Using this system, the researchers showed that they could deliver genes as long as 36,000 DNA base pairs to several types of human cells, as well as to liver cells in mice. The new technique, known as PASTE, could hold promise for treating diseases that are caused by defective genes with a large number of mutations, such as cystic fibrosis.

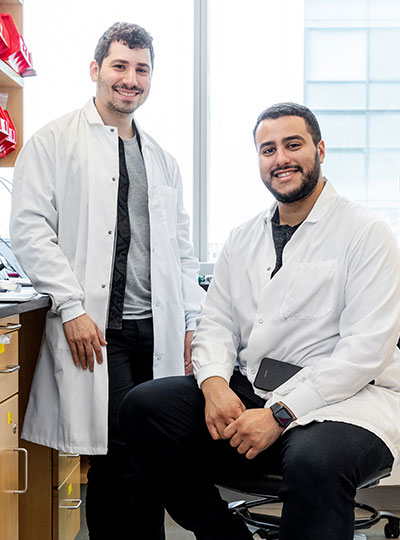

“It’s a new genetic way of potentially targeting these really hard to treat diseases,” says Omar Abudayyeh, a McGovern Fellow at MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research. “We wanted to work toward what gene therapy was supposed to do at its original inception, which is to replace genes, not just correct individual mutations.”

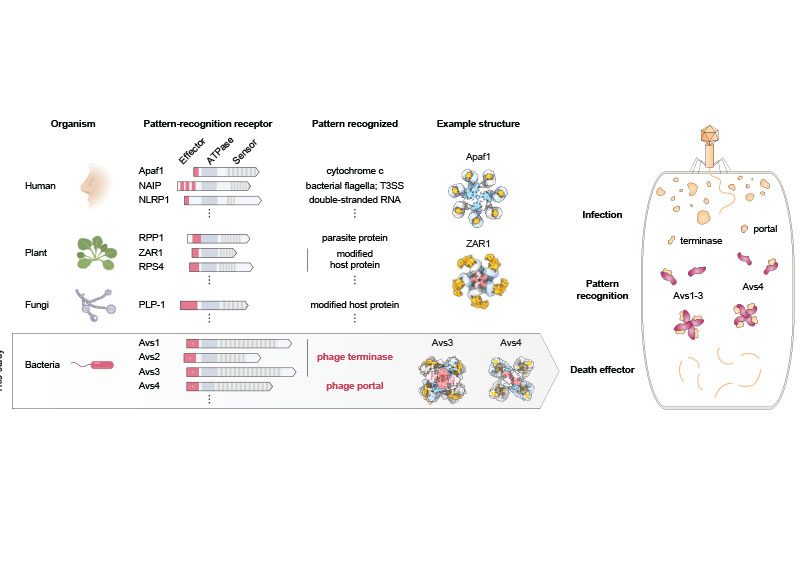

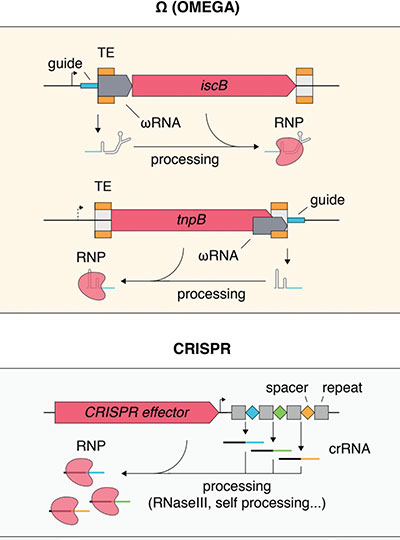

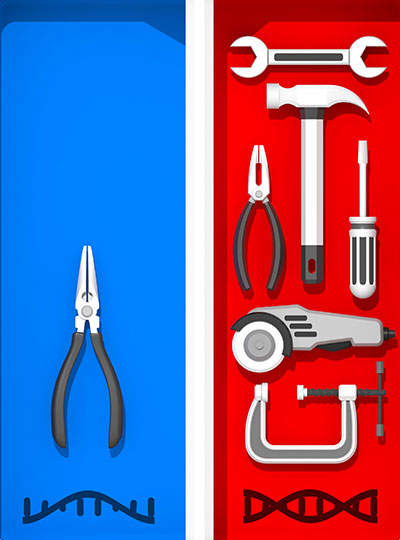

The new tool combines the precise targeting of CRISPR-Cas9, a set of molecules originally derived from bacterial defense systems, with enzymes called integrases, which viruses use to insert their own genetic material into a bacterial genome.

“Just like CRISPR, these integrases come from the ongoing battle between bacteria and the viruses that infect them,” says Jonathan Gootenberg, also a McGovern Fellow. “It speaks to how we can keep finding an abundance of interesting and useful new tools from these natural systems.”

Gootenberg and Abudayyeh are the senior authors of the new study, which appears today in Nature Biotechnology. The lead authors of the study are MIT technical associates Matthew Yarnall and Rohan Krajeski, former MIT graduate student Eleonora Ioannidi, and MIT graduate student Cian Schmitt-Ulms.

DNA insertion

The CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system consists of a DNA-cutting enzyme called Cas9 and a short RNA strand that guides the enzyme to a specific area of the genome, directing Cas9 where to make its cut. When Cas9 and the guide RNA targeting a disease gene are delivered into cells, a specific cut is made in the genome, and the cells’ DNA repair processes glue the cut back together, often deleting a small portion of the genome.

If a DNA template is also delivered, the cells can incorporate a corrected copy into their genomes during the repair process. However, this process requires cells to make double-stranded breaks in their DNA, which can cause chromosomal deletions or rearrangements that are harmful to cells. Another limitation is that it only works in cells that are dividing, as nondividing cells don’t have active DNA repair processes.

