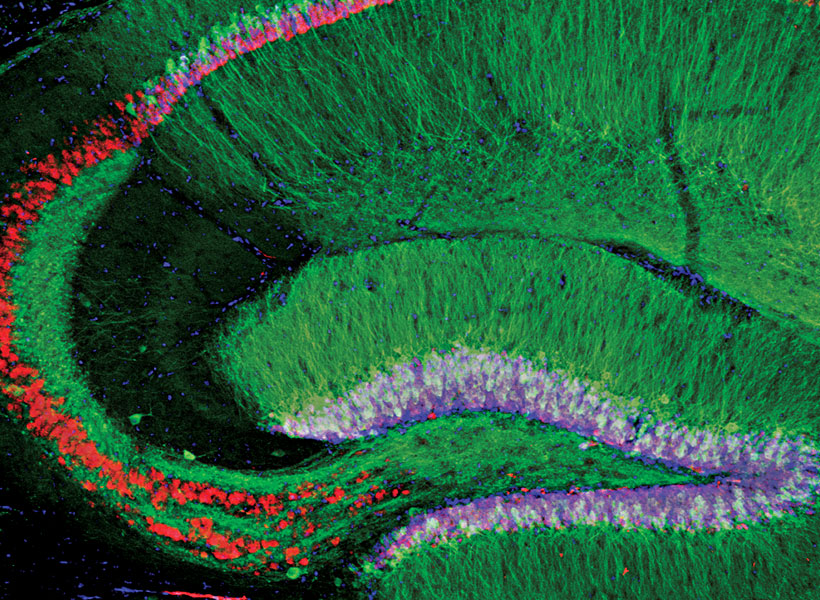

The first comprehensive map of mouse brain activity has been unveiled by a large international collaboration of neuroscientists. Researchers from the International Brain Laboratory (IBL), including McGovern Investigator Ila Fiete, published their findings today in two papers in Nature, revealing insights into how decision-making unfolds across the entire brain in mice at single-cell resolution. This brain-wide activity map challenges the traditional hierarchical view of information processing in the brain and shows that decision-making is distributed across many regions in a highly coordinated way.

“This is the first time anyone has produced a full, brain-wide map of the activity of single neurons during decision-making,” explains Co-Founder of IBL Alexandre Pouget. “The scale is unprecedented as we recorded from over half a million neurons across mice in 12 labs, covering 279 brain areas, which together represent 95% of the mouse brain volume. The decision-making activity, and particularly reward, lit up the brain like a Christmas tree,” adds Pouget, who is also a Group Leader at the University of Geneva.

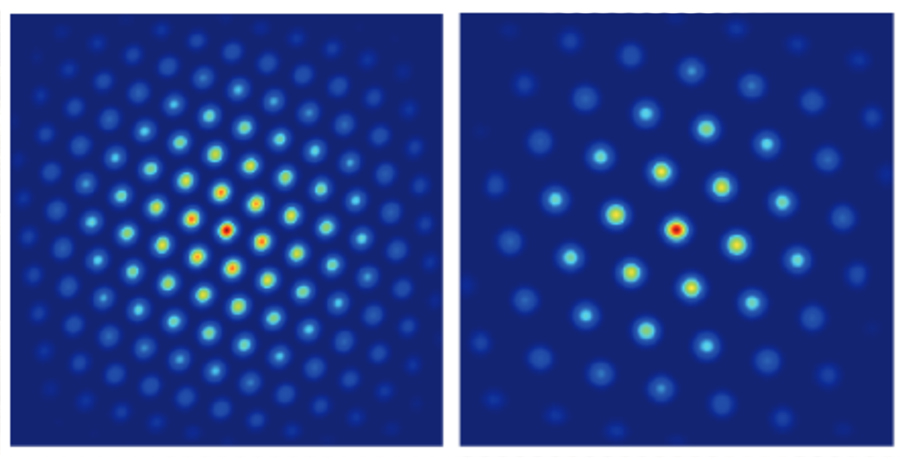

Brain-wide map showing 75,000 analyzed neurons lighting up during different stages of decision-making. At the beginning of the trial, the activity is quiet. Then it builds up in the visual areas at the back of the brain, followed by a rise in activity spreading across the brain as evidence accumulates towards a decision. Next, motor areas light up as there is movement onset and finally there is a spike in activity everywhere in the brain as the animal is rewarded.

