With every step we take, our brains are already thinking about the next one. If a bump in the terrain or a minor misstep has thrown us off balance, our stride may need to be altered to prevent a fall. Our two-legged posture makes maintaining stability particularly complex, which our brains solve in part by continually monitoring our bodies and adjusting where we place our feet.

Now, scientists at MIT’s McGovern Institute have determined that animals with very different bodies likely use a shared strategy to balance themselves when they walk.

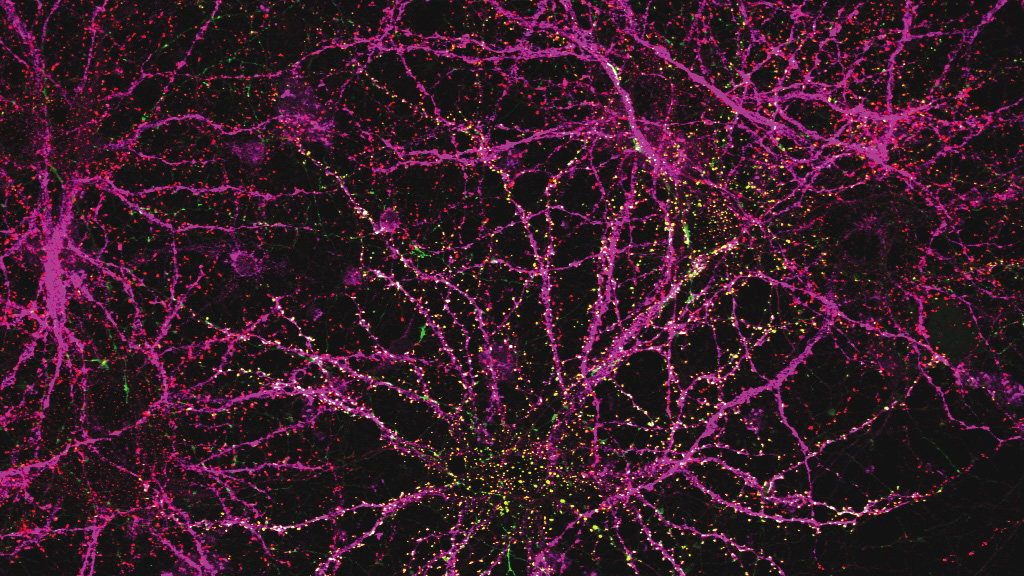

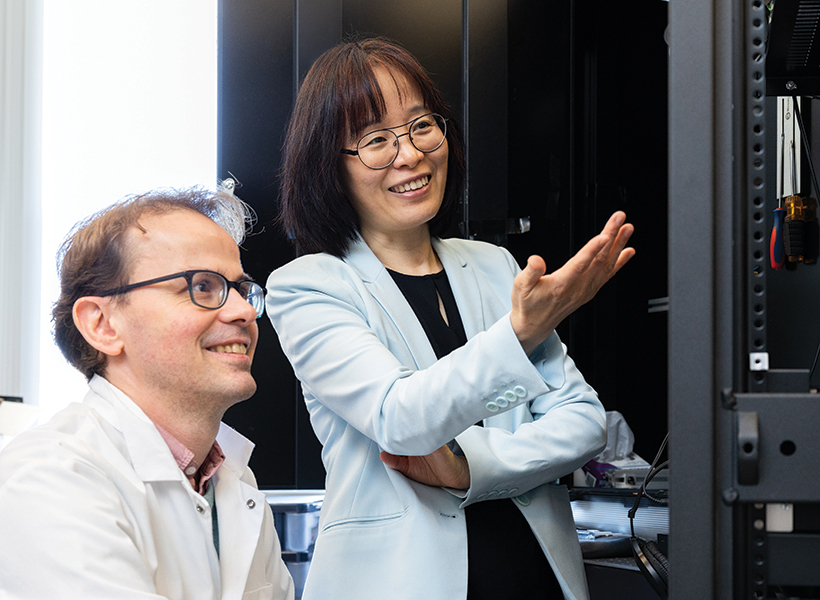

McGovern Associate Investigator Nidhi Seethapathi and K. Lisa Yang ICoN Center Fellow Antoine De Comite found that humans, mice, and fruit flies all use an error-correction process to guide foot placement and maintain stability while walking. Their findings, published October 21, 2025, in the journal PNAS, could inform future studies exploring how the brain achieves stability during locomotion – bridging the gap between animal models and human balance.

