Why do we dream?

Dreaming is influenced by the consolidation of memories during sleep.

As part of our Ask the Brain series, science writer Shafaq Zia answers the question, “Why do we dream?”

_____

One night, Albert Einstein dreamt that he was walking through a farm where he found a herd of cows against an electric fence. When the farmer switched on the fence, the cows suddenly jumped back, all at the same time. But to the farmer’s eyes, who was standing at the other end of the field, they seemed to have jumped one after another, in a wave formation. Einstein woke up and the Theory of Relativity was born.

Dreaming is one of the oldest biological phenomena; for as long as humans have slept, they’ve dreamt. But through most of our history, dreams have remained mystified, leaving scientists, philosophers, and artists alike searching for meaning.

In many aboriginal cultures, such as the Esa Eja community in Peruvian Amazon, dreaming is a sacred practice for gaining knowledge, or solving a problem, through the dream narrative. But in the last century or so, technological advancements have allowed neuroscientists to take up dreams as a matter of scientific inquiry in order to answer a much-pondered question — what is the purpose of dreaming?

Falling asleep

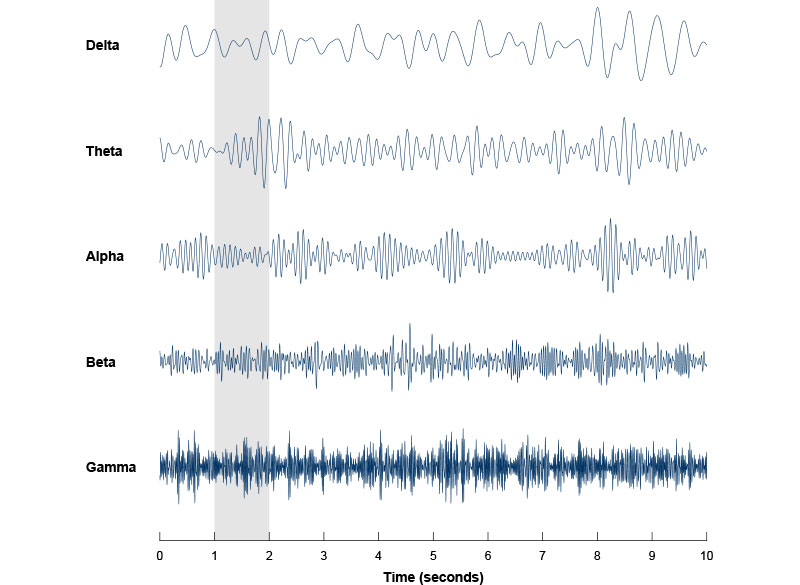

The human brain is a fascinating place. It is composed of approximately 80 billion neurons and it is their combined electrical chatter that generates oscillations known as brain waves. There are five types of brain waves — alpha, beta, theta, delta, and gamma — that each indicate a different state between sleep and wakefulness.

Using EEG, a test that records electrical activity in the brain, scientists have identified that when we’re awake, our brain emits beta and gamma waves. These tend to have a stimulating effect and help us remain actively engaged in mental activities.

But during the transition to sleep, the number of beta waves lowers significantly and the brain produces high levels of alpha waves. These waves regulate attention and help filter out distractions. A recent study led by McGovern Institute Director Robert Desimone, showed that people can actually enhance their attention by controlling their own alpha brain waves using neurofeedback training. It’s unknown how long these effects might last and whether this kind of control could be achieved with other types of brain waves, but the researchers are now planning additional studies to explore these questions.

Alpha waves are also produced when we daydream, meditate, or listen to the sound of rain. As our minds wander, many parts of the brain are engaged, including a specialized system called the “default mode network.” Disturbances in this network, explains Susan Whitfield-Gabrieli, a professor of psychology at Northeastern University and a McGovern Institute research affiliate, have been linked to various brain disorders including schizophrenia, depression and ADHD. By identifying the brain circuits associated with mind wandering, she says, we can begin to develop better treatment options for people suffering from these disorders.

Finally, as we enter a dreamlike state, the prefrontal cortex of the brain, responsible for keeping impulses in check, slowly grows less active. This is when there’s a spur in theta waves that leads to an unconstrained window of consciousness; there is little censorship from the mind, allowing for visceral dreams and creative thoughts.

The dreaming brain

“Every time you learn something, it happens so quickly,” said Dheeraj Roy, postdoctoral fellow in Guoping Feng’s lab at the McGovern Institute. “The brain is continuously recording information, but how do you take a break and then make sense of it all?”

This is where dreams come in, says Roy. During sleep, newly-formed memories are gradually stabilized into a more permanent form of long-term storage in the brain. Dreaming, he says, is influenced by the consolidation of these memories during sleep. Most dreams are made up of experiences, thoughts, emotion, places, and people we have already encountered in our lives. But, during dreaming, bits and pieces of these memories seem to be reorganized to create a particularly bizarre scenario: you’re talking to your sister when it suddenly begins to rain roses and you’re dancing at a New Year’s party.

This re-organization may not be so random; as the brain is processing memories, it pulls together the ones that are seemingly related to each other. Perhaps you dreamt of your sister because you were at a store recently where a candle smelt like her rose-scented perfume, which reminded you of the time you made a new year resolution to spend less money on flowers.

Some brain disorders, like Parkinson’s disease, have been associated with vivid, unpleasant dreams and erratic brain wave patterns. Researchers at the McGovern Institute hope that a better understanding of mechanics of the brain – including neural circuits and brain waves – will help people with Parkinson’s and other brain disorders.

So perhaps dreams aren’t instilled with meaning, symbolism, and wisdom in the way we’ve always imagined, and they simply reflect important biological processes taking place in our brain. But with all that science has uncovered about dreaming and the ways in which it links to creativity and memory, the magical essence of this universal human experience remains untainted.

_____

Do you have a question for The Brain? Ask it here.