Tuning the mind to benefit mental health

As researchers find mounting evidence that mindfulness benefits mental health, McGovern scientists develop and test tools to help young people with the practice.

This story also appears in the Winter 2024 issue of BrainScan.

___

center of this crisis.

Psychiatrists and pediatricians have sounded an alarm. The mental health of youth in the United States is worsening. Youth visits to emergency departments related to depression, anxiety, and behavioral challenges have been on the rise for years. Suicide rates among young people have escalated, too. Researchers have tracked these trends for more than a decade, and the Covid-19 pandemic only exacerbated the situation.

“It’s all over the news, how shockingly common mental health difficulties are,” says John Gabrieli, the Grover Hermann Professor of Health Sciences and Technology at MIT and an investigator at the McGovern Institute. “It’s worsening by every measure.”

Experts worry that our mental health systems are inadequate to meet the growing need. “This has gone from bad to catastrophic, from my perspective,” says Susan Whitfeld-Gabrieli, a professor of psychology at Northeastern University and a research affiliate at the McGovern Institute.

“We really need to come up with novel interventions that target the neural mechanisms that we believe potentiate depression and anxiety.”

Training the brain

One approach may be to help young people learn to modulate some of the relevant brain circuitry themselves. Evidence is accumulating that practicing mindfulness — focusing awareness on the present, typically through meditation — can change patterns of brain activity associated with emotions and mental health.

“There’s been a steady flow of moderate-size studies showing that when you help people gain mindfulness through training programs, you get all kinds of benefits in terms of people feeling less stress, less anxiety, fewer negative emotions, and sometimes more positive ones as well,” says Gabrieli, who is also a professor of brain and cognitive sciences at MIT. “Those are the things you wish for people.”

“If there were a medicine with as much evidence of its effectiveness as mindfulness, it would be flying off the shelves of every pharmacy.”

– John Gabrieli

Researchers have even begun testing mindfulness-based interventions head-to-head against standard treatments for psychiatric disorders. The results of recent studies involving hundreds of adults with anxiety disorders or depression are encouraging. “It’s just as good as the best medicines and the best behavioral treatments that we know a ton about,” Gabrieli says.

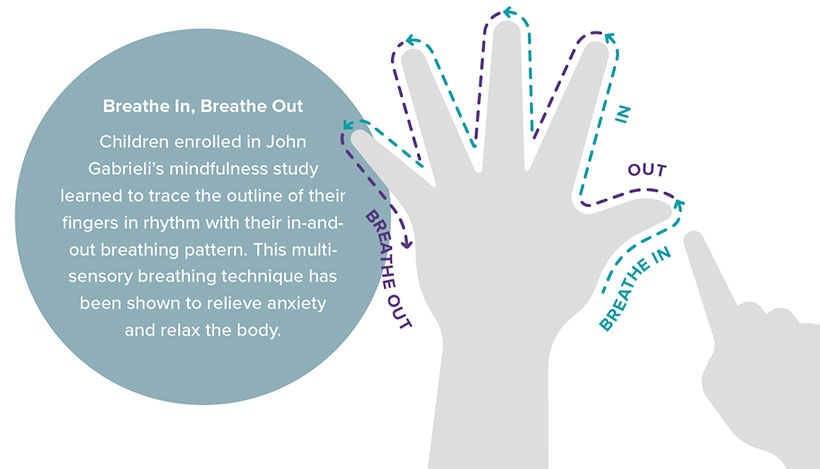

Much mindfulness research has focused on adults, but promising data about the benefits of mindfulness training for children and adolescents is emerging as well. In studies supported by the McGovern Institute’s Poitras Center for Psychiatric Disorders Research in 2019 and 2020, Gabrieli and Whitfield-Gabrieli found that sixth-graders in a Boston middle school who participated in eight weeks of mindfulness training experienced reductions in feelings of stress and increases in sustained attention. More recently, Gabrieli and Whitfeld-Gabrieli’s teams have shown how new tools can support mindfulness training and make it accessible to more children and their families — from a smartphone app that can be used anywhere to real-time neurofeedback inside an MRI scanner.

