Electrical properties of dendrites help explain our brain’s unique computing power

Neurons in human and rat brains carry electrical signals in different ways, scientists find.

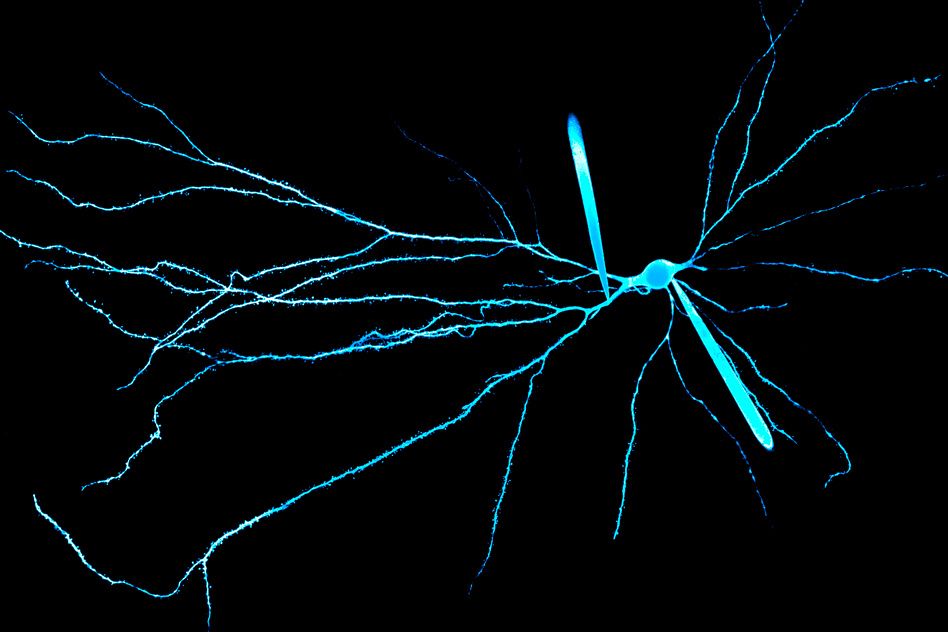

Neurons in the human brain receive electrical signals from thousands of other cells, and long neural extensions called dendrites play a critical role in incorporating all of that information so the cells can respond appropriately.

Using hard-to-obtain samples of human brain tissue, MIT neuroscientists have now discovered that human dendrites have different electrical properties from those of other species. Their studies reveal that electrical signals weaken more as they flow along human dendrites, resulting in a higher degree of electrical compartmentalization, meaning that small sections of dendrites can behave independently from the rest of the neuron.

These differences may contribute to the enhanced computing power of the human brain, the researchers say.

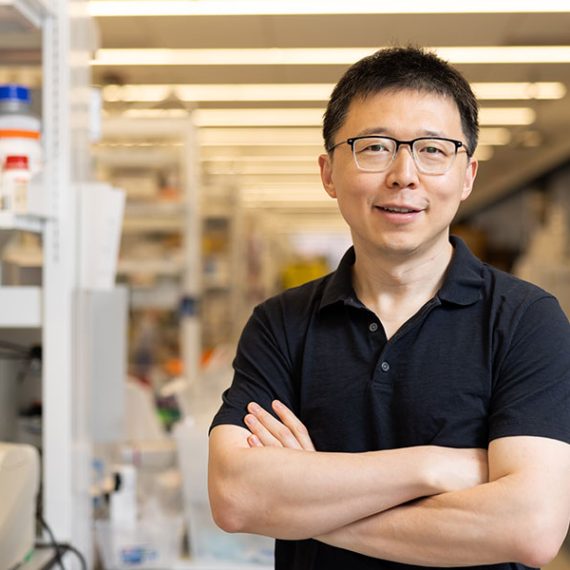

“It’s not just that humans are smart because we have more neurons and a larger cortex. From the bottom up, neurons behave differently,” says Mark Harnett, the Fred and Carole Middleton Career Development Assistant Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences. “In human neurons, there is more electrical compartmentalization, and that allows these units to be a little bit more independent, potentially leading to increased computational capabilities of single neurons.”

Harnett, who is also a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research, and Sydney Cash, an assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, are the senior authors of the study, which appears in the Oct. 18 issue of Cell. The paper’s lead author is Lou Beaulieu-Laroche, a graduate student in MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences.

