The secret to the success of MIT’s Simons Center for the Social Brain is in the name. With a founding philosophy of “collaboration and community” that has supported scores of scientists across more than a dozen Boston-area research institutions, the SCSB advances research by being inherently social.

SCSB’s mission is “to understand the neural mechanisms underlying social cognition and behavior and to translate this knowledge into better diagnosis and treatment of autism spectrum disorders.” When Director Mriganka Sur founded the center in 2012 in partnership with the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) of Jim and Marilyn Simons, he envisioned a different way to achieve urgently needed research progress than the traditional approach of funding isolated projects in individual labs. Sur wanted SCSB’s contribution to go beyond papers, though it has generated about 350 and counting. He sought the creation of a sustained, engaged autism research community at MIT and beyond.

“When you have a really big problem that spans so many issues — a clinical presentation, a gene, and everything in between — you have to grapple with multiple scales of inquiry,” says Sur, the Newton Professor of Neuroscience in MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences (BCS) and The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory. “This cannot be solved by one person or one lab. We need to span multiple labs and multiple ways of thinking. That was our vision.”

In parallel with a rich calendar of public colloquia, lunches, and special events, SCSB catalyzes multiperspective, multiscale research collaborations in two programmatic ways. Targeted projects fund multidisciplinary teams of scientists with complementary expertise to collectively tackle a pressing scientific question. Meanwhile, the center supports postdoctoral Simons Fellows with not one, but two mentors, ensuring a further cross-pollination of ideas and methods.

Complementary collaboration

In 11 years, SCSB has funded nine targeted projects. Each one, by design, involves a deep and multifaceted exploration of a major question with both fundamental importance and clinical relevance. The first project, back in 2013, for example, marshaled three labs spanning BCS, the Department of Biology, and The Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research to advance understanding of how mutation of the Shank3 gene leads to the pathophysiology of Phelan-McDermid Syndrome by working across scales ranging from individual neural connections to whole neurons to circuits and behavior.

Other past projects have applied similarly integrated, multiscale approaches to topics ranging from how 16p11.2 gene deletion alters the development of brain circuits and cognition to the critical role of the thalamic reticular nucleus in information flow during sleep and wakefulness. Two others produced deep examinations of cognitive functions: how we go from hearing a string of words to understanding a sentence’s intended meaning, and the neural and behavioral correlates of deficits in making predictions about social and sensory stimuli. Yet another project laid the groundwork for developing a new animal model for autism research.

SFARI is especially excited by SCSB’s team science approach, says Kelsey Martin, executive vice president of autism and neuroscience at the Simons Foundation. “I’m delighted by the collaborative spirit of the SCSB,” Martin says. “It’s wonderful to see and learn about the multidisciplinary team-centered collaborations sponsored by the center.”

New projects

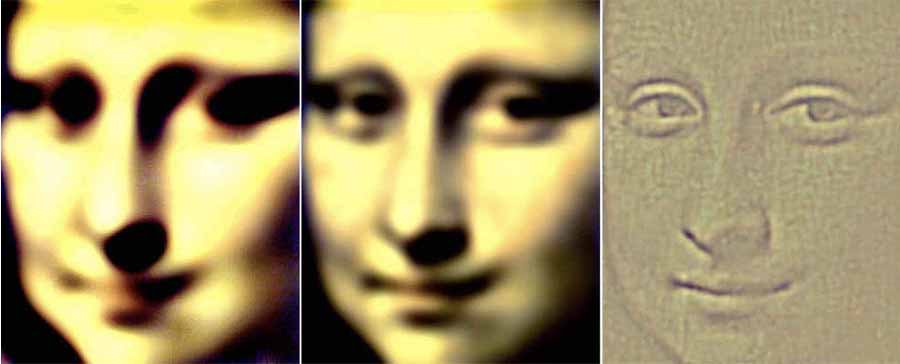

In the last year, SCSB has launched three new targeted projects. One team is investigating why many people with autism experience sensory overload and is testing potential interventions to help. The scientists hypothesize that patients experience a deficit in filtering out the mundane stimuli that neurotypical people predict are safe to ignore. Studies suggest the predictive filter relies on relatively low-frequency “alpha/beta” brain rhythms from deep layers of the cortex moderating the higher frequency “gamma” rhythms in superficial layers that process sensory information.

Together, the labs of Charles Nelson, professor of pediatrics at Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH), and BCS faculty members Bob Desimone, the Doris and Don Berkey Professor of Neuroscience at MIT and director of the McGovern Institute, and Earl K. Miller, the Picower Professor, are testing the hypothesis in two different animal models at MIT and in human volunteers at BCH. In the animals they’ll also try out a new real-time feedback system invented in Miller’s lab that can potentially correct the balance of these rhythms in the brain. And in an animal model engineered with a Shank3 mutation, Desimone’s lab will test a gene therapy, too.

“None of us could do all aspects of this project on our own,” says Miller, an investigator in the Picower Institute. “It could only come about because the three of us are working together, using different approaches.”