Mindfulness and mental health

Mindfulness is not just a practice, it is a trait — an open, non-judgmental way of attending to experiences that some people exhibit more than others. By assessing individuals’ mindfulness with questionnaires that ask about attention and awareness, researchers have found the trait associates with many measures of mental health. Gabrieli and his team measured mindfulness in children between the ages of eight and ten and found it was highest in those who were most emotionally resilient to the stress they experienced during the Covid-19 pandemic. As the team reported this year in the journal PLOS One, children who were more mindful rated the impact of the pandemic on their own lives lower than other participants in the study. They also reported lower levels of stress, anxiety, and depression.

Mindfulness doesn’t come naturally to everyone, but brains are malleable, and both children and adults can cultivate mindfulness with training and practice. In their studies of middle schoolers, Gabrieli and Whitfeld-Gabrieli showed that the emotional effects of mindfulness training corresponded to measurable changes in the brain: Functional MRI scans revealed changes in regions involved in stress, negative feelings, and focused attention.

Whitfeld-Gabrieli says if mindfulness training makes kids more resilient, it could be a valuable tool for managing symptoms of anxiety and depression before they become severe. “I think it should be part of the standard school day,” she says. “I think we would have a much happier, healthier society if we could be doing this from the ground up.”

Data from Gabrieli’s lab suggests broadly implementing mindfulness training might even pay off in terms of academic achievement. His team found in a 2019 study that middle school students who reported greater levels of mindfulness had, on average, better grades, better scores on standardized tests, fewer absences, and fewer school suspensions than their peers.

Some schools have begun making mindfulness programs available to their students. But those programs don’t reach everyone, and their type and quality vary tremendously. Indeed, not every study of mindfulness training in schools has found the program to significantly benefit participants, which may be because not every approach to mindfulness training is equally effective.

“This is where I think the science matters,” Gabrieli says. “You have to find out what kinds of supports really work and you have to execute them reasonably. A recent report from Gabrieli’s lab offers encouraging news: mindfulness training doesn’t have to be in-person. Gabrieli and his team found that children can benefit from practicing mindfulness at home with the help of an app.

When the pandemic closed schools in 2020, school-based mindfulness programs came to an abrupt halt. Soon thereafter, a group called Inner Explorer had developed a smartphone app that could teach children mindfulness at home. Gabrieli and his team were eager to find out if this easy-access tool could effectively support children’s emotional well-being.

In October of this year, they reported in the journal Mindfulness that after 40 days of app use, children between the ages of eight and ten reported less stress than they had before beginning mindfulness training. Parents reported that their children were also experiencing fewer negative emotions, such as loneliness and fear.

The outcomes suggest a path toward making evidence-based mindfulness training for children broadly accessible. “Tons of people could do this,” says Gabrieli. “It’s super scalable. It doesn’t cost money; you don’t have to go somewhere. We’re very excited about that.”

