Right now, this kind of comprehensive study is not possible because current techniques for imaging cells are limited to just a handful of different molecule types within a cell at one time. However, MIT researchers have developed an alternative method that allows them to observe up to seven different molecules at a time, and potentially even more than that.

“There are many examples in biology where an event triggers a long downstream cascade of events, which then causes a specific cellular function,” says Edward Boyden, the Y. Eva Tan Professor in Neurotechnology. “How does that occur? It’s arguably one of the fundamental problems of biology, and so we wondered, could you simply watch it happen?”

It’s arguably one of the fundamental problems of biology, and so we wondered, could you simply watch it happen? – Ed Boyden

The new approach makes use of green or red fluorescent molecules that flicker on and off at different rates. By imaging a cell over several seconds, minutes, or hours, and then extracting each of the fluorescent signals using a computational algorithm, the amount of each target protein can be tracked as it changes over time.

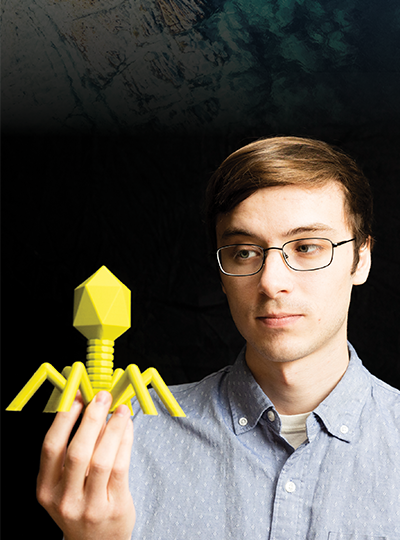

Boyden, who is also a professor of biological engineering and of brain and cognitive sciences at MIT, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, and a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research and Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, as well as the co-director of the K. Lisa Yang Center for Bionics, is the senior author of the study, which appears today in Cell. MIT postdoc Yong Qian is the lead author of the paper.

Fluorescent signals

Labeling molecules inside cells with fluorescent proteins has allowed researchers to learn a great deal about the functions of many cellular molecules. This type of study is often done with green fluorescent protein (GFP), which was first deployed for imaging in the 1990s. Since then, several fluorescent proteins that glow in other colors have been developed for experimental use.

However, a typical light microscope can only distinguish two or three of these colors, allowing researchers only a tiny glimpse of the overall activity that is happening inside a cell. If they could track a greater number of labeled molecules, researchers could measure a brain cell’s response to different neurotransmitters during learning, for example, or investigate the signals that prompt a cancer cell to metastasize.

“Ideally, you would be able to watch the signals in a cell as they fluctuate in real time, and then you could understand how they relate to each other. That would tell you how the cell computes,” Boyden says. “The problem is that you can’t watch very many things at the same time.”

In 2020, Boyden’s lab developed a way to simultaneously image up to five different molecules within a cell, by targeting glowing reporters to distinct locations inside the cell. This approach, known as “spatial multiplexing,” allows researchers to distinguish signals for different molecules even though they may all be fluorescing the same color.