Modeling decision-making

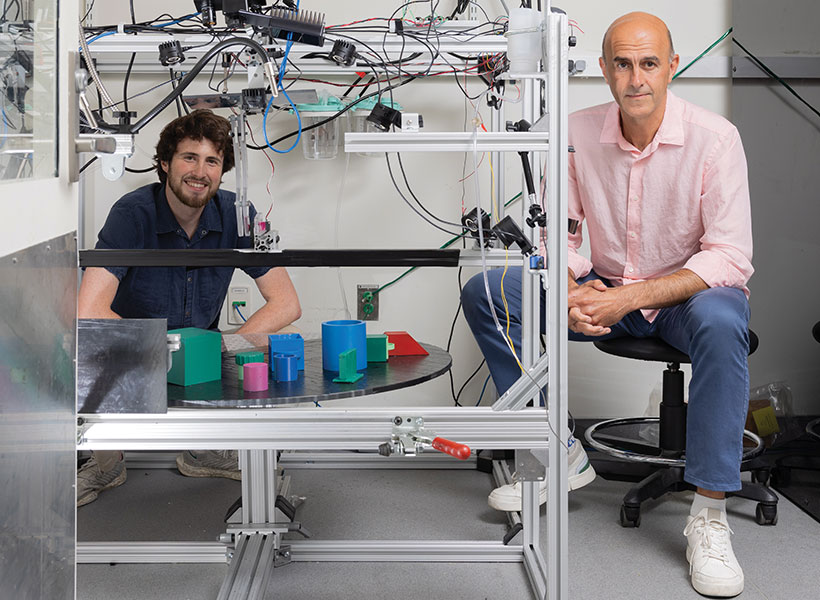

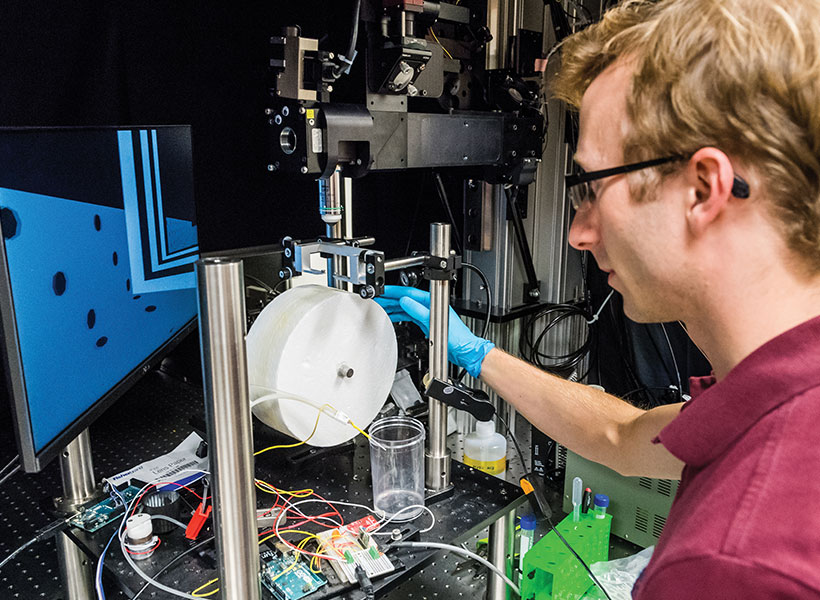

The brain map was made possible by a major international collaboration of neuroscientists from multiple universities, including MIT. Researchers across 12 labs used state-of-the-art silicon electrodes, called Neuropixels probes, for simultaneous neural recordings to measure brain activity while mice were carrying out a decision-making task.

