The platform, called Reprogrammable ADAR Sensors, or RADARS, even allowed the team to target and kill a specific cell type. The team said RADARS could one day help researchers detect and selectively kill tumor cells, or edit the genome in specific cells. The study appears today in Nature Biotechnology and was led by co-first authors Kaiyi Jiang (MIT), Jeremy Koob (Broad), Xi Chen (Broad), Rohan Krajeski (MIT), and Yifan Zhang (Broad).

“One of the revolutions in genomics has been the ability to sequence the transcriptomes of cells,” said Fei Chen, a core institute member at the Broad, Merkin Fellow, assistant professor at Harvard University, and co-corresponding author on the study. “That has really allowed us to learn about cell types and states. But, often, we haven’t been able to manipulate those cells specifically. RADARS is a big step in that direction.”

“Right now, the tools that we have to leverage cell markers are hard to develop and engineer,” added Omar Abudayyeh, a McGovern Institute Fellow and co-corresponding author on the study. “We really wanted to make a programmable way of sensing and responding to a cell state.”

Jonathan Gootenberg, who is also a McGovern Institute Fellow and co-corresponding author, says that their team was eager to build a tool to take advantage of all the data provided by single-cell RNA sequencing, which has revealed a vast array of cell types and cell states in the body.

“We wanted to ask how we could manipulate cellular identities in a way that was as easy as editing the genome with CRISPR,” he said. “And we’re excited to see what the field does with it.”

Repurposing RNA editing

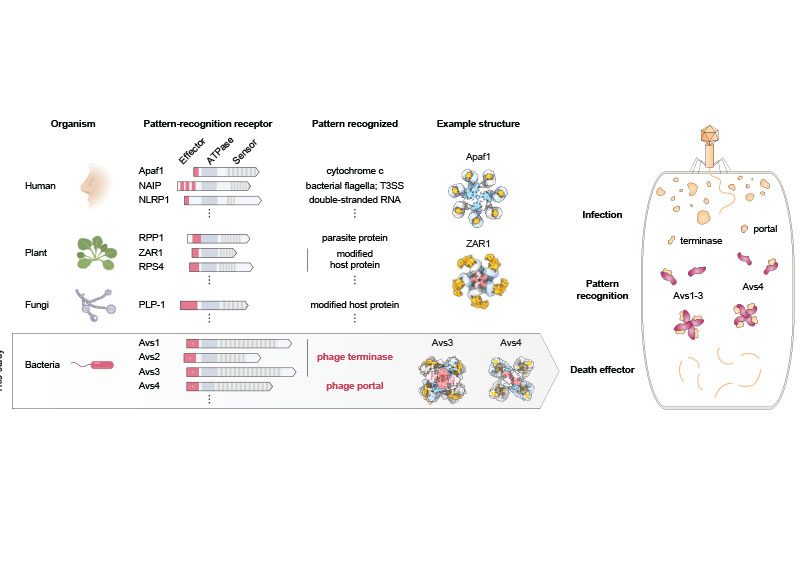

The RADARS platform generates a desired protein when it detects a specific RNA by taking advantage of RNA editing that occurs naturally in cells.

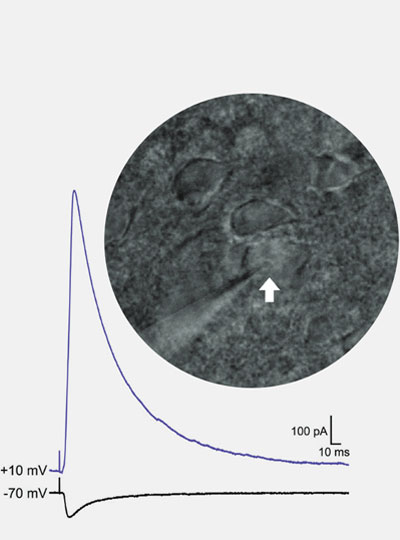

The system consists of an RNA containing two components: a guide region, which binds to the target RNA sequence that scientists want to sense in cells, and a payload region, which encodes the protein of interest, such as a fluorescent signal or a cell-killing enzyme. When the guide RNA binds to the target RNA, this generates a short double-stranded RNA sequence containing a mismatch between two bases in the sequence — adenosine (A) and cytosine (C). This mismatch attracts a naturally occurring family of RNA-editing proteins called adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs).

