Last year, researchers at MIT’s McGovern Institute discovered and characterized Cas7-11, the first CRISPR enzyme capable of making precise, guided cuts to strands of RNA without harming cells in the process. Now, working with collaborators at the University of Tokyo, the same team has revealed that Cas7-11 can be shrunk to a more compact version, making it an even more viable option for editing the RNA inside living cells. The new, compact Cas7-11 was described today in the journal Cell along with a detailed structural analysis of the original enzyme.

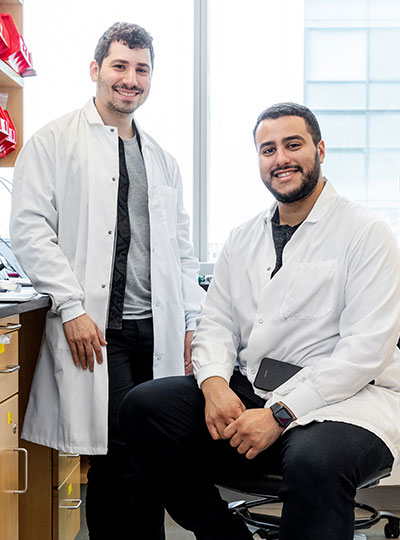

“When we looked at the structure, it was clear there were some pieces that weren’t needed which we could actually remove,” says McGovern Fellow Omar Abudayyeh, who led the new work with McGovern Fellow Jonathan Gootenberg and collaborator Hiroshi Nishimasu from the University of Tokyo. “This makes the enzyme small enough that it fits into a single viral vector for therapeutic applications.”

The authors, who also include postdoctoral researcher Nathan Zhou from the McGovern Institute and Kazuki Kato from the University Tokyo, see the new three-dimensional structure of Cas7-11 as a rich resource toanswer questions about the basic biology of the enzymes and reveal other ways to tweak its function in the future.

Targeting RNA

Over the past decade, the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technology has given researchers the ability to modify the genes inside human cells—a boon for both basic research and the development of therapeutics to reverse disease-causing genetic mutations. But CRISPR-Cas9 only works to alter DNA, and for some research and clinical purposes, editing RNA is more effective or useful.

A cell retains its DNA for life, and passes an identical copy to daughter cells as it duplicates, so any changes to DNA are relatively permanent. However, RNA is a more transient molecule, transcribed from DNA and degraded not long after.

“There are lots of positives about being able to permanently change DNA, especially when it comes to treating an inherited genetic disease,” Gootenberg says. “But for an infection, an injury or some other temporary disease, being able to temporarily modify a gene through RNA targeting makes more sense.”

Until Abudayyeh, Gootenberg and their colleagues discovered and characterized Cas7-11, the only enzyme that could target RNA had a messy side effect; when it recognized a particular gene, the enzyme—Cas13—began cutting up all the RNA around it. This property makes Cas13 effective for diagnostic tests, where it is used to detect the presence of a piece of RNA, but not very useful for therapeutics, where targeted cuts are required.

The discovery of Cas7-11 opened the doors to a more precise form of RNA editing, analogous to the Cas9 enzyme for DNA. However, the massive Cas7-11 protein was too big to fit inside a single viral vector—the empty shell of a virus that researchers typically use to deliver gene editing machinery into patient’s cells.

Structural insight

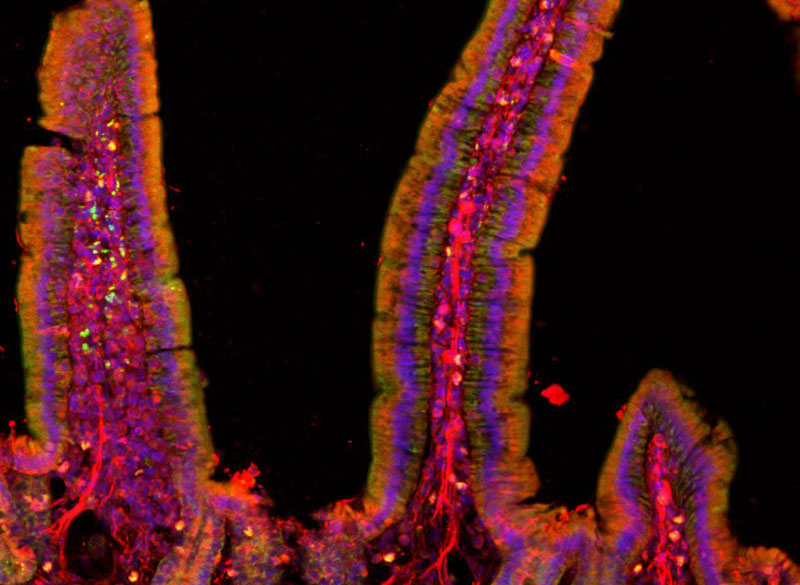

To determine the overall structure of Cas7-11, Abudayyeh, Gootenberg and Nishimasu used cryo-electron microscopy, which shines beams of electrons on frozen protein samples and measures how the beams are transmitted. The researchers knew that Cas7-11 was like an amalgamation of five separate Cas enzymes, fused into one single gene, but were not sure exactly how those parts folded and fit together.

“The really fascinating thing about Cas7-11, from a fundamental biology perspective, is that it should be all these separate pieces that come together, but instead you have a fusion into one gene,” Gootenberg says. “We really didn’t know what that would look like.”

The structure of Cas7-11, caught in the act of binding both its target tRNA strand and the guide RNA, which directs that binding, revealed how the pieces assembled and which parts of the protein were critical to recognizing and cutting RNA. This kind of structural insight is critical to figuring out how to make Cas7-11 carry out targeted jobs inside human cells.

The structure also illuminated a section of the protein that wasn’t serving any apparent functional role. This finding suggested the researchers could remove it, re-engineering Cas7-11 to make it smaller without taking away its ability to target RNA. Abudayyeh and Gootenberg tested the impact of removing different bits of this section, resulting in a new compact version of the protein, dubbed Cas7-11S. With Cas7-11S in hand, they packaged the system inside a single viral vector, delivered it into mammalian cells and efficiently targeted RNA.

The team is now planning future studies on other proteins that interact with Cas7-11 in the bacteria that it originates from, and also hopes to continue working towards the use of Cas7-11 for therapeutic applications.

“Imagine you could have an RNA gene therapy, and when you take it, it modifies your RNA, but when you stop taking it, that modification stops,” Abudayyeh says. “This is really just the beginning of enabling that tool set.”

This research was funded, in part, by the McGovern Institute Neurotechnology Program, K. Lisa Yang and Hock E. Tan Center for Molecular Therapeutics in Neuroscience, G. Harold & Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation, MIT John W. Jarve (1978) Seed Fund for Science Innovation, FastGrants, Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research Program, JSPS KAKENHI, Takeda Medical Research Foundation, and Inamori Research Institute for Science.