The Office of the Vice Chancellor and the Registrar’s Office have announced this year’s Margaret MacVicar Faculty Fellows: professor of brain and cognitive sciences John Gabrieli, associate professor of literature Marah Gubar, professor of biology Adam C. Martin, and associate professor of architecture Lawrence “Larry” Sass.

For more than 30 years, the MacVicar Faculty Fellows Program has recognized exemplary and sustained contributions to undergraduate education at MIT. The program is named in honor of Margaret MacVicar, the first dean for undergraduate education and founder of the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP). New fellows are chosen every year through a competitive nomination process that includes submission of letters of support from colleagues, students, and alumni; review by an advisory committee led by the vice chancellor; and a final selection by the provost. Fellows are appointed to a 10-year term and receive $10,000 per year of discretionary funds.

Gabrieli, Gubar, Martin, and Sass join an elite group of more than 130 scholars from across the Institute who are committed to curricular innovation, excellence in teaching, and supporting students both in and out of the classroom.

John Gabrieli

“When I learned of this wonderful honor, I felt gratitude — for how MIT values teaching and learning, how my faculty colleagues bring such passion to their teaching, and how the students have such great curiosity for learning,” says new MacVicar Fellow John Gabrieli.

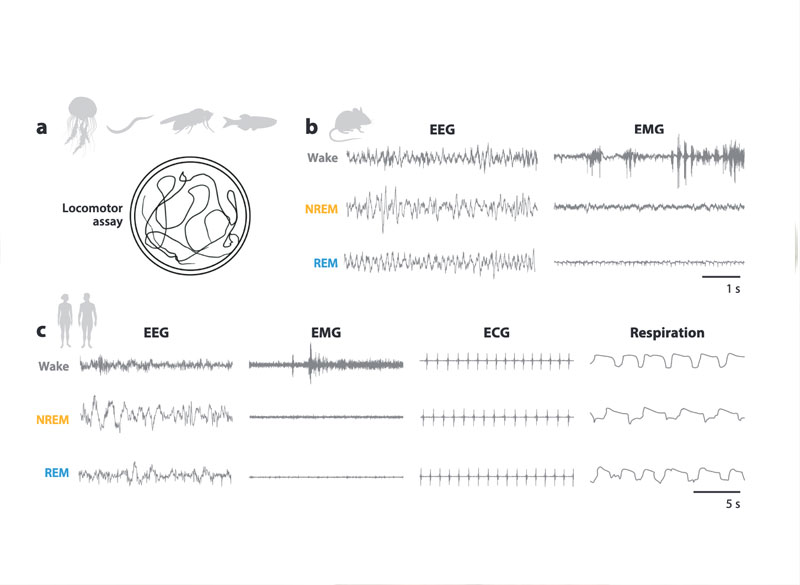

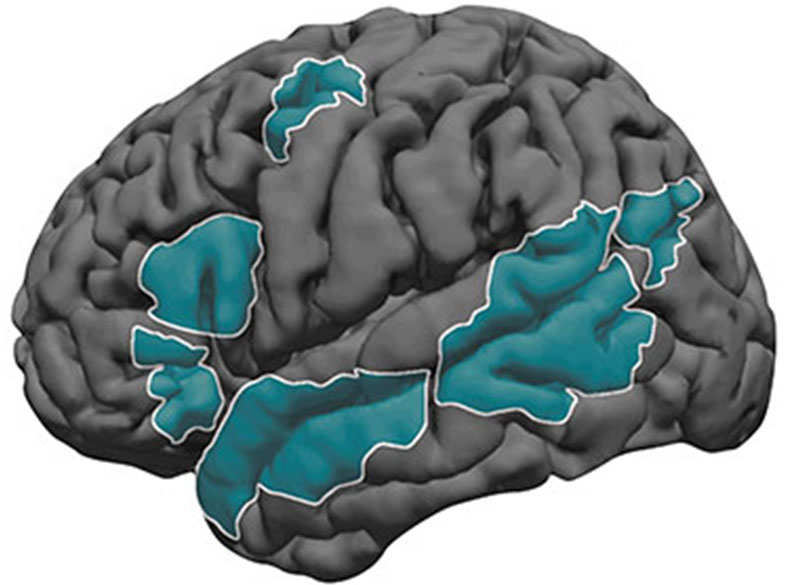

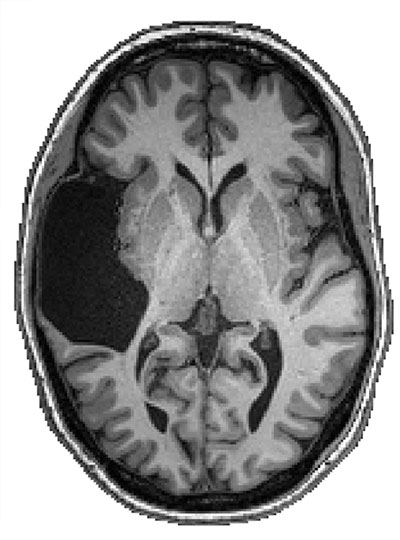

Gabrieli PhD ’87 received a bachelor’s degree in English from Yale University and his PhD in behavioral neuroscience from MIT. He is the Grover M. Hermann Professor in the Department of Brain and Cognitive sciences. Gabrieli is also an investigator in the McGovern Institute for Brain Research and the founding director of the MIT Integrated Learning Initiative (MITili). He holds appointments in the Department of Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and studies the organization of memory, thought, and emotion in the human brain.

He joined Course 9 as a professor in 2005 and since then, he has taught over 3,000 undergraduates through the department’s introductory course, 9.00 (Introduction to Psychological Science). Gabrieli was recognized with departmental awards for excellence in teaching in 2009, 2012, and 2015. Highly sought after by undergraduate researchers, the Gabrieli Laboratory (GabLab) hosts five to 10 UROPs each year.

A unique element of Gabrieli’s classes is his passionate, hands-on teaching style and his use of interactive demonstrations, such as optical illusions and personality tests, to help students grasp some of the most fundamental topics in psychology.

