Scientists at Harvard University, the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and MIT have developed a technology to investigate the function of many different genes in many different cell types at once, in a living organism. They applied the large-scale method to study dozens of genes that are associated with autism spectrum disorder, identifying how specific cell types in the developing mouse brain are impacted by mutations.

The “Perturb-Seq” method, published in the journal Science, is an efficient way to identify potential biological mechanisms underlying autism spectrum disorder, which is an important first step toward developing treatments for the complex disease. The method is also broadly applicable to other organs, enabling scientists to better understand a wide range of disease and normal processes.

“For many years, genetic studies have identified a multitude of risk genes that are associated with the development of autism spectrum disorder. The challenge in the field has been to make the connection between knowing what the genes are, to understanding how the genes actually affect cells and ultimately behavior,” said co-senior author Paola Arlotta, the Golub Family Professor of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology at Harvard. “We applied the Perturb-Seq technology to an intact developing organism for the first time, showing the potential of measuring gene function at scale to better understand a complex disorder.”

The study was also led by co-senior authors Aviv Regev, who was a core member of the Broad Institute during the study and is currently Executive Vice President of Genentech Research and Early Development, and Feng Zhang, a core member of the Broad Institute and an investigator at MIT’s McGovern Institute.

To investigate gene function at a large scale, the researchers combined two powerful genomic technologies. They used CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to make precise changes, or perturbations, in 35 different genes linked to autism spectrum disorder risk. Then, they analyzed changes in the developing mouse brain using single-cell RNA sequencing, which allowed them to see how gene expression changed in over 40,000 individual cells.

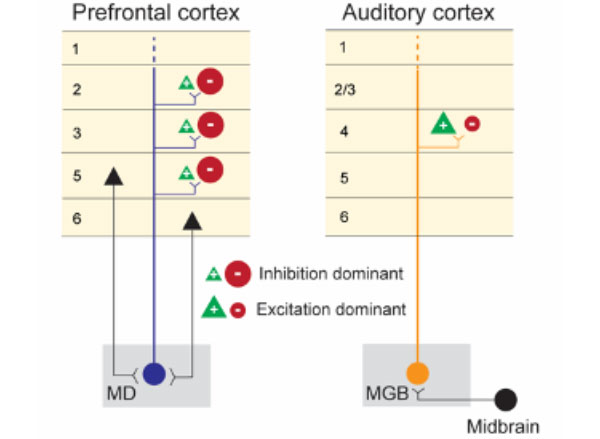

By looking at the level of individual cells, the researchers could compare how the risk genes affected different cell types in the cortex — the part of the brain responsible for complex functions including cognition and sensation. They analyzed networks of risk genes together to find common effects.

“We found that both neurons and glia — the non-neuronal cells in the brain — are directly affected by different sets of these risk genes,” said Xin Jin, lead author of the study and a Junior Fellow of the Harvard Society of Fellows. “Genes and molecules don’t generate cognition per se — they need to impact specific cell types in the brain to do so. We are interested in understanding how these different cell types can contribute to the disorder.”

To get a sense of the model’s potential relevance to the disorder in humans, the researchers compared their results to data from post-mortem human brains. In general, they found that in the post-mortem human brains with autism spectrum disorder, some of the key genes with altered expression were also affected in the Perturb-seq data.

“We now have a really rich dataset that allows us to draw insights, and we’re still learning a lot about it every day,” Jin said. “As we move forward with studying disease mechanisms in more depth, we can focus on the cell types that may be really important.”

“The field has been limited by the sheer time and effort that it takes to make one model at a time to test the function of single genes. Now, we have shown the potential of studying gene function in a developing organism in a scalable way, which is an exciting first step to understanding the mechanisms that lead to autism spectrum disorder and other complex psychiatric conditions, and to eventually develop treatments for these devastating conditions,” said Arlotta, who is also an institute member of the Broad Institute and part of the Broad’s Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research. “Our work also paves the way for Perturb-Seq to be applied to organs beyond the brain, to enable scientists to better understand the development or function of different tissue types, as well as pathological conditions.”

“Through genome sequencing efforts, a very large number of genes have been identified that, when mutated, are associated with human diseases. Traditionally, understanding the role of these genes would involve in-depth studies of each gene individually. By developing Perturb-seq for in vivo applications, we can start to screen all of these genes in animal models in a much more efficient manner, enabling us to understand mechanistically how mutations in these genes can lead to disease,” said Zhang, who is also the James and Patricia Poitras Professor of Neuroscience at MIT and a professor of brain and cognitive sciences and biological engineering at MIT.

This study was funded by the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation’s NARSAD Young Investigator Grant, Harvard University’s William F. Milton Fund, the Klarman Cell Observatory, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, a Center for Cell Circuits grant from the National Human Genome Research Institute’s Centers of Excellence in Genomic Science, the New York Stem Cell Foundation, the Mathers Foundation, the Poitras Center for Psychiatric Disorders Research at MIT, the Hock E. Tan and K. Lisa Yang Center for Autism Research at MIT, and J. and P. Poitras.