In RADARS, the A-C mismatch appears within a “stop signal” in the guide RNA, which prevents the production of the desired payload protein. The ADARs edit and inactivate the stop signal, allowing for the translation of that protein. The order of these molecular events is key to RADARS’s function as a sensor; the protein of interest is produced only after the guide RNA binds to the target RNA and the ADARs disable the stop signal.

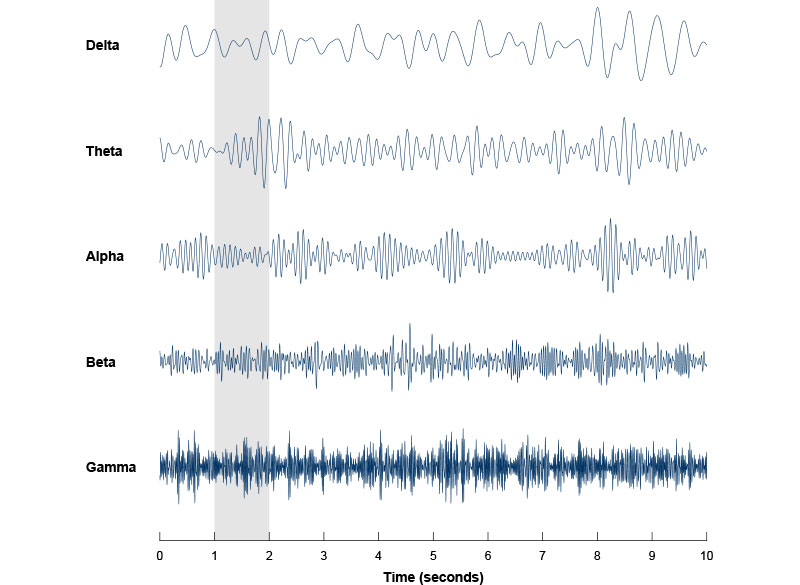

The team tested RADARS in different cell types and with different target sequences and protein products. They found that RADARS distinguished between kidney, uterine, and liver cells, and could produce different fluorescent signals as well as a caspase, an enzyme that kills cells. RADARS also measured gene expression over a large dynamic range, demonstrating their utility as sensors.

Most systems successfully detected target sequences using the cell’s native ADAR proteins, but the team found that supplementing the cells with additional ADAR proteins increased the strength of the signal. Abudayyeh says both of these cases are potentially useful; taking advantage of the cell’s native editing proteins would minimize the chance of off-target editing in therapeutic applications, but supplementing them could help produce stronger effects when RADARS are used as a research tool in the lab.

On the radar

Abudayyeh, Chen, and Gootenberg say that because both the guide RNA and payload RNA are modifiable, others can easily redesign RADARS to target different cell types and produce different signals or payloads. They also engineered more complex RADARS, in which cells produced a protein if they sensed two RNA sequences and another if they sensed either one RNA or another. The team adds that similar RADARS could help scientists detect more than one cell type at the same time, as well as complex cell states that can’t be defined by a single RNA transcript.

Ultimately, the researchers hope to develop a set of design rules so that others can more easily develop RADARS for their own experiments. They suggest other scientists could use RADARS to manipulate immune cell states, track neuronal activity in response to stimuli, or deliver therapeutic mRNA to specific tissues.

“We think this is a really interesting paradigm for controlling gene expression,” said Chen. “We can’t even anticipate what the best applications will be. That really comes from the combination of people with interesting biology and the tools you develop.”

This work was supported by the The McGovern Institute Neurotechnology (MINT) program, the K. Lisa Yang and Hock E. Tan Center for Molecular Therapeutics in Neuroscience, the G. Harold & Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Impetus Grants, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Google Ventures, FastGrants, the McGovern Institute, National Institutes of Health, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the Searle Scholars Foundation, the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, and the Merkin Institute.