Two MIT neuroscientists have received grants from the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Foundation to screen for genes that could help brain cells withstand Parkinson’s disease and to map how gene expression changes in the brain in response to drugs of abuse.

Myriam Heiman, an associate professor in MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and a core member of the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and Alan Jasanoff, who is also a professor in biological engineering, brain and cognitive sciences, nuclear science and engineering and an associate investigator at the McGovern Institute for Brain Research, each received three-year awards that formally begin January 1, 2021.

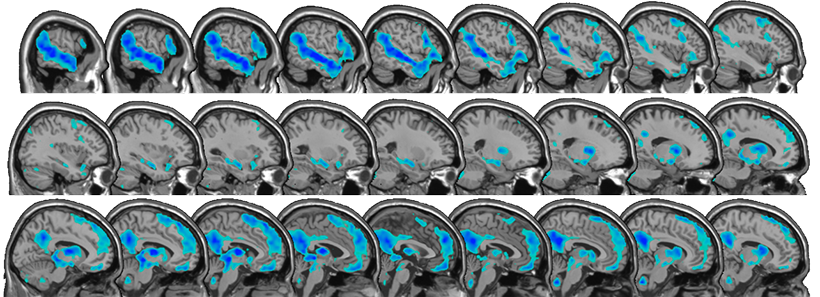

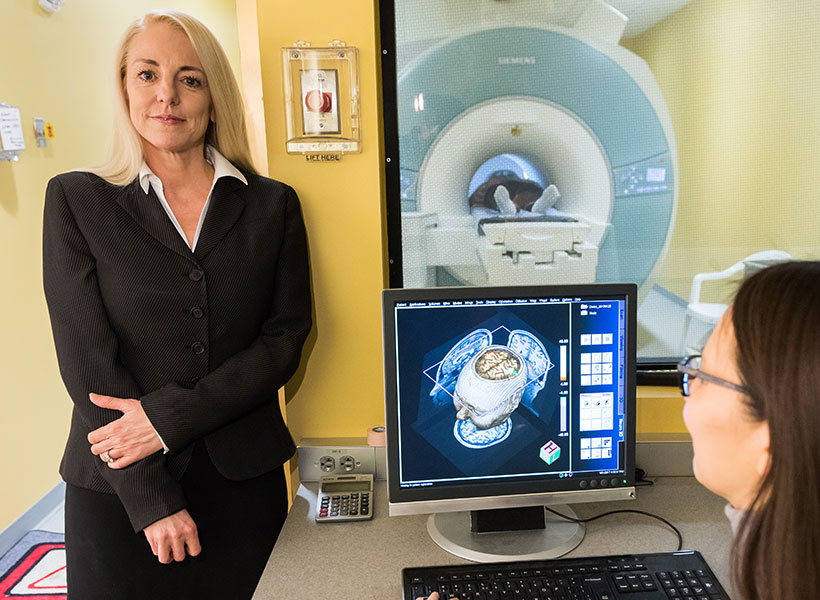

Jasanoff, who also directs MIT’s Center for Neurobiological Engineering, is known for developing sensors that monitor molecular hallmarks of neural activity in the living brain, in real time, via noninvasive MRI brain scanning. One of the MRI-detectable sensors that he has developed is for dopamine, a neuromodulator that is key to learning what behaviors and contexts lead to reward. Addictive drugs artificially drive dopamine release, thereby hijacking the brain’s reward prediction system. Studies have shown that dopamine and drugs of abuse activate gene transcription in specific brain regions, and that this gene expression changes as animals are repeatedly exposed to drugs. Despite the important implications of these neuroplastic changes for the process of addiction, in which drug-seeking behaviors become compulsive, there are no effective tools available to measure gene expression across the brain in real time.

Image: Alan Jasanoff

With the new Mathers funding, Jasanoff is developing new MRI-detectable sensors for gene expression. With these cutting-edge tools, Jasanoff proposes to make an activity atlas of how the brain responds to drugs of abuse, both upon initial exposure and over repeated doses that simulate the experiences of drug addicted individuals.

“Our studies will relate drug-induced brain activity to longer term changes that reshape the brain in addiction,” says Jasanoff. “We hope these studies will suggest new biomarkers or treatments.”

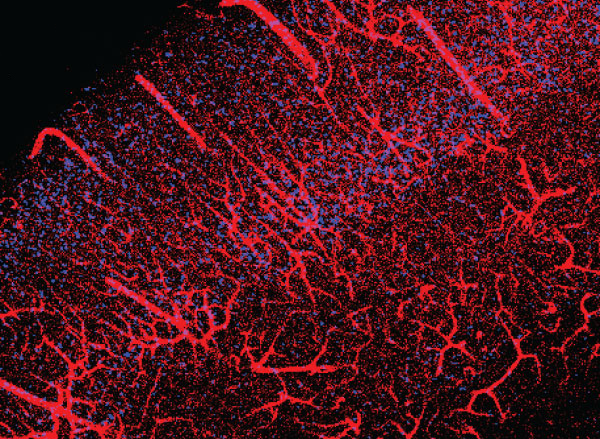

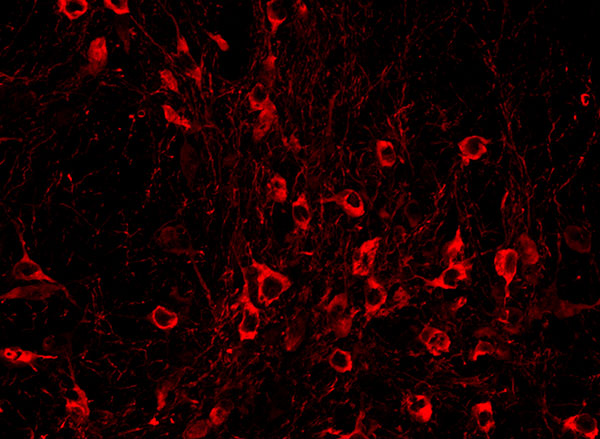

Dopamine-producing neurons in a brain region called the substantia nigra are known to be especially vulnerable to dying in Parkinson’s disease, leading to the severe motor difficulties experienced during the progression of the incurable, chronic neurodegenerative disorder. The field knows little about what puts specific cells at such dire risk, or what molecular mechanisms might help them resist the disease. In her research on Huntington’s disease, another incurable neurodegenerative disorder in which a specific neuron population in the striatum is especially vulnerable, Heiman has been able to use an innovative method her lab pioneered to discover genes whose expression promotes neuron survival, yielding potential new drug targets. The technique involves conducting an unbiased screen in which her lab knocks out each of the 22,000 genes expressed in the mouse brain one by one in neurons in disease model mice and healthy controls. The technique allows her to determine which genes, when missing, contribute to neuron death amid disease and therefore which genes are particularly needed for survival. The products of those genes can then be evaluated as drug targets. With the new Mathers award, Heiman plans to apply the method to study Parkinson’s disease.

“There is currently no molecular explanation for the brain cell loss seen in Parkinson’s disease or a cure for this devastating disease,” Heiman said. “This award will allow us to perform unbiased, genome-wide genetic screens in the brains of mouse models of Parkinson’s disease, probing for genes that allow brain cells to survive the effects of cellular perturbations associated with Parkinson’s disease. I’m extremely grateful for this generous support and recognition of our work from the Mathers Foundation, and hope that our study will elucidate new therapeutic targets for the treatment and even prevention of Parkinson’s disease.”