In a fitting sequel to its entrepreneurship “boot camp” educational lecture series last fall, the MIT Future Founders Initiative has announced the MIT Future Founders Prize Competition, supported by Northpond Ventures, and named the MIT faculty cohort that will participate in this year’s competition. The Future Founders Initiative was established in 2020 to promote female entrepreneurship in biotech.

Despite increasing representation at MIT, female science and engineering faculty found biotech startups at a disproportionately low rate compared with their male colleagues, according to research led by the initiative’s founders, MIT Professor Sangeeta Bhatia, MIT Professor and President Emerita Susan Hockfield, and MIT Amgen Professor of Biology Emerita Nancy Hopkins. In addition to highlighting systemic gender imbalances in the biotech pipeline, the initiative’s founders emphasize that the dearth of female biotech entrepreneurs represents lost opportunities for society as a whole — a bottleneck in the proliferation of publicly accessible medical and technological innovation.

“A very common myth is that representation of women in the pipeline is getting better with time … We can now look at the data … and simply say, ‘that’s not true’,” said Bhatia, who is the John and Dorothy Wilson Professor of Health Sciences and Technology and Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, and a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science, in an interview for the March/April 2021 MIT Faculty Newsletter. “We need new solutions. This isn’t just about waiting and being optimistic.”

Inspired by generous funding from Northpond Labs, the research and development-focused affiliate of Northpond Ventures, and by the success of other MIT prize incentive competitions such as the Climate Tech and Energy Prize, the Future Founders Initiative Prize Competition will be structured as a learning cohort in which participants will be supported in commercializing their existing inventions with instruction in market assessments, fundraising, and business capitalization, as well as other programming. The program, which is being run as a partnership between the MIT School of Engineering and the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship, provides hands-on opportunities to learn from industry leaders about their experiences, ranging from licensing technology to creating early startup companies. Bhatia and Kit Hickey, an entrepreneur-in-residence at the Martin Trust Center and senior lecturer at the MIT Sloan School of Management, are co-directors of the program.

“The competition is an extraordinary effort to increase the number of female faculty who translate their research and ideas into real-world applications through entrepreneurship,” says Anantha Chandrakasan, dean of the MIT School of Engineering and Vannevar Bush Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. “Our hope is that this likewise serves as an opportunity for participants to gain exposure and experience to the many ways in which they could achieve commercial impact through their research.”

At the end of the program, the cohort members will pitch their ideas to a selection committee composed of MIT faculty, biotech founders, and venture capitalists. The grand prize winner will receive $250,000 in discretionary funds, and two runners-up will receive $100,000. The winners will be announced at a showcase event, at which the entire cohort will present their work. All participants will also receive a $10,000 stipend for participating in the competition.

“The biggest payoff is not identifying the winner of the competition,” says Bhatia. “Really, what we are doing is creating a cohort … and then, at the end, we want to create a lot of visibility for these women and make them ‘top of mind’ in the community.”

The Selection Committee members for the MIT Future Founders Prize Competition are:

- Bill Aulet, professor of the practice in the MIT Sloan School of Management and managing director of the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship

- Sangeeta Bhatia, the John and Dorothy Wilson Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT; a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science; and founder of Hepregen, Glympse Bio, and Satellite Bio

- Kit Hickey, senior lecturer in the MIT Sloan School of Management and entrepreneur-in-residence at the Martin Trust Center

- Susan Hockfield, MIT president emerita and professor of neuroscience

- Andrea Jackson, director at Northpond Ventures

- Harvey Lodish, professor of biology and biomedical engineering at MIT and founder of Genzyme, Millennium, and Rubius

- Fiona Murray, associate dean for innovation and inclusion in the MIT Sloan School of Management; the William Porter Professor of Entrepreneurship; co-director of the MIT Innovation Initiative; and faculty director of the MIT Legatum Center

- Amy Schulman, founding CEO of Lyndra Therapeutics and partner at Polaris Partners

- Nandita Shangari, managing director at Novartis Venture Fund

“As an investment firm dedicated to supporting entrepreneurs, we are acutely aware of the limited number of companies founded and led by women in academia. We believe humanity should be benefiting from brilliant ideas and scientific breakthroughs from women in science, which could address many of the world’s most pressing problems. Together with MIT, we are providing an opportunity for women faculty members to enhance their visibility and gain access to the venture capital ecosystem,” says Andrea Jackson, director at Northpond Ventures.

