A sense of timing

Behavioral experiments, brain recordings and computer models are all helping to explain how the brain processes time.

The ability to measure time and to control the timing of actions is critical for almost every aspect of behavior. Yet the mechanisms by which our brains process time are still largely mysterious.

We experience time on many different scales—from milliseconds to years— but of particular interest is the middle range, the scale of seconds over which we perceive time directly, and over which many of our actions and thoughts unfold.

“We speak of a sense of time, yet unlike our other senses there is no sensory organ for time,” says McGovern Investigator Mehrdad Jazayeri. “It seems to come entirely from within. So if we understand time, we should be getting close to understanding mental processes.”

Singing in the brain

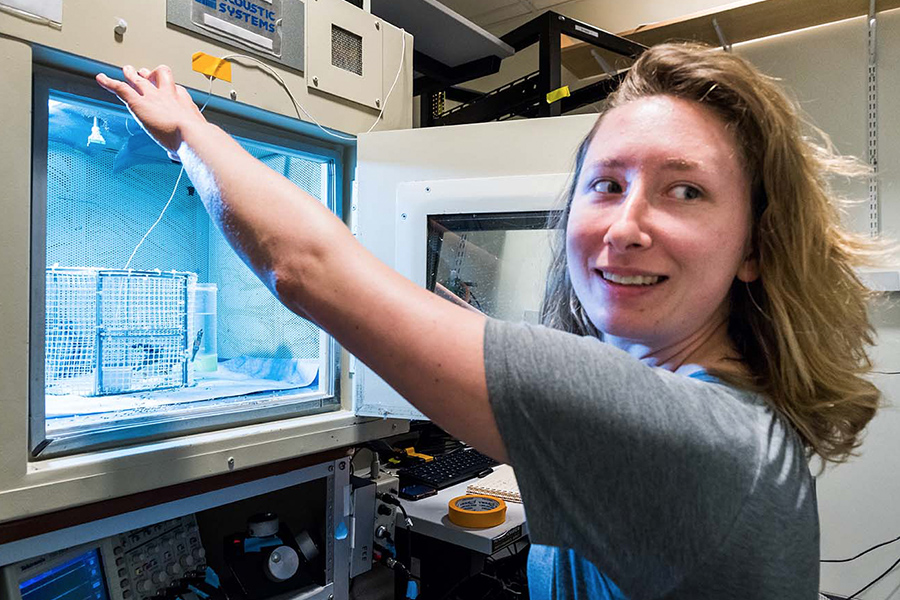

Emily Mackevicius comes to work in the early morning because that’s when her birds are most likely to sing. A graduate student in the lab of McGovern Investigator Michale Fee, she is studying zebra finches, songbirds that learn to sing by copying their fathers. Bird song involves a complex and precisely timed set of movements, and Mackevicius, who plays the cello in her spare time, likens it to musical performance. “With every phrase, you have to learn a sequence of finger movements and bowing movements, and put it all together with exact timing. The birds are doing something very similar with their vocal muscles.”

A typical zebra finch song lasts about one second, and consists of several syllables, produced at a rate similar to the syllables in human speech. Each song syllable involves a precisely timed sequence of muscle commands, and understanding how the bird’s brain generates this sequence is a central goal for Fee’s lab. Birds learn it naturally without any need for training, making it an ideal model for understanding the complex action sequences that represent the fundamental “building blocks” of behavior.

Some years ago Fee and colleagues made a surprising discovery that has shaped their thinking ever since. Within a part of the bird brain called HVC, they found neurons that fire a single short burst of pulses at exactly the same point on every repetition of the song. Each burst lasts about a hundredth of a second, and different neurons fire at different times within the song. With about 20,000 neurons in HVC, it was easy to imagine that there would be specific neurons active at every point in the song, meaning that each time point could be represented by the activity of a handful of individual neurons.

Proving this was not easy—“we had to wait about ten years for the technology to catch up,” says Fee—but they finally succeeded last year, when students Tatsuo Okubo and Galen Lynch analyzed recordings from hundreds of individual HVC neurons, and found that they do indeed fire in a fixed sequence, covering the entire song period.

“We think it’s like a row of falling dominoes,” says Fee. “The neurons are connected to each other so that when one fires it triggers the next one in the chain.” It’s an appealing model, because it’s easy to see how a chain of activity could control complex action sequences, simply by connecting individual time-stamp neurons to downstream motor neurons. With the correct connections, each movement is triggered at the right time in the sequence. Fee believes these motor connections are learned through trial and error—like babies babbling as they learn to speak—and a separate project in his lab aims to understand how this learning occurs.

But the domino metaphor also begs another question: who sets up the dominoes in the first place? Mackevicius and Okubo, along with summer student Hannah Payne, set out to answer this question, asking how HVC becomes wired to produce these precisely timed chain reactions.

Mackevicius, who studied math as an undergraduate before turning to neuroscience, developed computer simulations of the HVC neuronal network, and Okubo ran experiments to test the predictions, recording from young birds at different stages in the learning process. “We found that setting up a chain is surprisingly easy,” says Mackevicius. “If we start with a randomly connected network, and some realistic assumptions about the “plasticity rules” by which synapses change with repeated use, we found that these chains emerge spontaneously. All you need is to give them a push—like knocking over the first domino.”