Right from the start, Desimone says, close collaboration with Nelson’s group at BCH has been essential. To ensure his and Miller’s measurements in the animals and Nelson’s measurements in the humans are as comparable as possible, they have tightly coordinated their research protocols.

“If we hadn’t had this joint grant we would have chosen a completely different, random set of parameters than Chuck, and the results therefore wouldn’t have been comparable. It would be hard to relate them,” says Desimone, who also directs MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research. “This is a project that could not be accomplished by one lab operating in isolation.”

Another targeted project brings together a coalition of seven labs — six based in BCS (professors Evelina Fedorenko, Edward Gibson, Nancy Kanwisher, Roger Levy, Rebecca Saxe, and Joshua Tenenbaum) and one at Dartmouth College (Caroline Robertson) — for a synergistic study of the cognitive, neural, and computational underpinnings of conversational exchanges. The study will integrate the linguistic and non-linguistic aspects of conversational ability in neurotypical adults and children and those with autism.

Fedorenko said the project builds on advances and collaborations from the earlier language Targeted Project she led with Kanwisher.

“Many directions that we started to pursue continue to be active directions in our labs. But most importantly, it was really fun and allowed the PIs [principal investigators] to interact much more than we normally would and to explore exciting interdisciplinary questions,” Fedorenko says. “When Mriganka approached me a few years after the project’s completion asking about a possible new targeted project, I jumped at the opportunity.”

Gibson and Robertson are studying how people align their dialogue, not only in the content and form of their utterances, but using eye contact. Fedorenko and Kanwisher will employ fMRI to discover key components of a conversation network in the cortex. Saxe will examine the development of conversational ability in toddlers using novel MRI techniques. Levy and Tenenbaum will complement these efforts to improve computational models of language processing and conversation.

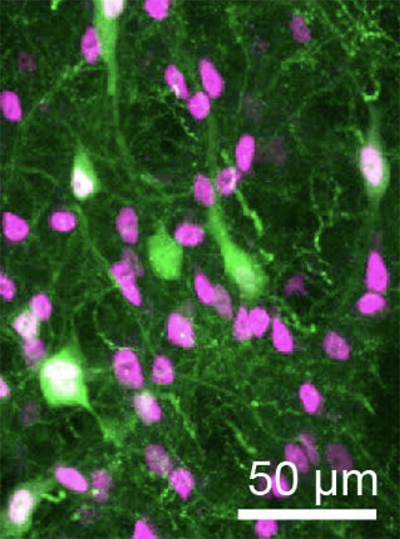

The newest Targeted Project posits that the immune system can be harnessed to help treat behavioral symptoms of autism. Four labs — three in BCS and one at Harvard Medical School (HMS) — will study mechanisms by which peripheral immune cells can deliver a potentially therapeutic cytokine to the brain. A study by two of the collaborators, MIT associate professor Gloria Choi and HMS associate professor Jun Huh, showed that when IL-17a reaches excitatory neurons in a region of the mouse cortex, it can calm hyperactivity in circuits associated with social and repetitive behavior symptoms. Huh, an immunologist, will examine how IL-17a can get from the periphery to the brain, while Choi will examine how it has its neurological effects. Sur and MIT associate professor Myriam Heiman will conduct studies of cell types that bridge neural circuits with brain circulatory systems.

“It is quite amazing that we have a core of scientists working on very different things coming together to tackle this one common goal,” Choi says. “I really value that.”

Multiple mentors

While SCSB Targeted Projects unify labs around research, the center’s Simons Fellowships unify labs around young researchers, providing not only funding, but a pair of mentors and free-flowing interactions between their labs. Fellows also gain opportunities to inform and inspire their fundamental research by visiting with patients with autism, Sur says.

“The SCSB postdoctoral program serves a critical role in ensuring that a diversity of outstanding scientists are exposed to autism research during their training, providing a pipeline of new talent and creativity for the field,” adds Martin, of the Simons Foundation.

Simons Fellows praise the extra opportunities afforded by additional mentoring. Postdoc Alex Major was a Simons Fellow in Miller’s lab and that of Nancy Kopell, a mathematics professor at Boston University renowned for her modeling of the brain wave phenomena that the Miller lab studies experimentally.

“The dual mentorship structure is a very useful aspect of the fellowship” Major says. “It is both a chance to network with another PI and provides experience in a different neuroscience sub-field.”

Miller says co-mentoring expands the horizons and capabilities of not only the mentees but also the mentors and their labs. “Collaboration is 21st century neuroscience,” Miller says. “Some our studies of the brain have gotten too big and comprehensive to be encapsulated in just one laboratory. Some of these big questions require multiple approaches and multiple techniques.”

Desimone, who recently co-mentored Seng Bum (Michael Yoo) along with BCS and McGovern colleague Mehrdad Jazayeri in a project studying how animals learn from observing others, agrees.

“We hear from postdocs all the time that they wish they had two mentors, just in general to get another point of view,” Desimone says. “This is a really good thing and it’s a way for faculty members to learn about what other faculty members and their postdocs are doing.”

Indeed, the Simons Center model suggests that research can be very successful when it’s collaborative and social.