Unpacking auditory hallucinations

Neuroimaging studies are beginning to reveal a clearer picture of the brain systems involved in schizophrenia.

Tamar Regev, the 2022–2024 Poitras Center Postdoctoral Fellow, has identified a new neural system that may shed light on the auditory hallucinations experienced by patients diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Fellow in Ev Fedorenko’s lab at the McGovern Institute. Photo: Steph Stevens

“The system appears integral to prosody processing,”says Regev. “‘Prosody’ can be described as the melody of speech — auditory gestures that we use when we’re speaking to signal linguistic, emotional, and social information.” The prosody processing system Regev has uncovered is distinct from the lower-level auditory speech processing system as well as the higher-level language processing system. Regev aims to understand how the prosody system, along with the speech and language processing systems, may be impaired in neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, especially when experienced with auditory hallucinations in the form of speech.

“Knowing which neural systems are affected by schizophrenia can lay the groundwork for future research into interventions that target the mechanisms underlying symptoms such as hallucinations,” says Regev. Passionate about bridging gaps between disciplines, she is collaborating with Ann Shinn, MD, MPH, of McLean Hospital’s Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder Research Program.

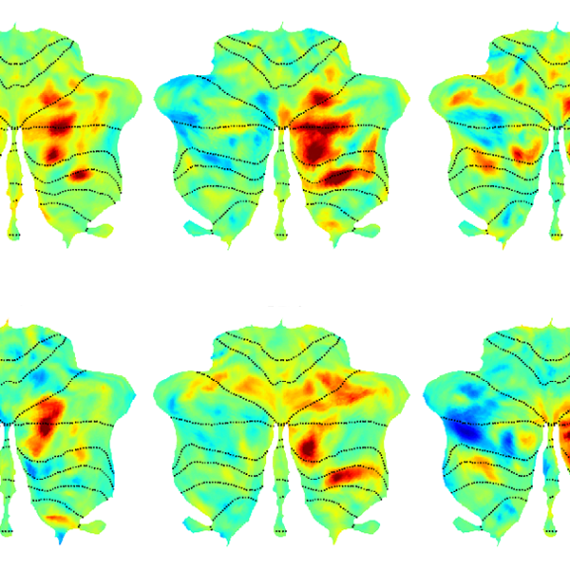

Regev’s graduate work at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem focused on exploring the auditory system with electroencephalography (EEG), which measures electrical activity in the brain using small electrodes attached to the scalp. She came to MIT to study under Evelina Fedorenko, a world leader in researching the cognitive and neural mechanisms underlying language processing. With Fedorenko she has learned to use functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which reveals the brain’s functional anatomy by measuring small changes in blood flow that occur with brain activity.

“I hope my research will lead to a better understanding of the neural architectures that underlie these disorders—and eventually help us as a society to better understand and accept special populations.”- Tamar Regev

“EEG has very good temporal resolution but poor spatial resolution, while fMRI provides a map of the brain showing where neural signals are coming from,” says Regev. “With fMRI I can connect my work on the auditory system with that on the language system.”

Regev developed a unique fMRI paradigm to do that. While her human subjects are in the scanner, she is comparing brain responses to speech with expressive prosody versus flat prosody to find the role of the prosody system among the auditory, speech, and language regions. She plans to apply her findings to analyze a rich data set drawn from fMRI studies that Fedorenko and Shinn began a few years ago while investigating the neural basis of auditory hallucinations in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Regev is exploring how the neural architecture may differ between control subjects and those with and without auditory hallucinations as well as those with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

“This is the first time these questions are being asked using the individual-subject approach developed in the Fedorenko lab,” says Regev. The approach provides superior sensitivity, functional resolution, interpretability, and versatility compared with the group analyses of the past. “I hope my research will lead to a better understanding of the neural architectures that underlie these disorders,” says Regev, “and eventually help us as a society to better understand and accept special populations.”