As part of our Ask the Brain series, science writer Shafaq Zia explores the question, “How are habits formed in the brain?”

____

Have you ever wondered why it is so hard to break free of bad habits like nail biting or obsessive social networking?

When we repeat an action over and over again, the behavioral pattern becomes automated in our brain, according to Jill R. Crittenden, molecular biologist and scientific advisor at McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT. For over a decade, Crittenden worked as a research scientist in the lab of Ann Graybiel, where one of the key questions scientists are working to answer is, how are habits formed?

Making habits

To understand how certain actions get wired in our neural pathways, this team of McGovern researchers experimented with rats, who were trained to run down a maze to receive a reward. If they turned left, they would get rich chocolate milk and for turning right, only sugar water. With this, the scientists wanted to see whether these animals could “learn to associate a cue with which direction they should turn in the maze in order to get the chocolate milk reward.”

Over time, the rats grew extremely habitual in their behavior; “they always turned the the correct direction and the places where their paws touched, in a fairly long maze, were exactly the same every time,” said Crittenden.

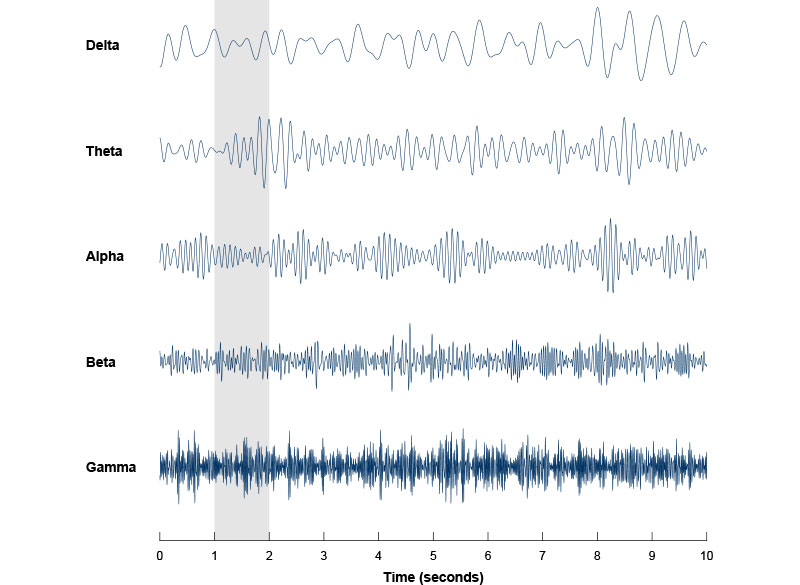

This isn’t a coincidence. When we’re first learning to do something, the frontal lobe and basal ganglia of the brain are highly active and doing a lot of calculations. These brain regions work together to associate behaviors with thoughts, emotions, and, most importantly, motor movements. But when we repeat an action over and over again, like the rats running down the maze, our brains become more efficient and fewer neurons are required to achieve the goal. This means, the more you do something, the easier it gets to carry it out because the behavior becomes literally etched in our brain as our motor movements.

But habits are complicated and they come in many different flavors, according to Crittenden. “I think we don’t have a great handle on how the differences [in our many habits] are separable neurobiologically, and so people argue a lot about how do you know that something’s a habit.”

The easiest way for scientists to test this in rodents is to see if the animal engages in the behavior even in the absence of reward. In this particular experiment, the researchers take away the reward, chocolate milk, to see whether the rats continue to run down the maze correctly. And to take it even a step further, they mix the chocolate milk with lithium chloride, which would upset the rat’s stomach. Despite all this, the rats continue to run down the maze and turn left towards the chocolate milk, as they had learnt to do over and over again.

Breaking habits

So does that mean once a habit is formed, it is impossible to shake it? Not quite. But it is tough. Rewards are a key building block to forming habits because our dopamine levels surge when we learn that an action is unexpectedly rewarded. For example, when the rats first learn to run down the maze, they’re motivated to receive the chocolate milk.

But things get complicated once the habit is formed. Researchers have found that this dopamine surge in response to reward ceases after a behavior becomes a habit. Instead the brain begins to release dopamine at the first cue or action that was previously learned to lead to the reward, so we are motivated to engage in the full behavioral sequence anyway, even if the reward isn’t there anymore.

This means we don’t have as much self-control as we think we do, which may also be the reason why it’s so hard to break the cycle of addiction. “People will report that they know this is bad for them. They don’t want it. And nevertheless, they select that action,” said Crittenden.

One common method to break the behavior, in this case, is called extinction. This is where psychologists try to weaken the association between the cue and the reward that led to habit formation in the first place. For example, if the rat no longer associates the cue to run down the maze with a reward, it will stop engaging in that behavior.

So the next time you beat yourself up over being unable to stick to a diet or sleep at a certain time, give yourself some grace and know that with consistency, a new, healthier habit can be born.