Digital technologies, such as smartphones and machine learning, have revolutionized education. At the McGovern Institute for Brain Research’s 2024 Spring Symposium, “Transformational Strategies in Mental Health,” experts from across the sciences — including psychiatry, psychology, neuroscience, computer science, and others — agreed that these technologies could also play a significant role in advancing the diagnosis and treatment of mental health disorders and neurological conditions.

Co-hosted by the McGovern Institute, MIT Open Learning, McClean Hospital, the Poitras Center for Psychiatric Disorders Research at MIT, and the Wellcome Trust, the symposium raised the alarm about the rise in mental health challenges and showcased the potential for novel diagnostic and treatment methods.

“We have to do something together as a community of scientists and partners of all kinds to make a difference.” – John Gabrieli

John Gabrieli, the Grover Hermann Professor of Health Sciences and Technology at MIT, kicked off the symposium with a call for an effort on par with the Manhattan Project, which in the 1940s saw leading scientists collaborate to do what seemed impossible. While the challenge of mental health is quite different, Gabrieli stressed, the complexity and urgency of the issue are similar. In his later talk, “How can science serve psychiatry to enhance mental health?,” he noted a 35 percent rise in teen suicide deaths between 1999 and 2000 and, between 2007 and 2015, a 100 percent increase in emergency room visits for youths ages 5 to 18 who experienced a suicide attempt or suicidal ideation.

“We have no moral ambiguity, but all of us speaking today are having this meeting in part because we feel this urgency,” said Gabrieli, who is also a professor of brain and cognitive sciences, the director of the Integrated Learning Initiative (MITili) at MIT Open Learning, and a member of the McGovern Institute. “We have to do something together as a community of scientists and partners of all kinds to make a difference.”

An urgent problem

In 2021, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory on the increase in mental health challenges in youth; in 2023, he issued another, warning of the effects of social media on youth mental health. At the symposium, Susan Whitfield-Gabrieli, a research affiliate at the McGovern Institute and a professor of psychology and director of the Biomedical Imaging Center at Northeastern University, cited these recent advisories, saying they underscore the need to “innovate new methods of intervention.”

Other symposium speakers also highlighted evidence of growing mental health challenges for youth and adolescents. Christian Webb, associate professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School, stated that by the end of adolescence, 15-20 percent of teens will have experienced at least one episode of clinical depression, with girls facing the highest risk. Most teens who experience depression receive no treatment, he added.

Adults who experience mental health challenges need new interventions, too. John Krystal, the Robert L. McNeil Jr. Professor of Translational Research and chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine, pointed to the limited efficacy of antidepressants, which typically take about two months to have an effect on the patient. Patients with treatment-resistant depression face a 75 percent likelihood of relapse within a year of starting antidepressants. Treatments for other mental health disorders, including bipolar and psychotic disorders, have serious side effects that can deter patients from adherence, said Virginie-Anne Chouinard, director of research at McLean OnTrackTM, a program for first episode psychosis at McLean Hospital.

New treatments, new technologies

Emerging technologies, including smartphone technology and artificial intelligence, are key to the interventions that symposium speakers shared.