His former teaching assistant Daniel Montgomery ’22 writes, “I was impressed by his enthusiasm and ability to keep students engaged throughout the lectures … John clearly has a desire to help students become excited about the material he’s teaching.”

Senior Elizabeth Carbonell agrees: “The excitement professor Gabrieli brought to lectures by starting with music every time made the classroom an enjoyable atmosphere conducive to learning … he always found a way to make every lecture relatable to the students, teaching psychological concepts that would shine a light on our own human emotions.”

Lecturer and 9.00 course coordinator Laura Frawley says, “John constantly innovates … He uses research-based learning techniques in his class, including blended learning, active learning, and retrieval practice.” His findings on blended learning resulted in two MITx offerings including 9.00x (Learning and Memory), which utilizes a nontraditional approach to assignments and exams to improve how students retrieve and remember information.

In addition, he is known for being a devoted teacher who believes in caring for the student as a whole. Through MITili’s Mental Wellness Initiative, Gabrieli, along with a compassionate team of faculty and staff, are working to better understand how mental health conditions impact learning.

Associate department head and associate professor of brain and cognitive sciences Josh McDermott calls him “an exceptional educator who has left his mark on generations of MIT undergraduate students with his captivating, innovative, and thoughtful approach to teaching.”

Mariana Gomez de Campo ’20 concurs: “There are certain professors that make their mark on students’ lives; professor Gabrieli permanently altered the course of mine.”

Laura Schulz, MacVicar Fellow and associate department head of brain and cognitive sciences, remarks, “His approach is visionary … John’s manner with students is unfailingly gracious … he hastens to remind them that they are as good as it gets, the smartest and brightest of their generation … it is the kind of warm, welcoming, inclusive approach to teaching that subtly but effectively reminds students that they belong here at MIT … It is little wonder that they love him.”

Marah Gubar

Marah Gubar joined MIT as an associate professor of literature in 2014. She received her BA in English literature from the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor and a PhD from Princeton University. Gubar taught in the English department at the University of Pittsburgh and served as director of the Children’s Literature Program. She received MIT’s James A. and Ruth Levitan Teaching Award in 2019 and the Teaching with Digital Technology Award in 2020.

Gubar’s research focuses on children’s literature, history of children’s theater, performance, and 19th- and 20th-century representations of childhood. Her research and pedagogies underscore the importance of integrated learning.