“This first cohort is representative of the unrealized opportunity this program is designed to capture. While it will take a while to build a robust community of connections and role models, I am pleased and confident this program will make entrepreneurship more accessible and inclusive to our community, which will greatly benefit society,” says Susan Hockfield, MIT president emerita.

The MIT Future Founders Prize Competition cohort members were selected from schools across MIT, including the School of Science, the School of Engineering, and Media Lab within the School of Architecture and Planning. They are:

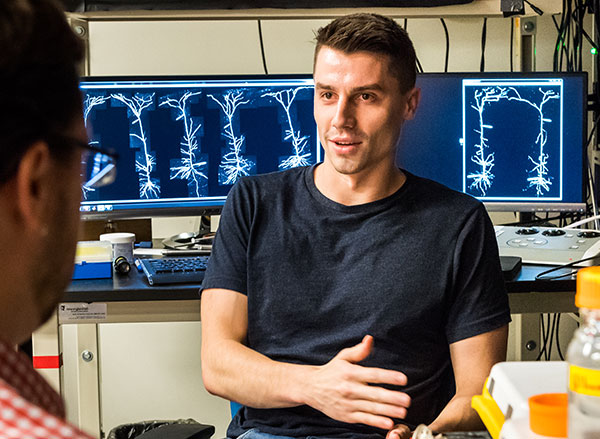

Polina Anikeeva is professor of materials science and engineering and brain and cognitive sciences, an associate member of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research, and the associate director of the Research Laboratory of Electronics. She is particularly interested in advancing the possibility of future neuroprosthetics, through biologically-informed materials synthesis, modeling, and device fabrication. Anikeeva earned her BS in biophysics from St. Petersburg State Polytechnic University and her PhD in materials science and engineering from MIT.

Natalie Artzi is principal research scientist in the Institute of Medical Engineering and Science and an assistant professor in the department of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Through the development of smart materials and medical devices, her research seeks to “personalize” medical interventions based on the specific presentation of diseased tissue in a given patient. She earned both her BS and PhD in chemical engineering from the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology.

Laurie A. Boyer is professor of biology and biological engineering in the Department of Biology. By studying how diverse molecular programs cross-talk to regulate the developing heart, she seeks to develop new therapies that can help repair cardiac tissue. She earned her BS in biomedical science from Framingham State University and her PhD from the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Tal Cohen is associate professor in the departments of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Mechanical Engineering. She wields her understanding of how materials behave when they are pushed to their extremes to tackle engineering challenges in medicine and industry. She earned her BS, MS, and PhD in aerospace engineering from the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology.

Canan Dagdeviren is assistant professor of media arts and sciences and the LG Career Development Professor of Media Arts and Sciences. Her research focus is on creating new sensing, energy harvesting, and actuation devices that can be stretched, wrapped, folded, twisted, and implanted onto the human body while maintaining optimal performance. She earned her BS in physics engineering from Hacettepe University, her MS in materials science and engineering from Sabanci University, and her PhD in materials science and engineering from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Ariel Furst is the Raymond (1921) & Helen St. Laurent Career Development Professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering. Her research addresses challenges in global health and sustainability, utilizing electrochemical methods and biomaterials engineering. She is particularly interested in new technologies that detect and treat disease. Furst earned her BS in chemistry at the University of Chicago and her PhD at Caltech.

Kristin Knouse is assistant professor in the Department of Biology and the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research. She develops tools to investigate the molecular regulation of organ injury and regeneration directly within a living organism with the goal of uncovering novel therapeutic avenues for diverse diseases. She earned her BS in biology from Duke University, her PhD and MD through the Harvard and MIT MD-PhD program.

Elly Nedivi is the William R. (1964) & Linda R. Young Professor of Neuroscience at the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory with joint appointments in the departments of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and Biology. Through her research of neurons, genes, and proteins, Nedivi focuses on elucidating the cellular mechanisms that control plasticity in both the developing and adult brain. She earned her BS in biology from Hebrew University and her PhD in neuroscience from Stanford University.

Ellen Roche is associate professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Institute of Medical Engineering and Science, and the W.M. Keck Career Development Professor in Biomedical Engineering. Borrowing principles and design forms she observes in nature, Roche works to develop implantable therapeutic devices that assist cardiac and other biological function. She earned her bachelor’s degree in biomedical engineering from the National University of Ireland at Galway, her MS in bioengineering from Trinity College Dublin, and her PhD from Harvard University.