Throughout the brain’s cortex, neurons are arranged in six distinctive layers, which can be readily seen with a microscope. A team of MIT and Vanderbilt University neuroscientists has now found that these layers also show distinct patterns of electrical activity, which are consistent over many brain regions and across several animal species, including humans.

The researchers found that in the topmost layers, neuron activity is dominated by rapid oscillations known as gamma waves. In the deeper layers, slower oscillations called alpha and beta waves predominate. The universality of these patterns suggests that these oscillations are likely playing an important role across the brain, the researchers say.

“When you see something that consistent and ubiquitous across cortex, it’s playing a very fundamental role in what the cortex does,” says Earl Miller, the Picower Professor of Neuroscience, a member of MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, and one of the senior authors of the new study.

Imbalances in how these oscillations interact with each other may be involved in brain disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, the researchers say.

“Overly synchronous neural activity is known to play a role in epilepsy, and now we suspect that different pathologies of synchrony may contribute to many brain disorders, including disorders of perception, attention, memory, and motor control. In an orchestra, one instrument played out of synchrony with the rest can disrupt the coherence of the entire piece of music,” says Robert Desimone, director of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research and one of the senior authors of the study.

André Bastos, an assistant professor of psychology at Vanderbilt University, is also a senior author of the open-access paper, which appears today in Nature Neuroscience. The lead authors of the paper are MIT research scientist Diego Mendoza-Halliday and MIT postdoc Alex Major.

Layers of activity

The human brain contains billions of neurons, each of which has its own electrical firing patterns. Together, groups of neurons with similar patterns generate oscillations of electrical activity, or brain waves, which can have different frequencies. Miller’s lab has previously shown that high-frequency gamma rhythms are associated with encoding and retrieving sensory information, while low-frequency beta rhythms act as a control mechanism that determines which information is read out from working memory.

His lab has also found that in certain parts of the prefrontal cortex, different brain layers show distinctive patterns of oscillation: faster oscillation at the surface and slower oscillation in the deep layers. One study, led by Bastos when he was a postdoc in Miller’s lab, showed that as animals performed working memory tasks, lower-frequency rhythms generated in deeper layers regulated the higher-frequency gamma rhythms generated in the superficial layers.

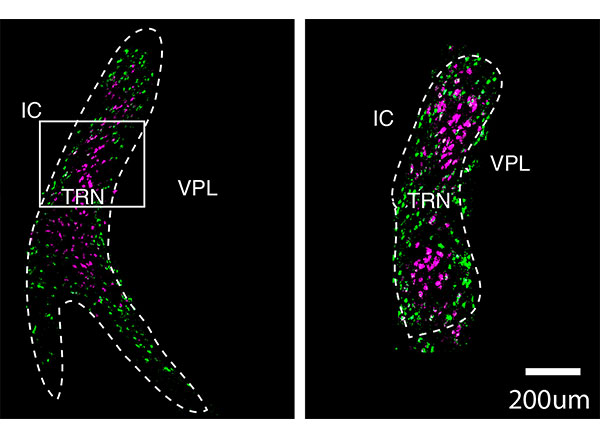

In addition to working memory, the brain’s cortex also is the seat of thought, planning, and high-level processing of emotion and sensory information. Throughout the regions involved in these functions, neurons are arranged in six layers, and each layer has its own distinctive combination of cell types and connections with other brain areas.

“The cortex is organized anatomically into six layers, no matter whether you look at mice or humans or any mammalian species, and this pattern is present in all cortical areas within each species,” Mendoza-Halliday says. “Unfortunately, a lot of studies of brain activity have been ignoring those layers because when you record the activity of neurons, it’s been difficult to understand where they are in the context of those layers.”

In the new paper, the researchers wanted to explore whether the layered oscillation pattern they had seen in the prefrontal cortex is more widespread, occurring across different parts of the cortex and across species.

