This story originally appeared in the Winter 2022 issue of BrainScan.

***

For people struggling with substance use disorders — and there are about 35 million of them worldwide — treatment options are limited. Even among those who seek help, relapse is common. In the United States, an epidemic of opioid addiction has been declared a public health emergency.

A 2019 survey found that 1.6 million people nationwide had an opioid use disorder, and the crisis has surged since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that more than 100,000 people died of drug overdose between April 2020 and April 2021 — nearly 30 percent more overdose deaths than occurred during the same period the previous year.

In the United States, an epidemic of opioid addiction has been declared a public health emergency.

A deeper understanding of what addiction does to the brain and body is urgently needed to pave the way to interventions that reliably release affected individuals from its grip. At the McGovern Institute, researchers are turning their attention to addiction’s driving force: the deep, recurring craving that makes people prioritize drug use over all other wants and needs.

“When you are in that state, then it seems nothing else matters,” says McGovern Investigator Fan Wang. “At that moment, you can discard everything: your relationship, your house, your job, everything. You only want the drug.”

With a new addiction initiative catalyzed by generous gifts from Institute co-founder Lore Harp McGovern and others, McGovern scientists with diverse expertise have come together to begin clarifying the neurobiology that underlies the craving state. They plan to dissect the neural transformations associated with craving at every level — from the drug-induced chemical changes that alter neuronal connections and activity to how these modifications impact signaling brain-wide. Ultimately, the McGovern team hopes not just to understand the craving state, but to find a way to relieve it — for good.

“If we can understand the craving state and correct it, or at least relieve a little bit of the pressure,” explains Wang, who will help lead the addiction initiative, “then maybe we can at least give people a chance to use their top-down control to not take the drug.”

The craving cycle

For individuals suffering from substance use disorders, craving fuels a cyclical pattern of escalating drug use. Following the euphoria induced by a drug like heroin or cocaine, depression sets in, accompanied by a drug craving motivated by the desire to relieve that suffering. And as addiction progresses, the peaks and valleys of this cycle dip lower: the pleasant feelings evoked by the drug become weaker, while the negative effects a person experiences in its absence worsen. The craving remains, and increasing use of the drug are required to relieve it.

By the time addiction sets in, the brain has been altered in ways that go beyond a drug’s immediate effects on neural signaling.

These insidious changes leave individuals susceptible to craving — and the vulnerable state endures. Long after the physical effects of withdrawal have subsided, people with substance use disorders can find their craving returns, triggered by exposure to a small amount of the drug, physical or social cues associated with previous drug use, or stress. So researchers will need to determine not only how different parts of the brain interact with one another during craving and how individual cells and the molecules within them are affected by the craving state — but also how things change as addiction develops and progresses.

Circuits, chemistry and connectivity

One clear starting point is the circuitry the brain uses to control motivation. Thanks in part to decades of research in the lab of McGovern Investigator Ann Graybiel, neuroscientists know a great deal about how these circuits learn which actions lead to pleasure and which lead to pain, and how they use that information to establish habits and evaluate the costs and benefits of complex decisions.

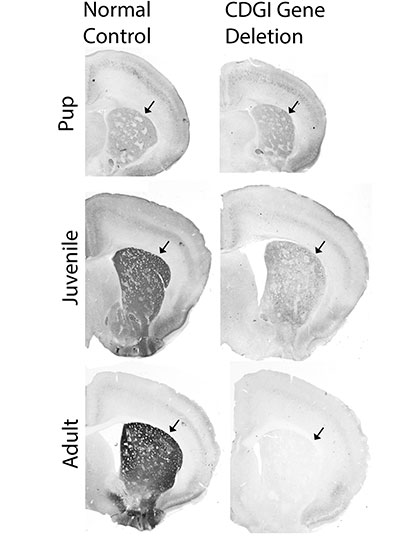

Graybiel’s work has shown that drugs of abuse strongly activate dopamine-responsive neurons in a part of the brain called the striatum, whose signals promote habit formation. By increasing the amount of dopamine that neurons release, these drugs motivate users to prioritize repeated drug use over other kinds of rewards, and to choose the drug in spite of pain or other negative effects. Her group continues to investigate the naturally occurring molecules that control these circuits, as well as how they are hijacked by drugs of abuse.

In Fan Wang’s lab, work investigating the neural circuits that mediate the perception of physical pain has led her team to question the role of emotional pain in craving. As they investigated the source of pain sensations in the brain, they identified neurons in an emotion-regulating center called the central amygdala that appear to suppress physical pain in animals. Now, Wang wants to know whether it might be possible to modulate neurons involved in emotional pain to ameliorate the negative state that provokes drug craving.

