Who discovered neurons?

A discovery by Spanish artist and neuroscientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal would forever transform our knowledge of the brain and how it works.

On this day, December 10th, nearly 120 years ago, Santiago Ramón y Cajal received a Nobel Prize for capturing and interpreting the very first images of the brain’s most essential components — neurons.

“Many scientists consider Cajal the progenitor of neuroscience because he was the first to really see the brain for what it was: a computational engine made up of individual units,” says Mark Harnett, an investigator at the McGovern Institute and an associate professor in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences. His lab explores how the biophysical features of neurons enable them to perform complex computations that drive thought and behavior.

For Harnett, Cajal is one of the greatest scientific minds to have helped us understand ourselves and our place in the world. Cajal was the first to uncover what neurons look like and propose how they function — equipping the field to solve a slew of the mind’s mysteries. Scientists built on this framework to learn how these remarkable cells relay information — by zapping electrical signals to each other — so we can think, feel, move, communicate, and create.

From art to science and back again

Cajal was born on May 1, 1852, in a small village nestled in the Spanish countryside. It was there Cajal fell deeply and madly in love with … art. But his father was a physician, and urged him to trade his sketches for a scalpel. Begrudgingly, Cajal eventually did. After graduating from medical school in 1873, he worked as an army doctor, but around 1880, he turned his attention to studying the nervous system.

Nineteenth-century scientists didn’t think of the brain as a network of cells but more as plumbing, like the blood vessels in the circulatory system — a series of hollow tubes through which information somehow flowed. Cajal and others were skeptical of this perspective, yet had no way of visualizing the brain at a detailed, cellular level to confirm their suspicions. Scientists at the time stained thin slices of tissue to make cells visible under a microscope, but even the most sophisticated methods stained all cells at once, leaving an indecipherable mass under the microscope’s lens.

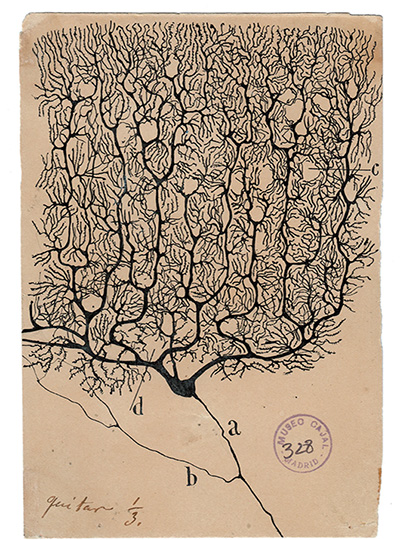

This changed in 1887 when Cajal encountered a technique devised by Camillo Golgi that stained only some cells. “Rather than seeing all the cells simultaneously, you saw one at a time,” Harnett explains, making it easier to view a cell’s precise form (Golgi shared the 1906 Nobel Prize with Cajal for this method). If he could refine Golgi’s approach and apply it to neural tissue, Cajal thought, he might finally determine the brain’s architecture.

When he did, a remarkable landscape appeared — black bulbs with sprawling branches, each casting a stringy silhouette. The scene awakened a prior passion. While viewing brain slices under a microscope, Cajal drew what he saw, with surgical precision and an artist’s eye. He had captured — for the first time — the mind’s timberland of cells.

A new theory of the mind

Cajal’s illustrations revealed that brain cells did not form a singular plumbing network, but were distinctly separate, with small gaps between them. “This completely upended what people at the time thought about the brain,” Harnett explains. “It wasn’t made up of connected tubes, but individual cells,” which a few years later in 1891 would be called neurons. Over nearly five decades Cajal created around 2,900 drawings — a collage of neurons from humans and a menagerie of fauna: mice, pigeons, lizards, newts, and fish — spanning a host of cell types, from Purkinje cells to basket and chandelier interneurons.

“Part of Cajal’s genius was that he proposed what the incredible anatomical diversity among neurons meant. He reasoned that maybe one part of the cell could work like an antenna to take in signals, and another might be a cable to send signals out. Cajal was already thinking about input and output at neurons, and synapses as points of contact between them,” Harnett notes. “Each neuron becomes a very complex engine for computation, as opposed to tube-based things that can’t really compute.”