Colleagues at MIT note her efficacy in introducing new concepts and new subjects into the literature curriculum during her tenure as curricular chair. Gubar set the stage for wide-ranging curricular improvements, resulting in a host of literature subjects on interrelated topics within and across disciplines.

Gubar teaches several classes, including 21L.452 (Literature and Philosophy) and 21L.500 (How We Got to Hamilton). Her lectures provide uniquely enriching learning experiences in which her students are encouraged to dive into literary texts; craft thoughtful, persuasive arguments; and engage in lively intellectual debate.

Gubar encourages others to bring fresh ideas and think outside the box. For example, her seminar on “Hamilton” challenges students to recontextualize the hip-hop musical in several intellectual traditions. Professor Eric Klopfer, head of the Comparative Media Studies Program/Writing and interim head of literature, calls Gubar “a thoughtful, caring instructor, and course designer … She thinks critically about whose story is being told and by whom.”

MacVicar Fellow and professor of literature Stephen Tapscott praises her experimentation, abstract thinking, and storytelling: “Professor Gubar’s ability to frame intellectual questions in terms of problems, developments, and performance is an important dimension of the genius of her teaching.”

“Marah is hands-down the most enthusiastic, effective, and engaged professor I had the pleasure of learning from at MIT,” writes one student. “She’s one of the few instructors I’ve had who never feels the need to reassert her place in the didactic hierarchy, but approaches her students as intellectual equals.”

Tapscott continues, “She welcomes participation in ways that enrich the conversation, open new modes of communication, and empower students as autonomous literary critics. In professor Gubar’s classroom we learn by doing … and that progress also includes ‘doing’ textual analysis, cultural history, and abstract literary theory.”

Gubar is also a committed mentor and student testimonials highlight her supportive approach. One of her former students remarked that Gubar “has a strong drive to be inclusive, and truly cares about ‘getting it right’ … her passion for literature and teaching, together with her drive for inclusivity, her ability to take accountability, and her compassion and empathy for her students, make [her] a truly remarkable teacher.”

On receiving this award Marah Gubar writes, “The best word I can think of to describe how I reacted to hearing that I had received this very overwhelming honor is ‘plotzing.’ The Yiddish verb ‘to plotz’ literally means to crack, burst, or collapse, so that captures how undone I was. I started to cry, because it suddenly struck me how much joy my father, Edward Gubar, would have taken in this amazing news. He was a teacher, too, and he died during the first phase of this terrible pandemic that we’re still struggling to get through.”

Adam C. Martin

Adam C. Martin is a professor and undergraduate officer in the Department of Biology. He studies the molecular mechanisms that underlie tissue form and function. His research interests include gastrulation, embryotic development, cytoskeletal dynamics, and the coordination of cellular behavior. Martin received his PhD from the University of California at Berkeley and his BS in biology (genetics) from Cornell University. Martin joined the Course 7 faculty in 2011.

“I am overwhelmed with gratitude knowing that this has come from our students. The fact that they spent time to contribute to a nomination is incredibly meaningful to me,” says Martin. “I want to also thank all of my faculty colleagues with whom I have taught, appreciate, and learned immensely from over the past 12 years. I am a better teacher because of them and inspired by their dedication.”

He is committed to undergraduate education, teaching several key department offerings including 7.06 (Cell Biology), 7.016 (Introductory Biology), 7.002 (Fundamentals of Experimental Molecular Biology), and 7.102 (Introduction to Molecular Biology Techniques).

Martin’s style combines academic and scientific expertise with creative elements like props and demonstrations. His “energy and passion for the material” is obvious, writes Iain Cheeseman, associate department head and the Herman and Margaret Sokol Professor of Biology. “In addition to creating engaging lectures, Adam went beyond the standard classroom requirements to develop videos and animations (in collaboration with the Biology MITx team) to illustrate core cell biological approaches and concepts.”

What sets Martin apart is his connection with students, his positive spirit, and his welcoming demeanor. Apolonia Gardner ’22 reflects on the way he helped her outside of class through his running group, which connects younger students with seniors in his lab. “Professor Martin was literally committed to ‘going the extra mile’ by inviting his students to join him on runs around the Charles River on Friday afternoons,” she says.