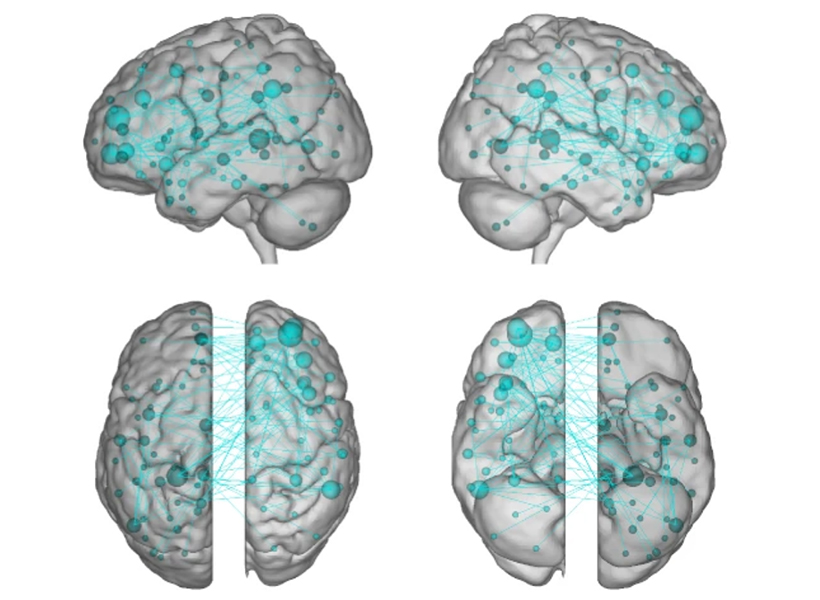

Using a combination of data acquired in Miller’s lab, Desimone’s lab, and labs from collaborators at Vanderbilt, the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, and the University of Western Ontario, the researchers were able to analyze 14 different areas of the cortex, from four mammalian species. This data included recordings of electrical activity from three human patients who had electrodes inserted in the brain as part of a surgical procedure they were undergoing.

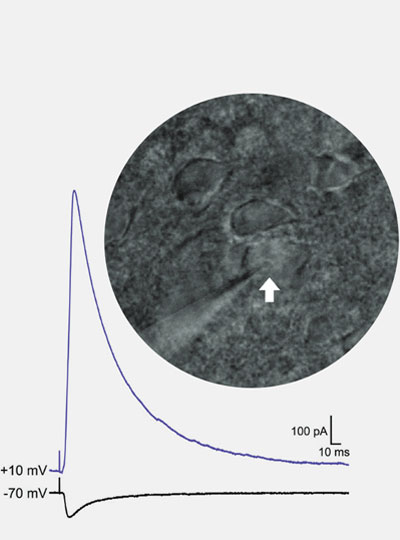

Recording from individual cortical layers has been difficult in the past, because each layer is less than a millimeter thick, so it’s hard to know which layer an electrode is recording from. For this study, electrical activity was recorded using special electrodes that record from all of the layers at once, then feed the data into a new computational algorithm the authors designed, termed FLIP (frequency-based layer identification procedure). This algorithm can determine which layer each signal came from.

“More recent technology allows recording of all layers of cortex simultaneously. This paints a broader perspective of microcircuitry and allowed us to observe this layered pattern,” Major says. “This work is exciting because it is both informative of a fundamental microcircuit pattern and provides a robust new technique for studying the brain. It doesn’t matter if the brain is performing a task or at rest and can be observed in as little as five to 10 seconds.”

Across all species, in each region studied, the researchers found the same layered activity pattern.

“We did a mass analysis of all the data to see if we could find the same pattern in all areas of the cortex, and voilà, it was everywhere. That was a real indication that what had previously been seen in a couple of areas was representing a fundamental mechanism across the cortex,” Mendoza-Halliday says.

Maintaining balance

The findings support a model that Miller’s lab has previously put forth, which proposes that the brain’s spatial organization helps it to incorporate new information, which carried by high-frequency oscillations, into existing memories and brain processes, which are maintained by low-frequency oscillations. As information passes from layer to layer, input can be incorporated as needed to help the brain perform particular tasks such as baking a new cookie recipe or remembering a phone number.

“The consequence of a laminar separation of these frequencies, as we observed, may be to allow superficial layers to represent external sensory information with faster frequencies, and for deep layers to represent internal cognitive states with slower frequencies,” Bastos says. “The high-level implication is that the cortex has multiple mechanisms involving both anatomy and oscillations to separate ‘external’ from ‘internal’ information.”

Under this theory, imbalances between high- and low-frequency oscillations can lead to either attention deficits such as ADHD, when the higher frequencies dominate and too much sensory information gets in, or delusional disorders such as schizophrenia, when the low frequency oscillations are too strong and not enough sensory information gets in.

“The proper balance between the top-down control signals and the bottom-up sensory signals is important for everything the cortex does,” Miller says. “When the balance goes awry, you get a wide variety of neuropsychiatric disorders.”

The researchers are now exploring whether measuring these oscillations could help to diagnose these types of disorders. They are also investigating whether rebalancing the oscillations could alter behavior — an approach that could one day be used to treat attention deficits or other neurological disorders, the researchers say.

The researchers also hope to work with other labs to characterize the layered oscillation patterns in more detail across different brain regions.

“Our hope is that with enough of that standardized reporting, we will start to see common patterns of activity across different areas or functions that might reveal a common mechanism for computation that can be used for motor outputs, for vision, for memory and attention, et cetera,” Mendoza-Halliday says.

The research was funded by the U.S. Office of Naval Research, the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the U.S. National Eye Institute, the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health, the Picower Institute, a Simons Center for the Social Brain Postdoctoral Fellowship, and a Canadian Institutes of Health Postdoctoral Fellowship.