Visualizing healthy minds

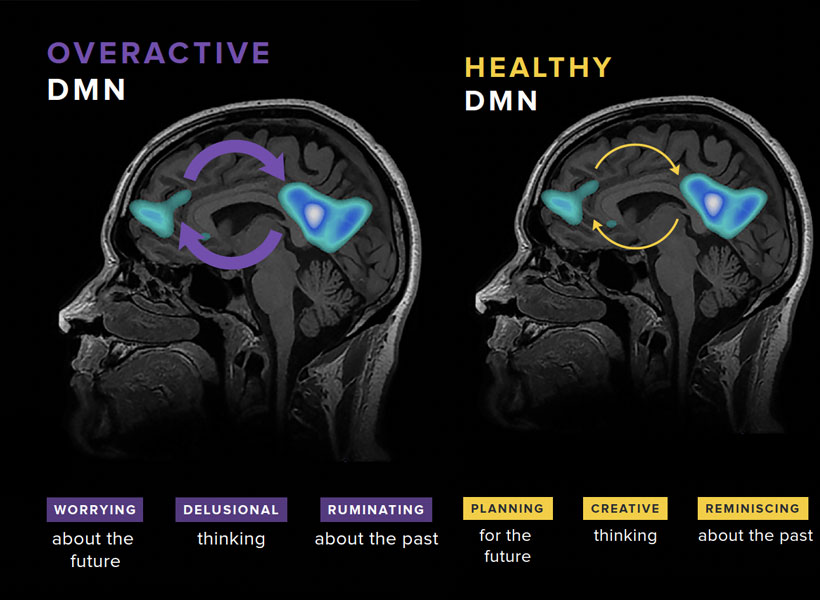

Mindfulness training may be even more effective when practitioners can visualize what’s happening in their brains. In Whitfeld-Gabrieli’s lab, teenagers have had a chance to slide inside an MRI scanner and watch their brain activity shift in real time as they practiced mindfulness meditation. The visualization they see focuses on the brain’s default mode network (DMN), which is most active when attention is not focused on a particular task. Certain patterns of activity in the DMN have been linked to depression, anxiety, and other psychiatric conditions, and mindfulness training may help break these patterns.

Whitfeld-Gabrieli explains that when the mind is free to wander, two hubs of the DMN become active. “Typically, that means we’re engaged in some kind of mental time travel,” she says. That might mean reminiscing about the past or planning for the future, but can be more distressing when it turns into obsessive rumination or worry. In people with anxiety, depression, and psychosis, these network hubs are often hyperconnected.

“It’s almost as if they’re hijacked,” Whitfeld-Gabrieli says. “The more they’re correlated, the more psychopathology one might be experiencing. We wanted to unlock that hyperconnectivity for kids who are suffering from depression and anxiety.” She hoped that by replacing thoughts of the past and the future with focus on the present, mindfulness meditation would rein in overactive DMNs, and she wanted a way to encourage kids to do exactly that.

The neurofeedback tool that she and her colleagues created focuses on the DMN as well as separate brain region that is called on during attention-demanding tasks. Activity in those regions is monitored with functional MRI and displayed to users in a game-like visualization. Inside the scanner, participants see how that activity changes as they focus on a meditation or when their mind wanders. As their mind becomes more focused on the present moment, changes in brain activity move a ball toward a target.

Whitfeld-Gabrieli says the real-time feedback was motivating for adolescents who participated in a recent study, who all had histories of anxiety or depression. “They’re training their brain to tune their mind, and they love it,” she says.

In March, she and her team reported in Molecular Psychiatry that the neurofeedback tool helped those study participants reduce connectivity in the DMN and engage a more desirable brain state. It’s not the first success the team has had with the approach. Previously, they found that the decreases in DMN connectivity brought about by mindfulness meditation with neurofeedback were associated with reduced hallucinations for patients with schizophrenia. Testing the clinical benefits of the approach in teens is on the horizon; Whitfeld-Gabrieli and her collaborators plan to investigate how mindfulness meditation with real-time neurofeedback affects depression symptoms in an upcoming clinical trial.

Whitfeld-Gabrieli emphasizes that the neurofeedback is a training tool, helping users improve mindfulness techniques they can later call on anytime, anywhere. While that training currently requires time inside an MRI scanner, she says it may be possible create an EEG-based version of the approach, which could be deployed in doctors’ offices and other more accessible settings.

Both Gabrieli and Whitfeld-Gabrieli continue to explore how mindfulness training impacts different aspects of mental health, in both children and adults and with a range of psychiatric conditions. Whitfeld-Gabrieli expects it will be one powerful tool for combating a youth mental health crisis for which there will be no single solution. “I think it’s going to take a village,” she says. “We are all going to have to work together, and we’ll have to come up some really innovative ways to help.”