Many of our bodily functions, such as walking, breathing, and chewing, are controlled by brain circuits called central oscillators, which generate rhythmic firing patterns that regulate these behaviors.

MIT neuroscientists have now discovered the neuronal identity and mechanism underlying one of these circuits: an oscillator that controls the rhythmic back-and-forth sweeping of tactile whiskers, or whisking, in mice. This is the first time that any such oscillator has been fully characterized in mammals.

The MIT team found that the whisking oscillator consists of a population of inhibitory neurons in the brainstem that fires rhythmic bursts during whisking. As each neuron fires, it also inhibits some of the other neurons in the network, allowing the overall population to generate a synchronous rhythm that retracts the whiskers from their protracted positions.

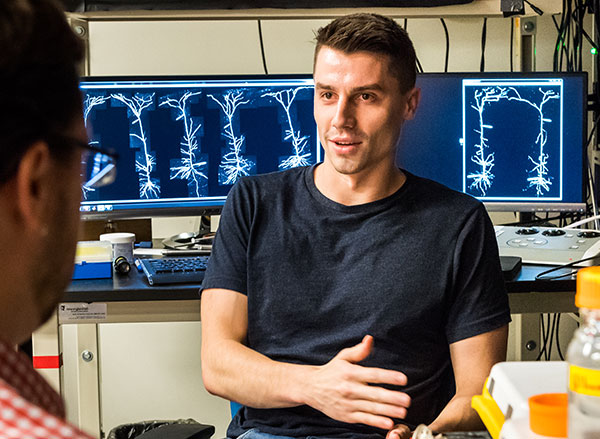

“We have defined a mammalian oscillator molecularly, electrophysiologically, functionally, and mechanistically,” says Fan Wang, an MIT professor of brain and cognitive sciences and a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research. “It’s very exciting to see a clearly defined circuit and mechanism of how rhythm is generated in a mammal.”

Wang is the senior author of the study, which appears today in Nature. The lead authors of the paper are MIT research scientists Jun Takatoh and Vincent Prevosto.

Rhythmic behavior

Most of the research that clearly identified central oscillator circuits has been done in invertebrates. For example, Eve Marder’s lab at Brandeis University found cells in the stomatogastric ganglion in lobsters and crabs that generate oscillatory activity to control rhythmic motion of the digestive tract.

Characterizing oscillators in mammals, especially in awake behaving animals, has proven to be highly challenging. The oscillator that controls walking is believed to be distributed throughout the spinal cord, making it difficult to precisely identify the neurons and circuits involved. The oscillator that generates rhythmic breathing is located in a part of the brain stem called the pre-Bötzinger complex, but the exact identity of the oscillator neurons is not fully understood.

“There haven’t been detailed studies in awake behaving animals, where one can record from molecularly identified oscillator cells and manipulate them in a precise way,” Wang says.

Whisking is a prominent rhythmic exploratory behavior in many mammals, which use their tactile whiskers to detect objects and sense textures. In mice, whiskers extend and retract at a frequency of about 12 cycles per second. Several years ago, Wang’s lab set out try to identify the cells and the mechanism that control this oscillation.

