Investigating the embattled brain

Combat veteran and McGovern graduate student Omar Rutledge drives research on PTSD.

As an Iraq war veteran, Omar Rutledge is deeply familiar with post-traumatic stress – recurring thoughts and memories that persist long after a danger has passed – and he knows that a brain altered by trauma is not easily fixed. But as a graduate student in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Rutledge is determined to change that. He wants to understand exactly how trauma alters the brain – and whether the tools of neuroscience can be used to help fellow veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) heal from their experiences.

“In the world of PTSD research, I look to my left and to my right, and I don’t see other veterans, certainly not former infantrymen,” says Rutledge, who served in the US Army and was deployed to Iraq from March 2003 to July 2004. “If there are so few of us in this space, I feel like I have an obligation to make a difference for all who suffer from the traumatic experiences of war.”

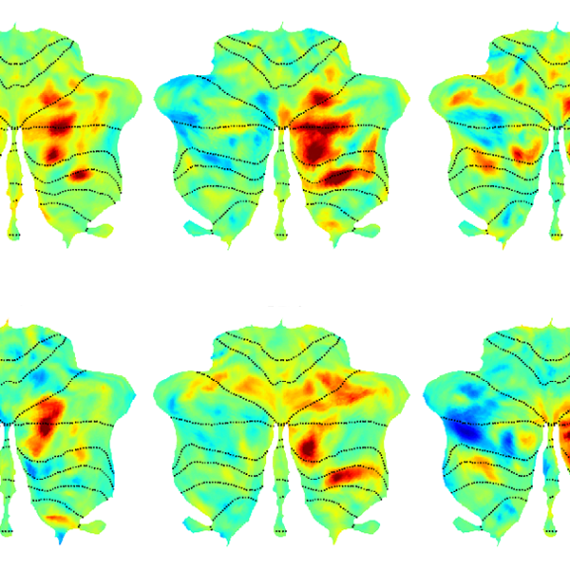

Rutledge is uniquely positioned to make such a difference in the lab of McGovern Investigator John Gabrieli, where researchers use technologies like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electroencephalography (EEG), and magnetoencephalography (MEG) to peer into the human brain and explore how it powers our thoughts, memories, and emotions. Rutledge is studying how PTSD weakens the connection between the amygdala, which is responsible for emotions like fear, and the prefrontal cortex, which regulates or controls these emotional responses. He hopes these studies will eventually lead to the development of wearable technologies that can retrain the brain to be less responsive to triggering events.

“I feel like it has been a mission of mine to do this kind of work.”

Though Covid-19 has unexpectedly paused some aspects of his research, Rutledge is pursuing another line of research inspired both by the mandatory social distancing protocols imposed during the lockdown and his own experiences with social isolation. Does chronic social isolation cause physical or chemical changes in the brain similar to those seen in PTSD? And does loneliness exacerbate symptoms of PTSD?

“There’s this hypervigilance that occurs in loneliness, and there’s also something very similar that occurs in PTSD — a heightened awareness of potential threats,” says Rutledge, who is the recipient of Michael Ferrara Graduate Fellowship provided by the Poitras Center, a fellowship made possible by the many friends and family of Michael Ferrara. “The combination of the two may lead to more adverse reactions in people with PTSD.”

In the future, Rutledge hopes to explore whether chronic loneliness impairs reasoning and logic skills and has a deeper impact on veterans who have PTSD.

Although his research tends to resurface painful memories of his own combat experiences, Rutledge says if it can help other veterans heal, it’s worth it. “In the process, it makes me a little bit stronger as well,” he adds.