Amy Keating, department head and Jay A. Stein professor of biology, and professor of biological engineering, goes on to praise Martin’s ability to attract students to Course 7 and guide them through their educational experience in his role as the director of undergraduate studies. “He hosts social events, presides at our undergraduate research symposium and the department’s undergraduate graduation and awards banquet, and works with the Biology Undergraduate Student Association,” she says.

As undergraduate officer, Martin is involved in both advising and curriculum building. He mentors UROP students, serves as a first-year advisor, and is a current member of MIT’s Committee on the Undergraduate Program (CUP).

Martin also brings a commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) as evidenced by his creation of a DEI journal club in his lab so that students have a dedicated space to discuss issues and challenges. Course 7 DEI officer Hallie Dowling-Huppert writes that Martin “thinks deeply about how DEI efforts are created to ensure that department members receive the maximum benefit. Adam considers all perspectives when making decisions, and is extremely empathetic and caring towards his students.”

“He makes our world so much better,” Keating observes. “Adam is a gem.”

Lawrence “Larry” Sass

Larry Sass SM ’94, PhD ’00 is an associate professor in the Department of Architecture. He earned his PhD and SM in architecture at MIT, and has a BArch from Pratt Institute in New York City. Sass joined the faculty in the Department of Architecture in 2002. His work focuses on the delivery of affordable housing for low-income families. He was included in an exhibit titled “Home Delivery: Fabricating the Modern Dwelling” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Sass’s teaching blends computation with design. His two signature courses, 4.500 (Design Computation: Art, Objects and Space) and 4.501 (Tiny Fab: Advancements in Rapid Design and Fabrication of Small Homes), reflect his specialization in digitally fabricating buildings and furniture from machines.

Professor and head of architecture Nicholas de Monchaux writes, “his classes provide crucial instruction and practice with 3D modeling and computer-generated rendering and animation … [He] links digital design to fabrication, in a process that invites students to define desirable design attributes of an object, develop a digital model, prototype it, and construct it at full scale.”

More generally, Sass’ approach is to help students build confidence in their own design process through hands-on projects. MIT Class of 1942 Professor John Ochsendorf, MacVicar Fellow, and founding director of the Morningside Academy for Design with appointments in the departments of architecture and civil and environmental engineering, confirms, “Larry’s teaching is a perfect embodiment of the ‘mens et manus’ spirit … [he] requires his students to go back and forth from mind and hand throughout each design project.”

Students say that his classes are a journey of self-discovery, allowing them to learn more about themselves and their own abilities. Senior Natasha Hirt notes, “What I learned from Larry was not something one can glean from a textbook, but a new way of seeing space … he tectonically shifted my perspective on buildings. He also shifted my perspective on myself. I’m a better designer for his teachings, and perhaps more importantly, I better understand how I design.”

Senior Izzi Waitz echoes this sentiment: “Larry emphasizes the importance of intentionally thinking through your designs and being confident in your choices … he challenges, questions, and prompts you so that you learn to defend and support yourself on your own.”

As a UROP coordinator, Sass assures students that the “sky is the limit” and all ideas are welcome. Postgraduate teaching fellow and research associate Myles Sampson says, “During the last year of my SM program, I assisted Larry in conducting a year-long UROP project … He structured the learning experience in a way that allowed the students to freely flex their design muscles: no idea was too outrageous.”

Sass is equally devoted to his students outside the classroom. In his role as head of house at MacGregor House, he lives in community with more than 300 undergraduates each year, providing academic guidance, creating residential programs and recreational activities, and ensuring that student wellness and mental health is a No. 1 priority.

Professor of architecture and MacVicar Fellow Les Norford says, “In two significant ways, Larry has been ahead of his time: combining digital representation and design with making and being alert to the well-being of his students.”

“In his kindness, he honors the memory of Margaret MacVicar, as well as the spirit of MIT itself,” Hirt concludes. “He is a designer, a craftsman, and an innovator. He is an inspiration and a compass.”

On receiving this award, Sass is full of excitement: “I love teaching and being part of the MIT community. I am grateful for the opportunity to be part of the MacVicar family of fellows.”