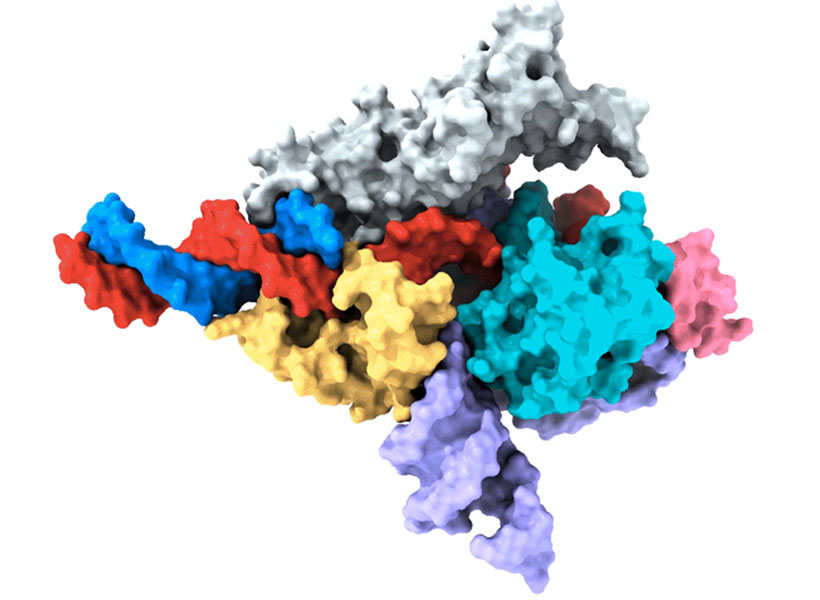

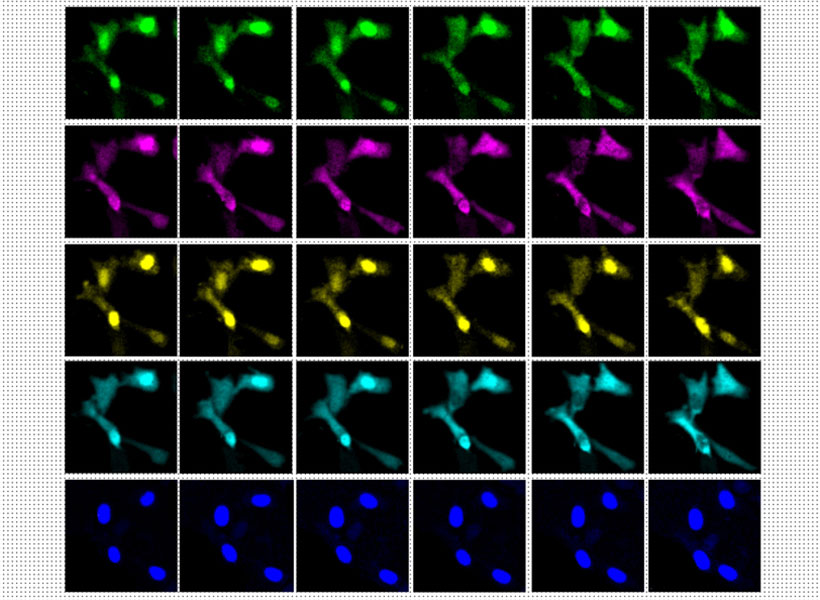

In the new study, the researchers took a different approach: Instead of distinguishing signals based on their physical location, they created fluorescent signals that vary over time. The technique relies on “switchable fluorophores” — fluorescent proteins that turn on and off at a specific rate. For this study, Boyden and his group members identified four green switchable fluorophores, and then engineered two more, all of which turn on and off at different rates. They also identified two red fluorescent proteins that switch at different rates, and engineered one additional red fluorophore.

Image: Courtesy of the researchers

Each of these switchable fluorophores can be used to label a different type of molecule within a living cell, such an enzyme, signaling protein, or part of the cell cytoskeleton. After imaging the cell for several minutes, hours, or even days, the researchers use a computational algorithm to pick out the specific signal from each fluorophore, analogous to how the human ear can pick out different frequencies of sound.

“In a symphony orchestra, you have high-pitched instruments, like the flute, and low-pitched instruments, like a tuba. And in the middle are instruments like the trumpet. They all have different sounds, and our ear sorts them out,” Boyden says.

The mathematical technique that the researchers used to analyze the fluorophore signals is known as linear unmixing. This method can extract different fluorophore signals, similar to how the human ear uses a mathematical model known as a Fourier transform to extract different pitches from a piece of music.

Once this analysis is complete, the researchers can see when and where each of the fluorescently labeled molecules were found in the cell during the entire imaging period. The imaging itself can be done with a simple light microscope, with no specialized equipment required.

Biological phenomena

In this study, the researchers demonstrated their approach by labeling six different molecules involved in the cell division cycle, in mammalian cells. This allowed them to identify patterns in how the levels of enzymes called cyclin-dependent kinases change as a cell progresses through the cell cycle.

The researchers also showed that they could label other types of kinases, which are involved in nearly every aspect of cell signaling, as well as cell structures and organelles such as the cytoskeleton and mitochondria. In addition to their experiments using mammalian cells grown in a lab dish, the researchers showed that this technique could work in the brains of zebrafish larvae.

This method could be useful for observing how cells respond to any kind of input, such as nutrients, immune system factors, hormones, or neurotransmitters, according to the researchers. It could also be used to study how cells respond to changes in gene expression or genetic mutations. All of these factors play important roles in biological phenomena such as growth, aging, cancer, neurodegeneration, and memory formation.

“You could consider all of these phenomena to represent a general class of biological problem, where some short-term event — like eating a nutrient, learning something, or getting an infection — generates a long-term change,” Boyden says.

In addition to pursuing those types of studies, Boyden’s lab is also working on expanding the repertoire of switchable fluorophores so that they can study even more signals within a cell. They also hope to adapt the system so that it could be used in mouse models.

The research was funded by an Alana Fellowship, K. Lisa Yang, John Doerr, Jed McCaleb, James Fickel, Ashar Aziz, the K. Lisa Yang and Hock E. Tan Center for Molecular Therapeutics at MIT, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the National Institutes of Health.