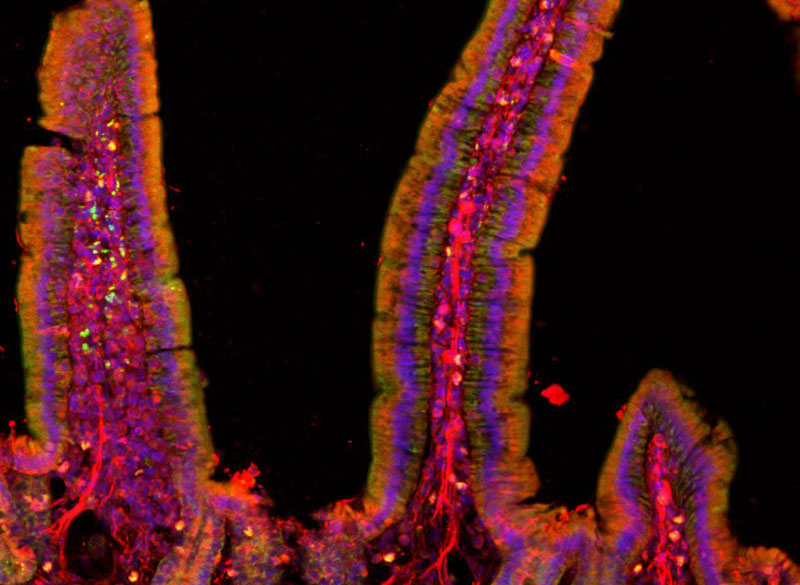

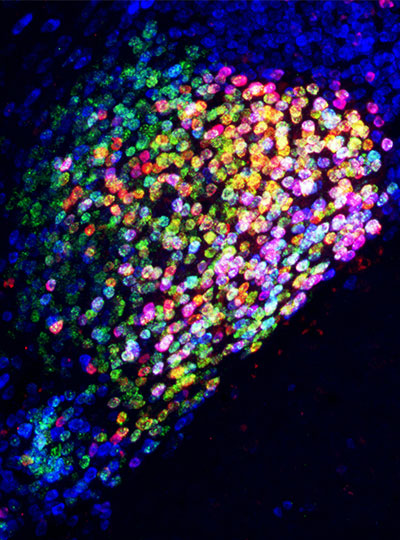

In both humans and mice, pain causes emotional suffering that can be recognized and measured through changes in body functions like heart rate and blood pressure. With funding from the K. Lisa Yang Brain-Body Center at MIT, Wang’s lab is carefully tracking these involuntary, or autonomic, functions to gain a more complete understanding of pain’s emotional impact. This approach has helped clarify the role of pain-suppressing neurons in the brain’s amygdala — an important emotion-processing center — that Wang’s team discovered in 2020. When researchers selectively activate those cells in mice, the animals’ behavior makes it clear that the neurons are suppressing pain. Now, the group has learned that activating these neurons suppresses the autonomic response to pain.

Wang says there’s hope that modulating pain’s emotional response might be a way to treat chronic pain in patients. She explains that some patients with damage to another one of the brain’s emotional centers, the cingulate cortex, feel painful stimuli, but experience them as merely intense sensations. That suggests that it might be possible to modulate the emotional response to pain to eliminate patients’ suffering, without blocking the protective information that pain can provide.

The team has also been focusing on another set of anesthesia-activated neurons, which they have found suppress anxiety. When anxiety-suppressing neurons are activated in mice, the animals’ heart rates slow and they become more willing to explore bright, open spaces. Another anxiety-associated measure — heart rate variability — increases. Wang explains that this change is particularly significant: “If you have persistent low heart rate variability, especially in veterans, that is a very good predictor for anxiety developing into depression in the future,” she says.

The team’s findings, which suggest that changes in autonomic functions may themselves relieve anxiety, point toward potential new targets for anti-anxiety therapies. And by highlighting the connection between emotion and bodily responses, they offer more clues about our sense of self. “These neurons are now changing some high-level concept about anxiety,” Wang points out.

That link between emotion and body seems to Wang to be key to the sense of self. The big questions remain unanswered, but that simply stokes her curiosity. “I can be aware of my bodily responses: I am aware of ‘I am anxious’ or ‘I am in pain.’ I can see the pathways from which stimuli go into these nervous systems and come back down to the body and control the response. But I still don’t know who is the person — the knower,” she says. “I haven’t found it, so I’m going to keep looking.”