Corrective action

Information must be integrated by the brain to keep us upright when we walk or run. Our steps must be continually adjusted according to the terrain, our desired speed, and our body’s current velocity and position in space.

“We rely on a combination of vestibular, proprioceptive, and visual information to build an estimate of our body’s state, determining if we are about to fall. Once we know the body’s state, we can decide which corrective actions to take,” explains Seethapathi, who is also the Frederick A. (1971) and Carole J. Middleton Career Development Assistant Professor in Brain and Cognitive Sciences and Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT.

While humans are known to adjust where they place their feet to correct for errors, it is not known whether animals whose bodies are more stable do this, too.

To find out, Seethapathi and De Comite, who is a postdoctoral research in both Seethapathi’s and Guoping Feng’s labs, turned to locomotion data from mice, fruit flies, and humans shared by other labs, enabling an analysis across species which is otherwise challenging. Importantly, Seethapathi notes, all the animals they studied were walking in everyday natural environments, such as around a room—not on a treadmill or over unusual terrain.

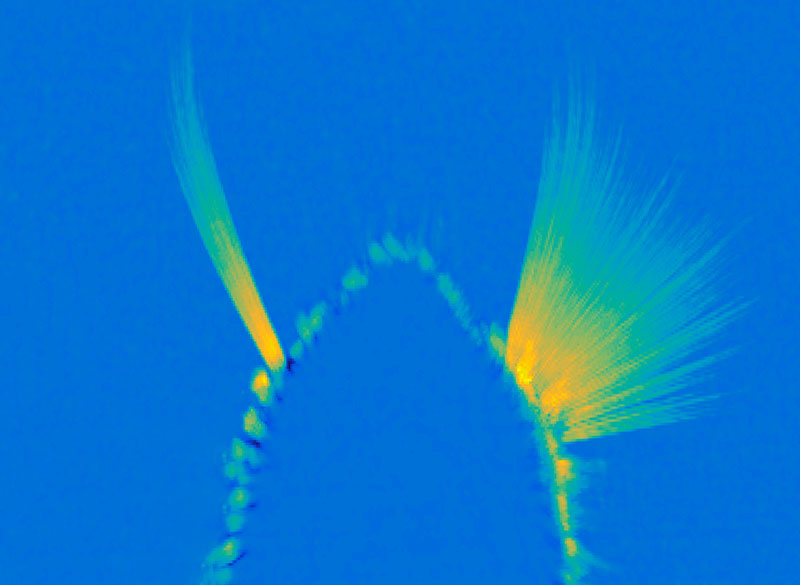

Even in these ordinary circumstances, missteps and minor imbalances are common, and the team’s analysis showed that these errors predicted where all of the animals placed their feet in subsequent steps, regardless of whether they had two, four, or six legs.

By tracking the animals’ bodies and the step-by-step placement of their feet, Seethapathi and De Comite were able to find a measure of error that informs each animal’s next step. “By taking this comparative approach, we’ve forced ourselves to come up with a definition of error that generalizes across species,” Seethapathi says. “An animal moves with an expected body state for a particular speed. If it deviates from that ideal state, that deviation—at any given moment—is the error.”

“It was surprising to find similarities across these three species, which, at first sight, look very different,” says DeComite.

“The methods themselves are surprising because we now have a pipeline to analyze foot placement and locomotion stability in any legged species,” explains DeComite, “which could lead similar analyses in even more species in the future.”

The team’s data suggest that in all of the species in the study, placement of the feet is guided both by an error-correction process and the speed at which an animal is traveling. Steps tend to lengthen and feet spend less time on the ground as animals pick up their pace, while the width of each step seems to change largely to compensate for body-state errors.

Now, Seethapathi says, we can look forward to future studies to explore how the dual control systems might be generated and integrated in the brain to keep moving bodies stable.

Studying how brains help animals move stably may also guide the development of more targeted strategies to help people improve their balance and, ultimately, prevent falls.

“In elderly individuals and individuals with sensorimotor disorders , minimizing fall risk is one of the major functional targets of rehabilitation,” says Seethapathi. “A fundamental understanding of the error correction process that helps us remain stable will provide insight into why this process falls short in populations with neural deficits,” she says.