Neural computation

Dendrites can be thought of as analogous to transistors in a computer, performing simple operations using electrical signals. Dendrites receive input from many other neurons and carry those signals to the cell body. If stimulated enough, a neuron fires an action potential — an electrical impulse that then stimulates other neurons. Large networks of these neurons communicate with each other to generate thoughts and behavior.

The structure of a single neuron often resembles a tree, with many branches bringing in information that arrives far from the cell body. Previous research has found that the strength of electrical signals arriving at the cell body depends, in part, on how far they travel along the dendrite to get there. As the signals propagate, they become weaker, so a signal that arrives far from the cell body has less of an impact than one that arrives near the cell body.

Dendrites in the cortex of the human brain are much longer than those in rats and most other species, because the human cortex has evolved to be much thicker than that of other species. In humans, the cortex makes up about 75 percent of the total brain volume, compared to about 30 percent in the rat brain.

Although the human cortex is two to three times thicker than that of rats, it maintains the same overall organization, consisting of six distinctive layers of neurons. Neurons from layer 5 have dendrites long enough to reach all the way to layer 1, meaning that human dendrites have had to elongate as the human brain has evolved, and electrical signals have to travel that much farther.

In the new study, the MIT team wanted to investigate how these length differences might affect dendrites’ electrical properties. They were able to compare electrical activity in rat and human dendrites, using small pieces of brain tissue removed from epilepsy patients undergoing surgical removal of part of the temporal lobe. In order to reach the diseased part of the brain, surgeons also have to take out a small chunk of the anterior temporal lobe.

With the help of MGH collaborators Cash, Matthew Frosch, Ziv Williams, and Emad Eskandar, Harnett’s lab was able to obtain samples of the anterior temporal lobe, each about the size of a fingernail.

Evidence suggests that the anterior temporal lobe is not affected by epilepsy, and the tissue appears normal when examined with neuropathological techniques, Harnett says. This part of the brain appears to be involved in a variety of functions, including language and visual processing, but is not critical to any one function; patients are able to function normally after it is removed.

Once the tissue was removed, the researchers placed it in a solution very similar to cerebrospinal fluid, with oxygen flowing through it. This allowed them to keep the tissue alive for up to 48 hours. During that time, they used a technique known as patch-clamp electrophysiology to measure how electrical signals travel along dendrites of pyramidal neurons, which are the most common type of excitatory neurons in the cortex.

These experiments were performed primarily by Beaulieu-Laroche. Harnett’s lab (and others) have previously done this kind of experiment in rodent dendrites, but his team is the first to analyze electrical properties of human dendrites.

Unique features

The researchers found that because human dendrites cover longer distances, a signal flowing along a human dendrite from layer 1 to the cell body in layer 5 is much weaker when it arrives than a signal flowing along a rat dendrite from layer 1 to layer 5.

They also showed that human and rat dendrites have the same number of ion channels, which regulate the current flow, but these channels occur at a lower density in human dendrites as a result of the dendrite elongation. They also developed a detailed biophysical model that shows that this density change can account for some of the differences in electrical activity seen between human and rat dendrites, Harnett says.

Nelson Spruston, senior director of scientific programs at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Janelia Research Campus, described the researchers’ analysis of human dendrites as “a remarkable accomplishment.”

“These are the most carefully detailed measurements to date of the physiological properties of human neurons,” says Spruston, who was not involved in the research. “These kinds of experiments are very technically demanding, even in mice and rats, so from a technical perspective, it’s pretty amazing that they’ve done this in humans.”

The question remains, how do these differences affect human brainpower? Harnett’s hypothesis is that because of these differences, which allow more regions of a dendrite to influence the strength of an incoming signal, individual neurons can perform more complex computations on the information.

“If you have a cortical column that has a chunk of human or rodent cortex, you’re going to be able to accomplish more computations faster with the human architecture versus the rodent architecture,” he says.

There are many other differences between human neurons and those of other species, Harnett adds, making it difficult to tease out the effects of dendritic electrical properties. In future studies, he hopes to explore further the precise impact of these electrical properties, and how they interact with other unique features of human neurons to produce more computing power.

The research was funded by the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Dana Foundation David Mahoney Neuroimaging Grant Program, and the National Institutes of Health.