What does your license plate say about you?

In the United States, more than 9 million vehicles carry personalized “vanity” license plates, in which preferred words, digits, or phrases replace an otherwise random assignment of letters and numbers to identify a vehicle. While each state and the District of Columbia maintains its own rules about appropriate selections, creativity reigns when choosing a unique vanity plate. What’s more, the stories behind them can be just as fascinating as the people who use them.

It might not come as a surprise to learn that quite a few MIT community members have participated in such vehicular whimsy. Read on to meet some of them and learn about the nerdy, artsy, techy, and MIT-related plates that color their rides.

A little piece of tech heaven

One of the most recognized vehicles around campus is Samuel Klein’s 1998 Honda Civic. More than just the holder of a vanity plate, it’s an art car — a vehicle that’s been custom-designed as a way to express an artistic idea or theme. Klein’s Civic is covered with hundreds of 5.5-inch floppy disks in various colors, and it sports disks, computer keys, and other techy paraphernalia on the interior. With its double-entendre vanity plate, “DSKDRV” (“disk drive”), the art car initially came into being on the West Coast.

Klein, a longtime affiliate of the MIT Media Lab, MIT Press, and MIT Libraries, first heard about the car from fellow Wikimedian and current MIT librarian Phoebe Ayers. An artistic friend of Ayers’, Lara Wiegand, had designed and decorated the car in Seattle but wanted to find a new owner. Klein was intrigued and decided to fly west to check the Civic out.

“I went out there, spent a whole afternoon seeing how she maintained the car and talking about engineering and mechanisms and the logistics of what’s good and bad,” Klein says. “It had already gone through many iterations.”

Klein quickly decided he was up to the task of becoming the new owner. As he drove the car home across the country, it “got a wide range of really cool responses across different parts of the U.S.”

Back in Massachusetts, Klein made a few adjustments: “We painted the hubcaps, we added racing stripes, we added a new generation of laser-etched glass circuits and, you know, I had my own collection of antiquated technology disks that seemed to fit.”

The vanity plate also required a makeover. In Washington state it was “DISKDRV,” but, Klein says, “we had to shave the license plate a bit because there are fewer letters in Massachusetts.”

Today, the car has about 250,000 miles and an Instagram account. “The biggest challenge is just the disks have to be resurfaced, like a lizard, every few years,” says Klein, whose partner, an MIT research scientist, often parks it around campus. “There’s a small collection of love letters for the car. People leave the car notes. It’s very sweet.”

Marking his place in STEM history

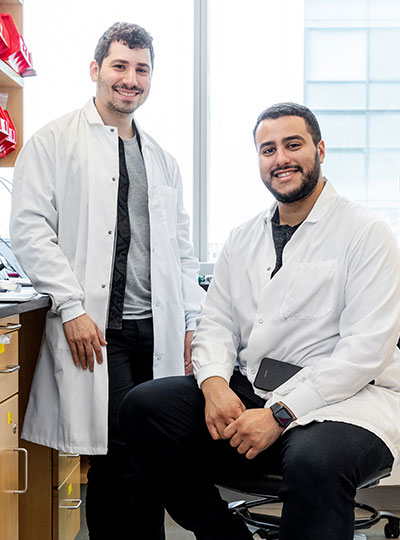

Omar Abudayyeh ’12, PhD ’18, a recent McGovern Fellow at the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT who is now an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, shares an equally riveting story about his vanity plate, “CRISPR,” which adorns his sport utility vehicle.