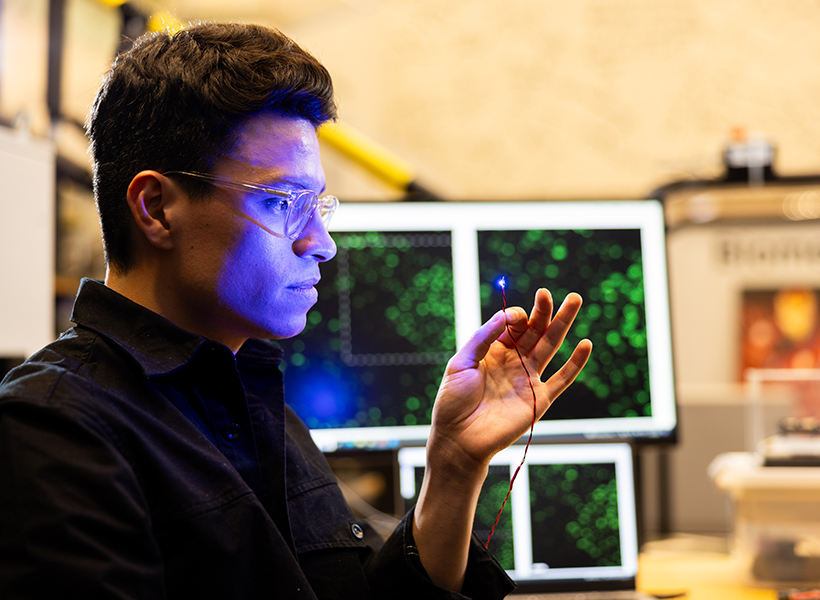

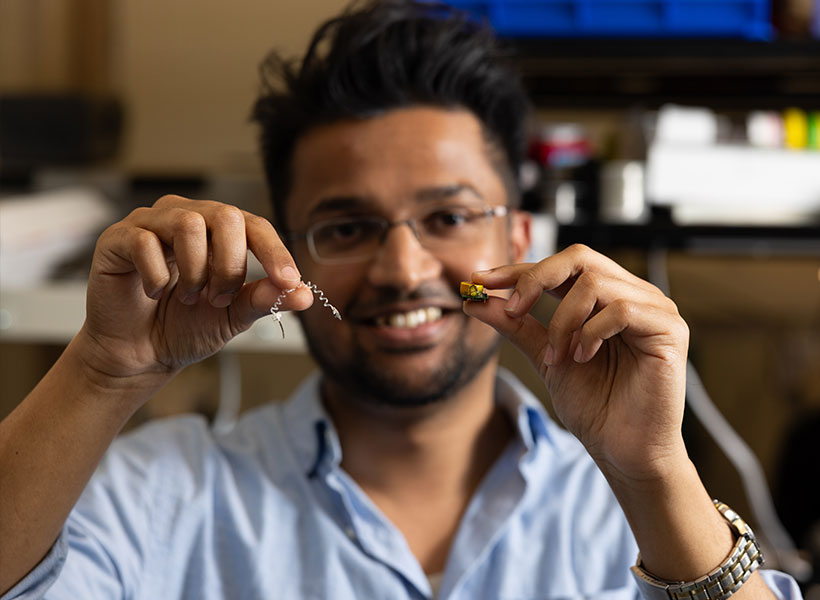

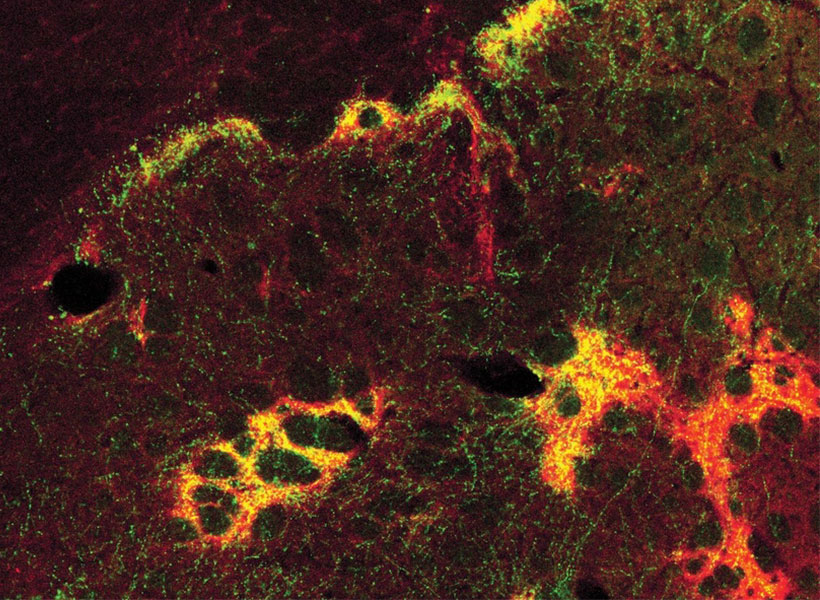

In a talk on AI and the brain, Dina Katabi, the Thuan and Nicole Pham Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT, discussed novel ways to detect Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, among other diseases. Early-stage research involved developing devices that can analyze how movement within a space impacts the surrounding electromagnetic field, as well as how wireless signals can detect breathing and sleep stages.

“I realize this may sound like la-la land,” Katabi said. “But it’s not! This device is used today by real patients, enabled by a revolution in neural networks and AI.”

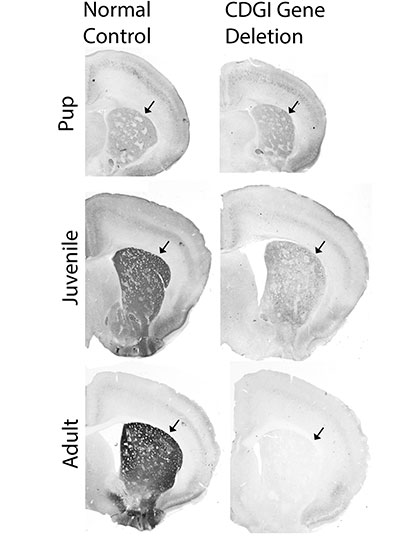

Parkinson’s disease often cannot be diagnosed until significant impairment has already occurred. In a set of studies, Katabi’s team collected data on nocturnal breathing and trained a custom neural network to detect occurrences of Parkinson’s. They found the network was over 90 percent accurate in its detection. Next, the team used AI to analyze two sets of breathing data collected from patients at a six-year interval. Could their custom neural network identify patients who did not have a Parkinson’s diagnosis on the first visit, but subsequently received one? The answer was largely yes: Machine learning identified 75 percent of patients who would go on to receive a diagnosis.

Detecting high-risk patients at an early stage could make a substantial difference for intervention and treatment. Similarly, research by Jordan Smoller, professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and director of the Center for Precision Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, demonstrated that AI-aided suicide risk prediction model could detect 45 percent of suicide attempts or deaths with 90 percent specificity, about two to three years in advance.

Other presentations, including a series of lightning talks, shared new and emerging treatments, such as the use of ketamine to treat depression; the use of smartphones, including daily text surveys and mindfulness apps, in treating depression in adolescents; metabolic interventions for psychotic disorders; the use of machine learning to detect impairment from THC intoxication; and family-focused treatment, rather than individual therapy, for youth depression.

Advancing understanding

The frequency and severity of adverse mental health events for children, adolescents, and adults demonstrate the necessity of funding for mental health research — and the open sharing of these findings.

Niall Boyce, head of mental health field building at the Wellcome Trust — a global charitable foundation dedicated to using science to solve urgent health challenges — outlined the foundation’s funding philosophy of supporting research that is “collaborative, coherent, and focused” and centers on “What is most important to those most affected?” Wellcome research managers Anum Farid and Tayla McCloud stressed the importance of projects that involve people with lived experience of mental health challenges and “blue sky thinking” that takes risks and can advance understanding in innovative ways. Wellcome requires that all published research resulting from its funding be open and accessible in order to maximize their benefits.

Whether through therapeutic models, pharmaceutical treatments, or machine learning, symposium speakers agreed that transformative approaches to mental health call for collaboration and innovation.

“Understanding mental health requires us to understand the unbelievable diversity of humans,” Gabrieli said. “We have to use all the tools we have now to develop new treatments that will work for people for whom our conventional treatments don’t.”