As a young girl growing up in the former Soviet Union, Evelina Fedorenko PhD ’07 studied several languages, including English, as her mother hoped that it would give her the chance to eventually move abroad for better opportunities.

Her language studies not only helped her establish a new life in the United States as an adult, but also led to a lifelong interest in linguistics and how the brain processes language. Now an associate professor of brain and cognitive sciences at MIT, Fedorenko studies the brain’s language-processing regions: how they arise, whether they are shared with other mental functions, and how each region contributes to language comprehension and production.

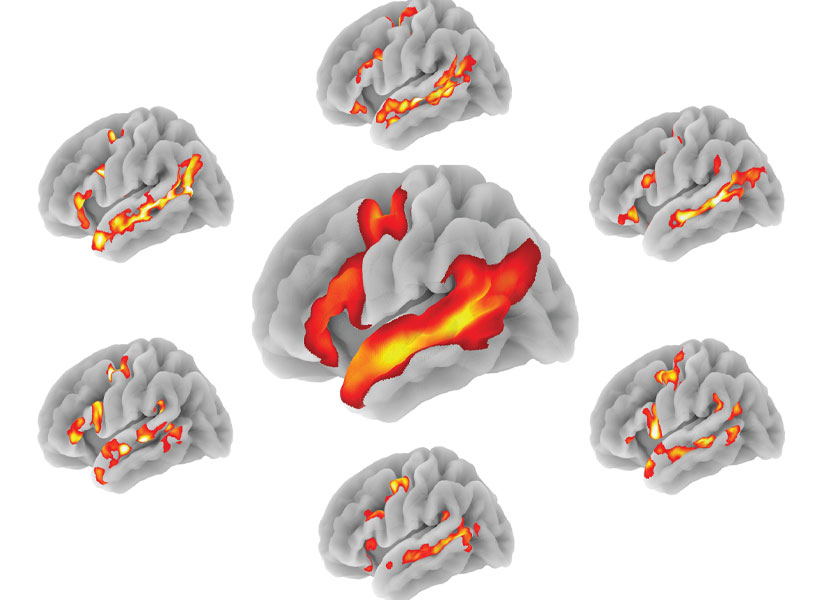

Fedorenko’s early work helped to identify the precise locations of the brain’s language-processing regions, and she has been building on that work to generate insight into how different neuronal populations in those regions implement linguistic computations.

“It took a while to develop the approach and figure out how to quickly and reliably find these regions in individual brains, given this standard problem of the brain being a little different across people,” she says. “Then we just kept going, asking questions like: Does language overlap with other functions that are similar to it? How is the system organized internally? Do different parts of this network do different things? There are dozens and dozens of questions you can ask, and many directions that we have pushed on.”

Among some of the more recent directions, she is exploring how the brain’s language-processing regions develop early in life, through studies of very young children, people with unusual brain architecture, and computational models known as large language models.

From Russia to MIT

Fedorenko grew up in the Russian city of Volgograd, which was then part of the Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union broke up in 1991, her mother, a mechanical engineer, lost her job, and the family struggled to make ends meet.

“It was a really intense and painful time,” Fedorenko recalls. “But one thing that was always very stable for me is that I always had a lot of love, from my parents, my grandparents, and my aunt and uncle. That was really important and gave me the confidence that if I worked hard and had a goal, that I could achieve whatever I dreamed about.”

Fedorenko did work hard in school, studying English, French, German, Polish, and Spanish, and she also participated in math competitions. As a 15-year-old, she spent a year attending high school in Alabama, as part of a program that placed students from the former Soviet Union with American families. She had been thinking about applying to universities in Europe but changed her plans when she realized the American higher education system offered more academic flexibility.

After being admitted to Harvard University with a full scholarship, she returned to the United States in 1998 and earned her bachelor’s degree in psychology and linguistics, while also working multiple jobs to send money home to help her family.

While at Harvard, she also took classes at MIT and ended up deciding to apply to the Institute for graduate school. For her PhD research at MIT, she worked with Ted Gibson, a professor of brain and cognitive sciences, and later, Nancy Kanwisher, the Walter A. Rosenblith Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience. She began by using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to study brain regions that appeared to respond preferentially to music, but she soon switched to studying brain responses to language.

She found that working with Kanwisher, who studies the functional organization of the human brain but hadn’t worked much on language before, helped Fedorenko to build a research program free of potential biases baked into some of the early work on language processing in the brain.

“We really kind of started from scratch,” Fedorenko says, “combining the knowledge of language processing I have gained by working with Gibson and the rigorous neuroscience approaches that Kanwisher had developed when studying the visual system.”

