By mutating a single gene, researchers at MIT and Duke have produced mice with two of the most common traits of autism — compulsive, repetitive behavior and avoidance of social interaction.

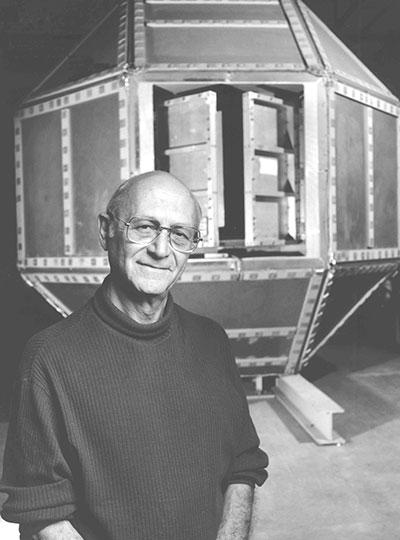

They further showed that this gene, which is also implicated in many cases of human autism, appears to produce autistic behavior by interfering with communication between brain cells. The finding, reported in the March 20 online edition of Nature, could help researchers find new pathways for developing drugs to treat autism, says senior author Guoping Feng, professor of brain and cognitive sciences and member of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT.

About one in 110 children in the United States has an autism spectrum disorder, which can range in severity and symptoms but usually includes difficulties with language in addition to social avoidance and repetitive behavior. There are currently no effective drugs to treat autism, but the new finding could help uncover new drug targets, Feng says.

“We now have a very robust model with a known cause for autistic-like behaviors. We can figure out the neural circuits responsible for these behaviors, which could lead to novel targets for treatment,” he says.

The new mouse model also gives researchers a new way to test potential autism drugs before trying them in human patients.

A genetic disorder

In the past 10 years, large-scale genetic studies have identified hundreds of gene mutations that occur more frequently in autistic patients than in the general population. However, each patient has only one or a handful of those mutations, making it difficult to develop drugs against the disease.

In this study, the researchers focused on one of the most common of those genes, known as Shank3. The protein encoded by Shank3 is found in synapses — the junctions between brain cells that allow them to communicate with each other. Feng, who joined MIT and the McGovern Institute last year, began studying Shank3 a few years ago because he thought that synaptic proteins might contribute to autism and similar brain disorders, such as obsessive compulsive disorder.

At a synapse, one cell sends messages by releasing chemicals called neurotransmitters, which interact with the cell receiving the signal (known as the postsynaptic cell). This signal provokes the postsynaptic cell to alter its activity in some way — for example, turning a gene on or off. Shank3 is a “scaffold” protein, meaning that it helps to organize the hundreds of other proteins clustered on the postsynaptic cell membrane, which are necessary to coordinate the cell’s response to synaptic signals.

Feng targeted Shank3 because it is found primarily in a part of the brain called the striatum, which is involved in motor activity, decision-making and the emotional aspects of behavior. Malfunctions in the striatum are associated with several brain disorders, including autism and OCD. Feng theorized that those disorders might be caused by faulty synapses.

In a 2007 study, Feng showed that another postsynaptic protein found in the striatum, Sapap3, can cause OCD-like behavior in mice when mutated.

Communication problems

In the new Nature study, Feng and his colleagues found that Shank3 mutant mice showed compulsive behavior (specifically, excessive grooming) and avoidance of social interaction. “They’re just not interested in interacting with other mice,” he says.

The study, funded in part by the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative, offers the first direct evidence that mutations in Shank3 produce autistic-like behavior.

Guy Rouleau, professor of medicine at the University of Montreal, says the mouse model should give autism researchers a chance to understand the disease better and potentially develop new treatments. “It looks like this is going to be a good model that will be used to explore, more deeply, the physiology of the disorder,” says Rouleau, who was not involved in this research.

Even though only a small percentage of autistic patients have mutations in Shank3, Feng believes that many other cases may be caused by disruptions of other synaptic proteins. He is now doing a study, with researchers from the Broad Institute, to determine whether mutations in a group of other synaptic genes are associated with autism in human patients.

If that turns out to be the case, it should be possible to develop treatments that restore synaptic function, regardless of which particular synaptic protein is defective in the individual patient, Feng says.

Feng performed some of the research while at Duke, and several of his former Duke colleagues are authors on the Nature paper, including lead author Joao Peca and Professor Christopher Lascola.