Their results also suggested how a young bird learns to produce different syllables, as it progresses from repetitive babbling to a more adult-like song. “At first, there’s just one big burst of neural activity, but as the song becomes more complex, the activity gradually spreads out in time and splits into different sequences, each controlling a different syllable. It’s as if you started with lots of dominos all clumped together, and then gradually they become sorted into different rows.”

Does something similar happen in the human brain? “It seems very likely,” says Fee. “Many of our movements are precisely timed—think about speaking a sentence or performing a musical instrument or delivering a tennis serve. Even our thoughts often happen in sequences. Things happen faster in birds than mammals, but we suspect the underlying mechanisms will be very similar.”

Speed control

One floor above the Fee lab, Mehrdad Jazayeri is also studying how time controls actions, using humans and monkeys rather than birds. Like Fee, Jazayeri comes from an engineering background, and his goal is to understand, with an engineer’s level of detail, how we perceive time and use it flexibly to control our actions.

To begin to answer this question, Jazayeri trained monkeys to remember time intervals of a few seconds or less, and to reproduce them by pressing a button or making an eye movement at the correct time after a visual cue appears on a screen. He then recorded brain activity as the monkeys perform this task, to find out how the brain measures elapsed time. “There were two prominent ideas in the field,” he explains. “One idea was that there is an internal clock, and that the brain can somehow count the accumulating ticks. Another class of models had proposed that there are multiple oscillators that come in and out of phase at different times.”

When they examined the recordings, however, the results did not fit either model. Despite searching across multiple brain areas, Jazayeri and his colleagues found no sign of ticking or oscillations. Instead, their recordings revealed complex patterns of activity, distributed across populations of neurons; moreover, as the monkey produced longer or shorter intervals, these activity patterns were stretched or compressed in time, to fit the overall duration of each interval. In other words, says Jazayeri, the brain circuits were able to adjust the speed with which neural signals evolve over time. He compares it to a group of musicians performing a complex piece of music. “Each player has their own part, which they can play faster or slower depending on the overall tempo of the music.”

Ready-set-go

Jazayeri is also using time as a window onto a broader question—how our perceptions and decisions are shaped by past experience. “It’s one of the great questions in neuroscience, but it’s not easy to study. One of the great advantages of studying timing is that it’s easy to measure precisely, so we can frame our questions in precise mathematical ways.”

The starting point for this work was a deceptively simple task, which Jazayeri calls “Ready-Set-Go.” In this task, the subject is given the first two beats of a regular rhythm (“Ready, Set”) and must then generate the third beat (“Go”) at the correct time. To perform this task, the brain must measure the duration between Ready and Set and then immediately reproduce it.

Humans can do this fairly accurately, but not perfectly—their response times are imprecise, presumably because there is some “noise” in the neural signals that convey timing information within the brain. In the face of this uncertainty, the optimal strategy (known mathematically as Bayesian Inference) is to bias the time estimates based on prior expectations, and this is exactly what happened in Jazayeri’s experiments. If the intervals in previous trials were shorter, then people tend to under-estimate the next interval, whereas if the previous intervals were longer, they will over-estimate. In other words, people use their memory to improve their time estimates.

Monkeys can also learn this task and show similar biases, providing an opportunity to study how the brain establishes and stores these prior expectations, and how these expectations influence subsequent behavior. Again, Jazayeri and colleagues recorded from large numbers of neurons during the task. These patterns are complex and not easily described in words, but in mathematical terms, the activity forms a geometric structure known as a manifold. “Think of it as a curved surface, analogous to a cylinder,” he says. “In the past, people could not see it because they could only record from one or a few neurons at a time. We have to measure activity across large numbers of neurons simultaneously if we want to understand the workings of the system.”

Computing time

To interpret their data, Jazayeri and his team often turn to computer models based on artificial neural networks. “These models are a powerful tool in our work because we can fully reverse-engineer them and gain insight into the underlying mechanisms,” he explains. His lab has now succeeded in training a recurrent neural network that can perform the Ready-Set-Go task, and they have found that the model develops a manifold similar to the real brain data. This has led to the intriguing conjecture that memory of past experiences can be embedded in the structure of the manifold.

Jazayeri concludes: “We haven’t connected all the dots, but I suspect that many questions about brain and behavior will find their answers in the geometry and dynamics of neural activity.” Jazayeri’s long-term ambition is to develop predictive models of brain function. As an analogy, he says, think of a pendulum. “If we know its current state—its position and speed—we can predict with complete confidence what it will do next, and how it will respond to a perturbation. We don’t have anything like that for the brain—nobody has been able to do that, not even the simplest brain functions. But that’s where we’d eventually like to be.”

A clock within the brain?

It is not yet clear how the mechanisms studied by Fee and Jazayeri are related. “We talk together often, but we are still guessing how the pieces fit together,” says Fee. But one thing they both agree on is the lack of evidence for any central clock within the brain. “Most people have this intuitive feeling that time is a unitary thing, and that there must be some central clock inside our head, coordinating everything like the conductor of the orchestra or the clock inside your computer,” says Jazayeri. “Even many experts in the field believe this, but we don’t think it’s right.” Rather, his work and Fee’s both point to the existence of separate circuits for different time-related behaviors, such as singing. If there is no clock, how do the different systems work together to create our apparently seamless perception of time? “It’s still a big mystery,” says Jazayeri. “Questions like that are what make neuroscience so interesting.”