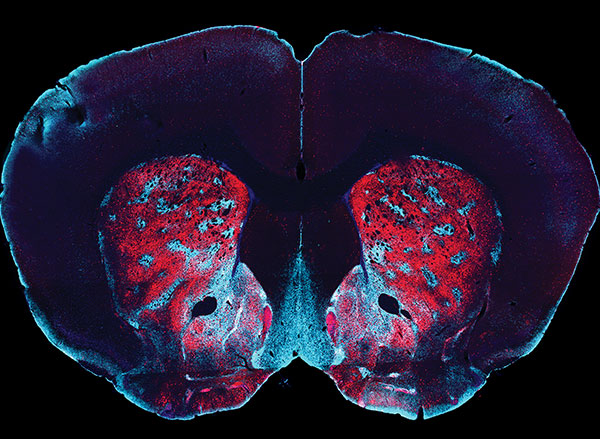

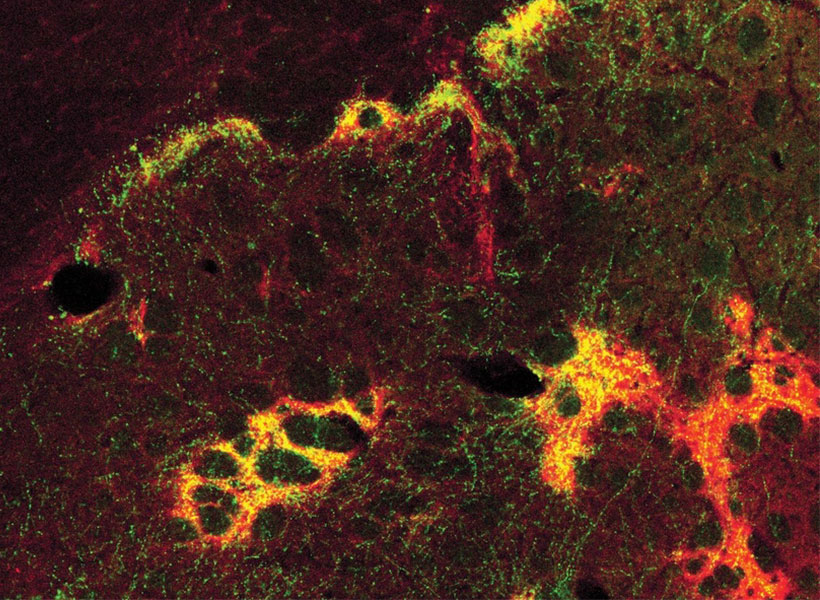

To find the location of the whisking oscillator, the researchers traced back from the motor neurons that innervate whisker muscles. Using a modified rabies virus that infects axons, the researchers were able to label a group of cells presynaptic to these motor neurons in a part of the brainstem called the vibrissa intermediate reticular nucleus (vIRt). This finding was consistent with previous studies showing that damage to this part of the brain eliminates whisking.

The researchers then found that about half of these vIRt neurons express a protein called parvalbumin, and that this subpopulation of cells drives the rhythmic motion of the whiskers. When these neurons are silenced, whisking activity is abolished.

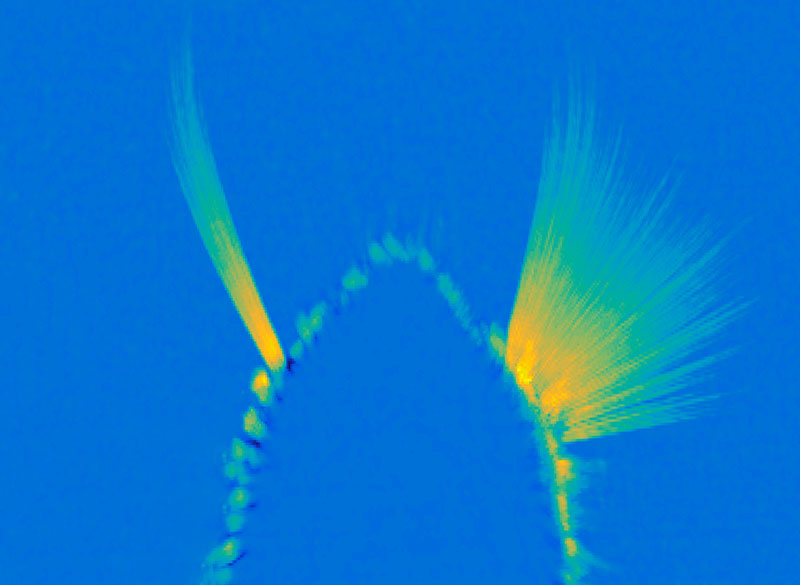

Next, the researchers recorded electrical activity from these parvalbumin-expressing vIRt neurons in brainstem in awake mice, a technically challenging task, and found that these neurons indeed have bursts of activity only during the whisker retraction period. Because these neurons provide inhibitory synaptic inputs to whisker motor neurons, it follows that rhythmic whisking is generated by a constant motor neuron protraction signal interrupted by the rhythmic retraction signal from these oscillator cells.

“That was a super satisfying and rewarding moment, to see that these cells are indeed the oscillator cells, because they fire rhythmically, they fire in the retraction phase, and they’re inhibitory neurons,” Wang says.

“New principles”

The oscillatory bursting pattern of vIRt cells is initiated at the start of whisking. When the whiskers are not moving, these neurons fire continuously. When the researchers blocked vIRt neurons from inhibiting each other, the rhythm disappeared, and instead the oscillator neurons simply increased their rate of continuous firing.

This type of network, known as recurrent inhibitory network, differs from the types of oscillators that have been seen in the stomatogastric neurons in lobsters, in which neurons intrinsically generate their own rhythm.

“Now we have found a mammalian network oscillator that is formed by all inhibitory neurons,” Wang says.

The MIT scientists also collaborated with a team of theorists led by David Golomb at Ben-Gurion University, Israel, and David Kleinfeld at the University of California at San Diego. The theorists created a detailed computational model outlining how whisking is controlled, which fits well with all experimental data. A paper describing that model is appearing in an upcoming issue of Neuron.

Wang’s lab now plans to investigate other types of oscillatory circuits in mice, including those that control chewing and licking.

“We are very excited to find oscillators of these feeding behaviors and compare and contrast to the whisking oscillator, because they are all in the brain stem, and we want to know whether there’s some common theme or if there are many different ways to generate oscillators,” she says.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health.