Unlike prostheses in which the residual limb sits within a socket, the new system is directly integrated with the user’s muscle and bone tissue. This enables greater stability and gives the user much more control over the movement of the prosthesis.

Participants in a small clinical study also reported that the limb felt more like a part of their own body, compared to people who had more traditional above-the-knee amputations.

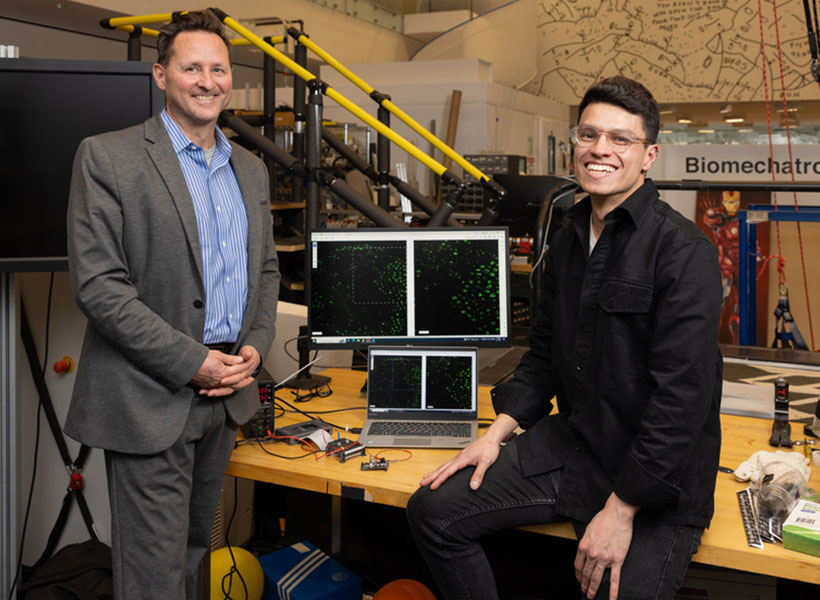

“A prosthesis that’s tissue-integrated — anchored to the bone and directly controlled by the nervous system — is not merely a lifeless, separate device, but rather a system that is carefully integrated into human physiology, offering a greater level of prosthetic embodiment. It’s not simply a tool that the human employs, but rather an integral part of self,” says Hugh Herr, a professor of media arts and sciences, co-director of the K. Lisa Yang Center for Bionics at MIT, an associate member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research, and the senior author of the new study.

Tony Shu PhD ’24 is the lead author of the paper, which appears today in Science.

Better control

Over the past several years, Herr’s lab has been working on new prostheses that can extract neural information from muscles left behind after an amputation and use that information to help guide a prosthetic limb.

During a traditional amputation, pairs of muscles that take turns stretching and contracting are usually severed, disrupting the normal agonist-antagonist relationship of the muscles. This disruption makes it very difficult for the nervous system to sense the position of a muscle and how fast it’s contracting.

Using the new surgical approach developed by Herr and his colleagues, known as agonist-antagonist myoneuronal interface (AMI), muscle pairs are reconnected during surgery so that they still dynamically communicate with each other within the residual limb. This sensory feedback helps the wearer of the prosthesis to decide how to move the limb, and also generates electrical signals that can be used to control the prosthetic limb.

In a 2024 study, the researchers showed that people with amputations below the knee who received the AMI surgery were able to walk faster and navigate around obstacles much more naturally than people with traditional below-the-knee amputations.

In the new study, the researchers extended the approach to better serve people with amputations above the knee. They wanted to create a system that could not only read out signals from the muscles using AMI but also be integrated into the bone, offering more stability and better sensory feedback.

To achieve that, the researchers developed a procedure to insert a titanium rod into the residual femur bone at the amputation site. This implant allows for better mechanical control and load bearing than a traditional prosthesis. Additionally, the implant contains 16 wires that collect information from electrodes located on the AMI muscles inside the body, which enables more accurate transduction of the signals coming from the muscles.

This bone-integrated system, known as e-OPRA, transmits AMI signals to a new robotic controller developed specifically for this study. The controller uses this information to calculate the torque necessary to move the prosthesis the way that the user wants it to move.

“All parts work together to better get information into and out of the body and better interface mechanically with the device,” Shu says. “We’re directly loading the skeleton, which is the part of the body that’s supposed to be loaded, as opposed to using sockets, which is uncomfortable and can lead to frequent skin infections.”

In this study, two subjects received the combined AMI and e-OPRA system, known as an osseointegrated mechanoneural prosthesis (OMP). These users were compared with eight who had the AMI surgery but not the e-OPRA implant, and seven users who had neither AMI nor e-OPRA. All subjects took a turn at using an experimental powered knee prosthesis developed by the lab.

The researchers measured the participants’ ability to perform several types of tasks, including bending the knee to a specified angle, climbing stairs, and stepping over obstacles. In most of these tasks, users with the OMP system performed better than the subjects who had the AMI surgery but not the e-OPRA implant, and much better than users of traditional prostheses.

“This paper represents the fulfillment of a vision that the scientific community has had for a long time — the implementation and demonstration of a fully physiologically integrated, volitionally controlled robotic leg,” says Michael Goldfarb, a professor of mechanical engineering and director of the Center for Intelligent Mechatronics at Vanderbilt University, who was not involved in the research. “This is really difficult work, and the authors deserve tremendous credit for their efforts in realizing such a challenging goal.”

A sense of embodiment

In addition to testing gait and other movements, the researchers also asked questions designed to evaluate participants’ sense of embodiment — that is, to what extent their prosthetic limb felt like a part of their own body.

Questions included whether the patients felt as if they had two legs, if they felt as if the prosthesis was part of their body, and if they felt in control of the prosthesis. Each question was designed to evaluate the participants’ feelings of agency, ownership of device, and body representation.

The researchers found that as the study went on, the two participants with the OMP showed much greater increases in their feelings of agency and ownership than the other subjects.

“Another reason this paper is significant is that it looks into these embodiment questions and it shows large improvements in that sensation of embodiment,” Herr says. “No matter how sophisticated you make the AI systems of a robotic prosthesis, it’s still going to feel like a tool to the user, like an external device. But with this tissue-integrated approach, when you ask the human user what is their body, the more it’s integrated, the more they’re going to say the prosthesis is actually part of self.”

The AMI procedure is now done routinely on patients with below-the-knee amputations at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Herr expects it will soon become the standard for above-the-knee amputations as well. The combined OMP system will need larger clinical trials to receive FDA approval for commercial use, which Herr expects may take about five years.

The research was funded by the Yang Tan Collective and DARPA.