Social anxiety is usually treated with either cognitive behavioral therapy or medications. However, it is currently impossible to predict which treatment will work best for a particular patient. The team of researchers from MIT, Boston University (BU) and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) found that the effectiveness of therapy could be predicted by measuring patients’ brain activity as they looked at photos of faces, before the therapy sessions began.

The findings, published this week in the Archives of General Psychiatry, may help doctors more accurately choose treatments for social anxiety disorder, which is estimated to affect around 15 million people in the United States.

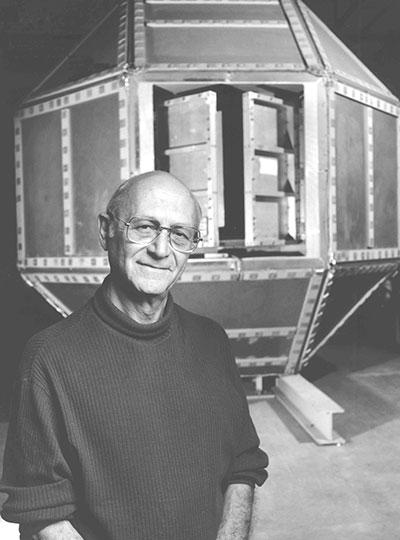

“Our vision is that some of these measures might direct individuals to treatments that are more likely to work for them,” says John Gabrieli, the Grover M. Hermann Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT, a member of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research and senior author of the paper.

Lead authors of the paper are MIT postdoc Oliver Doehrmann and Satrajit Ghosh, a research scientist in the McGovern Institute.

Choosing treatments

Sufferers of social anxiety disorder experience intense fear in social situations, interfering with their ability to function in daily life. Cognitive behavioral therapy aims to change the thought and behavior patterns that lead to anxiety. For social anxiety disorder patients, that might include learning to reverse the belief that others are watching or judging them.

The new paper is part of a larger study that MGH and BU recently ran on cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety, led by Mark Pollack, director of the Center for Anxiety and Traumatic Stress Disorders at MGH, and Stefan Hofmann, director of the Social Anxiety Program at BU.

“This was a chance to ask if these brain measures, taken before treatment, would be informative in ways above and beyond what physicians can measure now, and determine who would be responsive to this treatment,” Gabrieli says.

Currently doctors might choose a treatment based on factors such as ease of taking pills versus going to therapy, the possibility of drug side effects, or what the patients’ insurance will cover. “From a science perspective there’s very little evidence about which treatment is optimal for a person,” Gabrieli says.

The researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to image the brains of patients before and after treatment. There have been many imaging studies showing brain differences between healthy people and patients with neuropsychiatric disorders, but so far imaging has not been established as a way to predict patient response to particular treatments.

Measuring brain activity

In the new study, the researchers measured differences in brain activity as patients looked at images of angry or neutral faces. After 12 weeks of cognitive behavioral therapy, patients’ social anxiety levels were tested. The researchers found that patients who had shown a greater difference in activity in high-level visual processing areas during the face-response task showed the most improvement after therapy.

The findings are an important step towards improving doctors’ ability to choose the right treatment for psychiatric disorders, says Greg Siegle, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. “It’s really critical that somebody do this work, and they did it very well,” says Siegle, who was not part of the research team. “It moves the field forward, and brings psychology into more of a rigorous science, using neuroscience to distinguish between clinical cases that at first appear homogeneous.”

Gabrieli says it’s unclear why activity in brain regions involved with visual processing would be a good predictor of treatment outcome. One possibility is that patients who benefited more were those whose brains were already adept at segregating different types of experiences, Gabrieli says.

The researchers are now planning a follow-up study to investigate whether brain scans can predict differences in response between cognitive behavioral therapy and drug treatment.

“Right now, all by itself, we’re just giving somebody encouraging or discouraging news about the likely outcome of therapy,” Gabrieli says. “The really valuable thing would be if it turns out to be differentially sensitive to different treatment choices.”

The research was funded by the Poitras Center for Affective Disorders Research and the National Institute of Mental Health.