“Participating in the International Brain Laboratory has added new ways for our group to contribute to science,” says Fiete, who is also a professor of brain and cognitive sciences director of the K. Lisa Yang ICoN Center at MIT. “Our lab has helped standardize methods to analyze and generate robust conclusions from data. As computational neuroscientists interested in building models of how the brain works, access to brainwide recordings is incredible: the traditional approach of recording from one or a few brain areas limited our ability to build and test theories, resulting in fragmented models. Now we have the delightful but formidable task to make sense of how all parts of the brain coordinate to perform a behavior. Surprisingly, having a full view of the brain leads to simplifications in the models of decision making.”

The labs collected data from mice performing a decision-making task with sensory, motor, and cognitive components. In the task, a mouse sits in front of a screen and a light appears on the left or right side. If the mouse then responds by moving a small wheel in the correct direction, it receives a reward.

In some trials, the light is so faint that the animal must guess which way to turn the wheel, for which it can use prior knowledge: the light tends to appear more frequently on one side for a number of trials, before the high-frequency side switches. Well-trained mice learn to use this information to help them make correct guesses. These challenging trials therefore allowed the researchers to study how prior expectations influence perception and decision-making.

Brain-wide results

The first paper, “A brain-wide map of neural activity during complex behaviour,” showed that decision-making signals are surprisingly distributed across the brain, not localized to specific regions. This adds brain-wide evidence to a growing number of studies that challenge the traditional hierarchical model of brain function and emphasizes that there is constant communication across brain areas during decision-making, movement onset, and even reward. This means that neuroscientists will need to take a more holistic, brain-wide approach when studying complex behaviors in future.

“The unprecedented breadth of our recordings pulls back the curtain on how the entire brain performs the whole arc of sensory processing, cognitive decision-making, and movement generation,” says Fiete. “Structuring a collaboration that collects a large standardized dataset which single labs could not assemble is a revolutionary new direction for systems neuroscience, initiating the field into the hyper-collaborative mode that has contributed to leaps forward in particle physics and human genetics. Beyond our own conclusions, the dataset and associated technologies, which were released much earlier as part of the IBL mission, have already become a massively used resource for the entire neuroscience community.”

The second paper, “Brain-wide representations of prior information,” showed that prior expectations, our beliefs about what is likely to happen based on our recent experience, are encoded throughout the brain. Surprisingly, these expectations are not only found in cognitive areas, but also brain areas that process sensory information and control actions. For example, expectations are even encoded in early sensory areas such as the thalamus, the brain’s first relay for visual input from the eye. This supports the view that the brain acts as a prediction machine, but with expectations encoded across multiple brain structures playing a central role in guiding behavior responses. These findings could have implications for understanding conditions such as schizophrenia and autism, which are thought to be caused by differences in the way expectations are updated in the brain.

“Much remains to be unpacked: if it is possible to find a signal in a brain area, does it mean that this area is generating the signal, or simply reflecting a signal generated somewhere else? How strongly is our perception of the world is shaped by our expectations? Now we can generate some quantitative answers and begin the next phase experiments to learn about the origins of the expectation signals by intervening to modulate their activity,” says Fiete.

Looking ahead, the team at IBL plan to expand beyond their initial focus on decision-making to explore a broader range of neuroscience questions. With renewed funding in hand, IBL aims to expand its research scope and continue to support large-scale, standardized experiments.

New model of collaborative neuroscience

Officially launched in 2017, IBL introduced a new model of collaboration in neuroscience that uses a standardized set of tools and data processing pipelines shared across multiple labs, enabling the collection of massive datasets while ensuring data alignment and reproducibility. This approach to democratize and accelerate science draws inspiration from large-scale collaborations in physics and biology, such as CERN and the Human Genome Project.

All data from these studies, along with detailed specifications of the tools and protocols used for data collection, are openly accessible to the global scientific community for further analysis and research. Summaries of these resources can be viewed and downloaded on the IBL website under the sections: Data, Tools, Protocols.

This research was supported by grants from Wellcome (209558 and 216324), the Simons Foundation, The National Institutes of Health (NIH U19NS12371601), the National Science Foundation (NSF 1707398), the Gatsby Charitable Foundation (GAT3708), andby the Max Planck Society and the Humboldt Foundation.