Adolescents’ willingness to explore is shaped by socioeconomic status

Reluctance to explore may limit learning for students from less affluent backgrounds.

Exploration is essential to learning—and a new study from scientists at MIT’s McGovern Institute suggests that students may be less willing to explore if they come from a low socioeconomic environment. The study, which focused on adolescents and was published July 9, 2025, in the journal Nature Communications, shows how differences in learning strategies might contribute to socioeconomic-related disparities in academic achievement.

Students with low socioeconomic status (SES)—a measure that takes into account parents’ income levels and educational attainment—tend to lag behind their higher-SES peers academically. Limited resources at home can restrict access to educational tools and experiences, likely contributing to these disparities. But the new study, led by McGovern Institute Investigator John Gabrieli, shows that students from low-SES backgrounds may approach learning differently, too.

“We often think about external factors when we think about socioeconomic differences in learning, but kids’ mindsets and internal factors can also play a role,” says Alexandra Decker, a postdoctoral fellow in Gabrieli’s lab who ran the study. Understanding such differences can help educators develop strategies to reduce disparities and help all students succeed.

The value of exploration

Exploration is a vital part of development, particularly during adolescence. By trying new things and testing limits, children begin to find their way in the world, discovering the subjects and experiences that motivate them. That’s important for obtaining new knowledge, both in and out of school. “There’s a lot of research suggesting that exploration is a really important mechanism that children use for learning,” Decker says. “Exploring their environment really broadly and making mistakes helps them get the feedback that they need for learning,” she says.

Because the outcomes of exploration are unknown, this way of interacting with the world involves risk. “If you try something new, the outcome is uncertain, and it could lead to a bad outcome before things get better. You might lose out, at least in the short term. ” Decker says.

At school, students can explore in a variety of ways, such as by asking questions in class or taking on courses in unfamiliar subjects. Both are opportunities to learn something new, though they may seem less safe than sitting quietly and sticking to more comfortable coursework. Decker points out that this kind of exploration might feel particularly risky when students feel they lack the resources to compensate if things don’t go well.

“If you’re in an environment that’s really enriching, you have resources to compensate for challenges that might be accrued through exploring. If you take a new course and you struggle, you can use your resources to get a tutor and overcome these challenges. Your environment can support exploration and its costs,” she says. “But if you’re in an environment where you don’t have resources to compensate for bad outcomes, you might not take that course that could lead to unknown outcomes.”

Risk-benefit analysis

To investigate the relationship between SES and exploration, Gabrieli’s team had students play a computer game in which they earned points for pumping up balloons as much as possible without popping them. The most successful strategy was to explore the limits early on by pumping the first balloons until they popped, thereby learning when to stop with future balloons. A less exploratory approach could keep all the balloons intact, but earn fewer points over the course of the game.

The students who participated in the study were between the ages of 12 and 14 and came from families with a wide range of SES. Those from lower-SES backgrounds were less likely to explore in the balloon pumping task, resulting in lower outcomes in the game. What’s more, the researchers found a relationship between students’ exploration in the game and their real-world academic performance. Those who explored the least in the balloon-popping game had lower grades than students who explored more. For students at lower-SES levels, reduced exploration also correlated to lower scores on standardized tests of academic skills.

The researchers took a closer look at the data to investigate why some students explored more than others in their game. Their analysis indicated that students who were reluctant to explore were more strongly motivated by avoiding losses than students who had pushed the limits as they pumped their balloons.

The finding suggests that potential losses might be particularly distressing to lower-SES students, says Gabrieli, who is also the Grover Hermann Professor of Health Sciences and Technology and a professor of brain and cognitive sciences at MIT. Decker adds students from less affluent backgrounds may have found losses to be more consequential than they are for students whose families have more resources, so it makes sense that those students might take greater pains to avoid them.

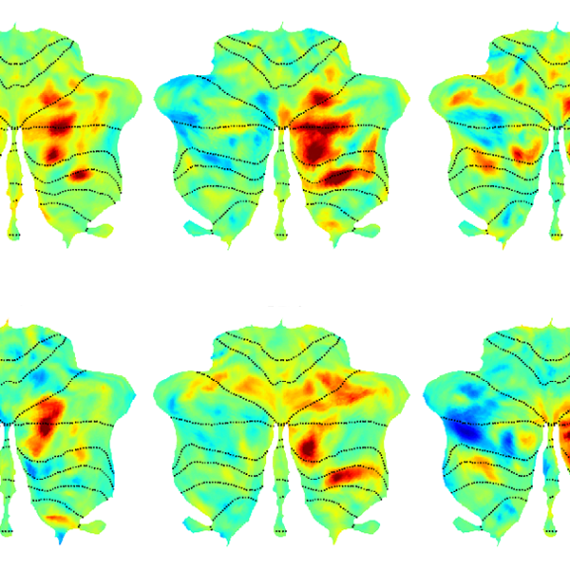

This is not the first time Gabrieli’s group has found that evidence of differences in the ways students from different socioeconomic backgrounds make decisions. In a brain imaging study published last year, they found that the brains of adolescents from low-SES backgrounds respond less to rewards than the brains of their higher-SES peers. “How you think about the world—in terms of what’s rewarding, risks worth taking or not taking—seems strongly influenced by the environment that you’re growing up in,” he says.

Decker notes that regardless of SES, students in the study were generally more willing to explore when they had experienced more recent successes in the task. This finding, along with what the team learned about how loss aversion curtails exploration, suggest strategies that educators might use to encourage more exploration in the classroom. “Low-stakes opportunities for kids to engage in exploratory risk-taking with positive feedback could go a long way to helping kids feel more comfortable exploring,” Decker says.