The MIT team wanted to develop a tool that could cut out a defective gene and replace it with a new one without inducing any double-stranded DNA breaks. To achieve this goal, they turned to a family of enzymes called integrases, which viruses called bacteriophages use to insert themselves into bacterial genomes.

For this study, the researchers focused on serine integrases, which can insert huge chunks of DNA, as large as 50,000 base pairs. These enzymes target specific genome sequences known as attachment sites, which function as “landing pads.” When they find the correct landing pad in the host genome, they bind to it and integrate their DNA payload.

In past work, scientists have found it challenging to develop these enzymes for human therapy because the landing pads are very specific, and it’s difficult to reprogram integrases to target other sites. The MIT team realized that combining these enzymes with a CRISPR-Cas9 system that inserts the correct landing site would enable easy reprogramming of the powerful insertion system.

The new tool, PASTE (Programmable Addition via Site-specific Targeting Elements), includes a Cas9 enzyme that cuts at a specific genomic site, guided by a strand of RNA that binds to that site. This allows them to target any site in the genome for insertion of the landing site, which contains 46 DNA base pairs. This insertion can be done without introducing any double-stranded breaks by adding one DNA strand first via a fused reverse transcriptase, then its complementary strand.

Once the landing site is incorporated, the integrase can come along and insert its much larger DNA payload into the genome at that site.

“We think that this is a large step toward achieving the dream of programmable insertion of DNA,” Gootenberg says. “It’s a technique that can be easily tailored both to the site that we want to integrate as well as the cargo.”

Gene replacement

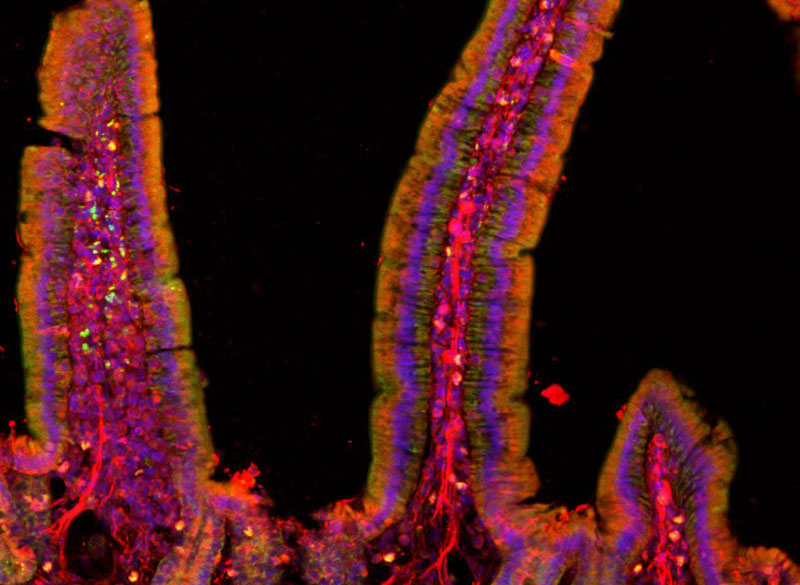

In this study, the researchers showed that they could use PASTE to insert genes into several types of human cells, including liver cells, T cells, and lymphoblasts (immature white blood cells). They tested the delivery system with 13 different payload genes, including some that could be therapeutically useful, and were able to insert them into nine different locations in the genome.

In these cells, the researchers were able to insert genes with a success rate ranging from 5 to 60 percent. This approach also yielded very few unwanted “indels” (insertions or deletions) at the sites of gene integration.

“We see very few indels, and because we’re not making double-stranded breaks, you don’t have to worry about chromosomal rearrangements or large-scale chromosome arm deletions,” Abudayyeh says.

The researchers also demonstrated that they could insert genes in “humanized” livers in mice. Livers in these mice consist of about 70 percent human hepatocytes, and PASTE successfully integrated new genes into about 2.5 percent of these cells.

The DNA sequences that the researchers inserted in this study were up to 36,000 base pairs long, but they believe even longer sequences could also be used. A human gene can range from a few hundred to more than 2 million base pairs, although for therapeutic purposes only the coding sequence of the protein needs to be used, drastically reducing the size of the DNA segment that needs to be inserted into the genome.

“The ability to site-specifically make large genomic integrations is of huge value to both basic science and biotechnology studies. This toolset will, I anticipate, be very enabling for the research community,” says Prashant Mali, a professor of bioengineering at the University of California at San Diego, who was not involved in the study.

The researchers are now further exploring the possibility of using this tool as a possible way to replace the defective cystic fibrosis gene. This technique could also be useful for treating blood diseases caused by faulty genes, such as hemophilia and G6PD deficiency, or Huntington’s disease, a neurological disorder caused by a defective gene that has too many gene repeats.

The researchers have also made their genetic constructs available online for other scientists to use.

“One of the fantastic things about engineering these molecular technologies is that people can build on them, develop and apply them in ways that maybe we didn’t think of or hadn’t considered,” Gootenberg says. “It’s really great to be part of that emerging community.”

The research was funded by a Swiss National Science Foundation Postdoc Mobility Fellowship, the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the McGovern Institute Neurotechnology Program, the K. Lisa Yang and Hock E. Tan Center for Molecular Therapeutics in Neuroscience, the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation, the MIT John W. Jarve Seed Fund for Science Innovation, Impetus Grants, a Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Pioneer Grant, Google Ventures, Fast Grants, the Harvey Family Foundation, and the McGovern Institute.