These animal studies will be key to identifying the cellular and molecular changes that set the brain up for recurring cravings. And as McGovern scientists begin to investigate what happens in the brains of rodents that have been trained to self-administer addictive drugs like fentanyl or cocaine, they expect to encounter tremendous complexity.

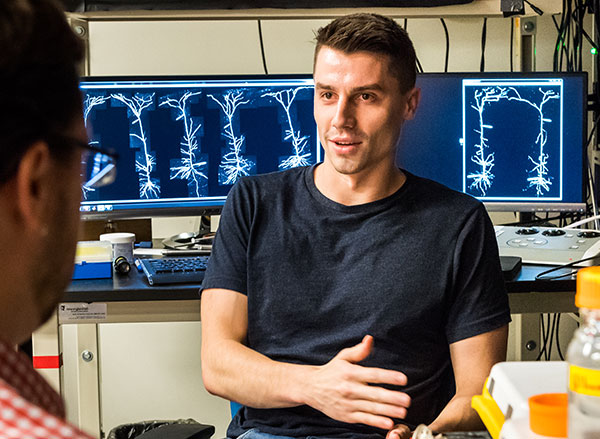

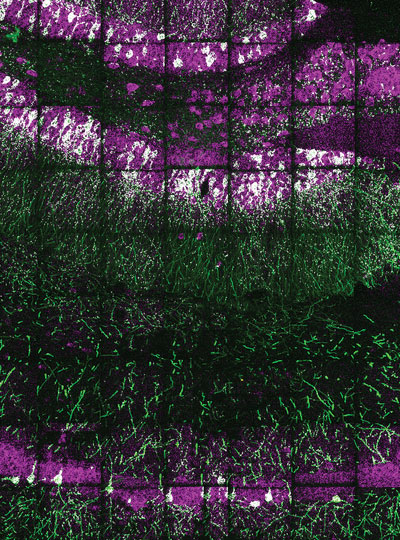

McGovern Associate Investigator Polina Anikeeva, whose lab has pioneered new technologies that will help the team investigate the full spectrum of changes that underlie craving, says it will be important to consider impacts on the brain’s chemistry, firing patterns, and connectivity. To that end, multifunctional research probes developed in her lab will be critical to monitoring and manipulating neural circuits in animal models.

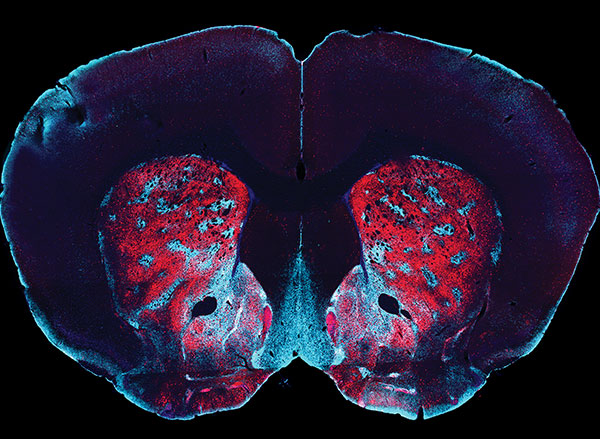

Imaging technology developed by investigator Ed Boyden will also enable nanoscale protein visualization brain-wide. An important goal will be to identify a neural signature of the craving state. With such a signal, researchers can begin to explore how to shut off that craving — possibly by directly modulating neural signaling.

Targeted treatments

“One of the reasons to study craving is because it’s a natural treatment point,” says McGovern Associate Investigator Alan Jasanoff. “And the dominant kind of approaches that people in our team think about are approaches that relate to neural circuits — to the specific connections between brain regions and how those could be changed.” The hope, he explains, is that it might be possible to identify a brain region whose activity is disrupted during the craving state, then use clinical brain stimulation methods to restore normal signaling — within that region, as well as in other connected parts of the brain.

To identify the right targets for such a treatment, it will be crucial to understand how the biology uncovered in laboratory animals reflects what’s happens in people with substance use disorders. Functional imaging in John Gabrieli’s lab can help bridge the gap between clinical and animal research by revealing patterns of brain activity associated with the craving state in both humans and rodents. A new technique developed in Jasanoff’s lab makes it possible to focus on the activity between specific regions of an animal’s brain. “By doing that, we hope to build up integrated models of how information passes around the brain in craving states, and of course also in control states where we’re not experiencing craving,” he explains.

In delving into the biology of the craving state, McGovern scientists are embarking on largely unexplored territory — and they do so with both optimism and urgency. “It’s hard to not appreciate just the size of the problem, and just how devastating addiction is,” says Anikeeva. “At this point, it just seems almost irresponsible to not work on it, especially when we do have the tools and we are interested in the general brain regions that are important for that problem. I would say that there’s almost a civic duty.”