Cajal’s notion that the brain was a network of individual cells would come to be known as the neuron doctrine, a bedrock principle that underlies all of neuroscience today. In his autobiography, Cajal describes neurons as “the mysterious butterflies of the soul, the beating of whose wings may someday – who knows? – clarify the secret of mental life.” And in many ways, they have.

One scientist’s enduring influence

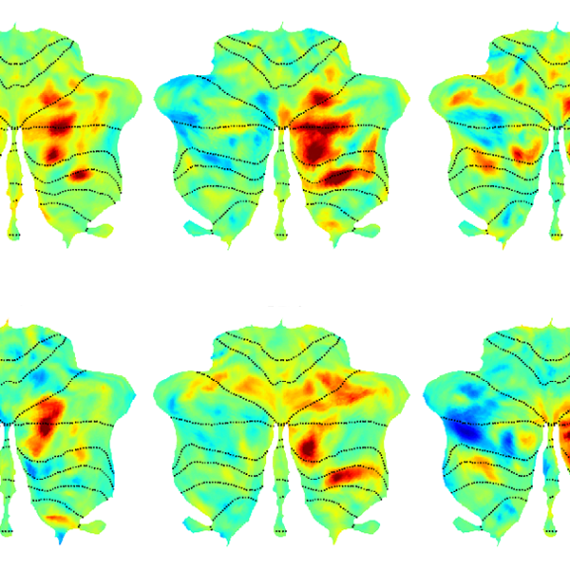

Much of scientists’ current approach to studying the brain is guided by Cajal’s blueprint. This is certainly true for the Harnett lab. “As many in the field do, we share Cajal’s aspiration to apply cutting-edge imaging to reveal hidden aspects of the brain and hypothesize about their function,” Harnett says. “Thankfully, unlike Cajal, we now have the advantage of functional tests to try to validate our hypotheses.”

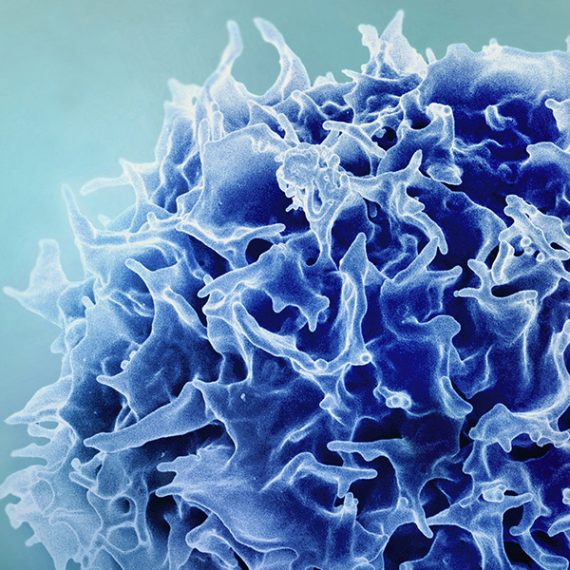

In a study published in 2022, the Harnett lab used a super-resolution imaging tool to find that filopodia — tiny structures that protrude from dendrites (the signal-receiving “antennas” of neurons) — were far more abundant in the brain than previously thought. Through a battery of tests, they found that these “silent synapses” can become active to facilitate new neural connections. Such pliable sites were believed to only be present very early in life, but the researchers observed filopodia in adult mice, suggesting that they support continuous learning and computational flexibility over the lifespan.

Harnett explains that Cajal’s impact extends beyond neuroscience. “Where does the power of artificial intelligence (AI) come from? It comes, originally, from Cajal.” It’s no wonder, he says, that AI uses neural networks — a mimicry of one of nature’s most powerful designs, first described by Cajal. “The idea that neurons are computational units is really critical to the power and complexity you can achieve within a network. Cajal even hypothesized that changing the strength of signaling between neurons was how learning worked, an idea that was later validated and became one of the critical insights for revolutionizing deep learning in AI.”

By unveiling what’s really happening beneath our skulls, Cajal’s work would both motivate and guide studies of the brain for over a hundred years to come. “Many of his early hypotheses have proven to be true decades and decades later,” Harnett says. “He has and continues to inspire generations of neuroscientists.”