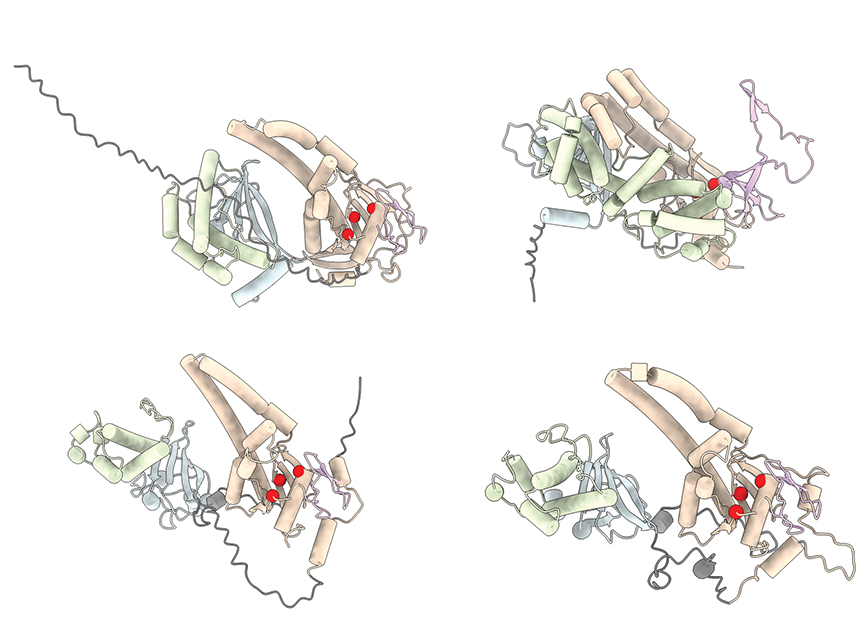

The plate refers to the genome-editing technique that has revolutionized biological and medical research by enabling rapid changes to genetic material. As an MIT graduate student in the lab of Professor Feng Zhang, a pioneering contributor to CRISPR technologies, Abudayyeh was highly involved in early CRISPR development for DNA and RNA editing. In fact, he and Jonathan Gootenberg ’13, another recent McGovern Fellow and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School who works closely with Abudayyeh, discovered many novel CRISPR enzymes, such as Cas12 and Cas13, and applied these technologies for both gene therapy and CRISPR diagnostics.

So how did Abudayyeh score his vanity plate? It was all due to his attendance at a genome-editing conference in 2022, where another early-stage CRISPR researcher, Samuel Sternberg, showed up in a car with New York “CRISPR” plates. “It became quite a source of discussion at the conference, and at one of the breaks, Sam and his labmates egged us on to get the Massachusetts license plate,” Abudayyeh explains. “I insisted that it must be taken, but I applied anyway, paying the 70 dollars and then receiving a message that I would get a letter eight to 12 weeks later about whether the plate was available or not. I then returned to Boston and forgot about it until a couple months later when, to my surprise, the plate arrived in the mail.”

While Abudayyeh continues his affiliation with the McGovern Institute, he and Gootenberg recently set up a lab at Harvard Medical School as new faculty members. “We have continued to discover new enzymes, such as Cas7-11, that enable new frontiers, such as programmable proteases for RNA sensing and novel therapeutics, and we’ve applied CRISPR technologies for new efforts in gene editing and aging research,” Abudayyeh notes.

As for his license plate, he says, “I’ve seen instances of people posting about it on Twitter or asking about it in Slack channels. A number of times, people have stopped me to say they read the Walter Isaacson book on CRISPR, asking how I was related to it. I would then explain my story — and describe how I’m actually in the book, in the chapters on CRISPR diagnostics.”

Displaying MIT roots, nerd pride

For some, a connection to MIT is all the reason they need to register a vanity plate — or three. Jeffrey Chambers SM ’06, PhD ’14, a graduate of the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, shares that he drives with a Virginia license plate touting his “PHD MIT.” Professor of biology Anthony Sinskey ScD ’67 owns several vehicles sporting vanity plates that honor Course 20, which is today the Department of Biological Engineering but has previously been known by Food Technology, Nutrition and Food Science, and Applied Biological Sciences. Sinskey says he has both “MIT 20” and “MIT XX” plates in Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

At least two MIT couples have had dual vanity plates. Says Laura Kiessling ’83, professor of chemistry: “My plate is ‘SLEX.’ This is the abbreviation for a carbohydrate called sialyl Lewis X. It has many roles, including a role in fertilization (sperm-egg binding). It tends to elicit many different reactions from people asking me what it means. Unless they are scientists, I say that my husband [Ron Raines ’80, professor of biology] gave it to me as an inside joke. My husband’s license plate is ‘PROTEIN.’”

Professor of the practice emerita Marcia Bartusiak of MIT Comparative Media Studies/Writing and her husband, Stephen Lowe PhD ’88, previously shared a pair of related license plates. When the couple lived in Virginia, Lowe working as a mathematician on the structure of spiral galaxies and Bartusiak a young science writer focused on astronomy, they had “SPIRAL” and “GALAXY” plates. Now retired in Massachusetts, while they no longer have registered vanity plates, they’ve named their current vehicles “Redshift” and “Blueshift.”

Still other community members have plates that make a nod to their hobbies — such as Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences and AeroAstro Professor Sara Seager’s “ICANOE” — or else playfully connect with fellow drivers. Julianna Mullen, communications director in the Plasma Science and Fusion Center, says of her “OMGWHY” plate: “It’s just an existential reminder of the importance of scientific inquiry, especially in traffic when someone cuts you off so they can get exactly two car lengths ahead. Oh my God, why did they do it?”

Are you an MIT affiliate with a unique vanity plate? We’d love to see it!