After finishing her PhD in 2007, Fedorenko stayed at MIT for a few years as a postdoc funded by the National Institutes of Health, continuing her research with Kanwisher. During that time, she and Kanwisher developed techniques to identify language-processing regions in different people, and discovered new evidence that certain parts of the brain respond selectively to language. Fedorenko then spent five years as a research faculty member at Massachusetts General Hospital, before receiving an offer to join the faculty at MIT in 2019.

How the brain processes language

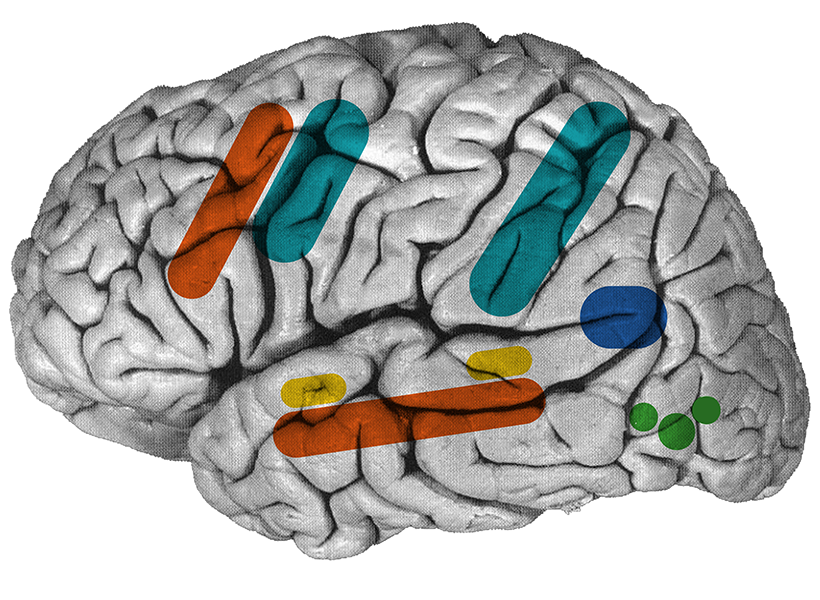

Since starting her lab at MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research, Fedorenko and her trainees have made several discoveries that have helped to refine neuroscientists’ understanding of the brain’s language-processing regions, which are spread across the left frontal and temporal lobes of the brain.

In a series of studies, her lab showed that these regions are highly selective for language and are not engaged by activities such as listening to music, reading computer code, or interpreting facial expressions, all of which have been argued to be share similarities with language processing.

“We’ve separated the language-processing machinery from various other systems, including the system for general fluid thinking, and the systems for social perception and reasoning, which support the processing of communicative signals, like facial expressions and gestures, and reasoning about others’ beliefs and desires,” Fedorenko says. “So that was a significant finding, that this system really is its own thing.”

More recently, Fedorenko has turned her attention to figuring out, in more detail, the functions of different parts of the language processing network. In one recent study, she identified distinct neuronal populations within these regions that appear to have different temporal windows for processing linguistic content, ranging from just one word up to six words.

She is also studying how language-processing circuits arise in the brain, with ongoing studies in which she and a postdoc in her lab are using fMRI to scan the brains of young children, observing how their language regions behave even before the children have fully learned to speak and understand language.

Large language models (similar to ChatGPT) can help with these types of developmental questions, as the researchers can better control the language inputs to the model and have continuous access to its abilities and representations at different stages of learning.

“You can train models in different ways, on different kinds of language, in different kind of regimens. For example, training on simpler language first and then more complex language, or on language combined with some visual inputs. Then you can look at the performance of these language models on different tasks, and also examine changes in their internal representations across the training trajectory, to test which model best captures the trajectory of human language learning,” Fedorenko says.

To gain another window into how the brain develops language ability, Fedorenko launched the Interesting Brains Project several years ago. Through this project, she is studying people who experienced some type of brain damage early in life, such as a prenatal stroke, or brain deformation as a result of a congenital cyst. In some of these individuals, their conditions destroyed or significantly deformed the brain’s typical language-processing areas, but all of these individuals are cognitively indistinguishable from individuals with typical brains: They still learned to speak and understand language normally, and in some cases, they didn’t even realize that their brains were in some way atypical until they were adults.

“That study is all about plasticity and redundancy in the brain, trying to figure out what brains can cope with, and how” Fedorenko says. “Are there many solutions to build a human mind, even when the neural infrastructure is so different-looking?”