Most pharmaceuticals must either be ingested or injected into the body to do their work. Either way, it takes some time for them to reach their intended targets, and they also tend to spread out to other areas of the body. Now, researchers at the McGovern Institute at MIT and elsewhere have developed a system to deliver medical treatments that can be released at precise times, minimally-invasively, and that ultimately could also deliver those drugs to specifically targeted areas such as a specific group of neurons in the brain.

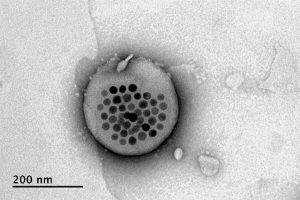

The new approach is based on the use of tiny magnetic particles enclosed within a tiny hollow bubble of lipids (fatty molecules) filled with water, known as a liposome. The drug of choice is encapsulated within these bubbles, and can be released by applying a magnetic field to heat up the particles, allowing the drug to escape from the liposome and into the surrounding tissue.

The findings are reported today in the journal Nature Nanotechnology in a paper by MIT postdoc Siyuan Rao, Associate Professor Polina Anikeeva, and 14 others at MIT, Stanford University, Harvard University, and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich.

“We wanted a system that could deliver a drug with temporal precision, and could eventually target a particular location,” Anikeeva explains. “And if we don’t want it to be invasive, we need to find a non-invasive way to trigger the release.”

Magnetic fields, which can easily penetrate through the body — as demonstrated by detailed internal images produced by magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI — were a natural choice. The hard part was finding materials that could be triggered to heat up by using a very weak magnetic field (about one-hundredth the strength of that used for MRI), in order to prevent damage to the drug or surrounding tissues, Rao says.

Rao came up with the idea of taking magnetic nanoparticles, which had already been shown to be capable of being heated by placing them in a magnetic field, and packing them into these spheres called liposomes. These are like little bubbles of lipids, which naturally form a spherical double layer surrounding a water droplet.

Image courtesy of the researchers

When placed inside a high-frequency but low-strength magnetic field, the nanoparticles heat up, warming the lipids and making them undergo a transition from solid to liquid, which makes the layer more porous — just enough to let some of the drug molecules escape into the surrounding areas. When the magnetic field is switched off, the lipids re-solidify, preventing further releases. Over time, this process can be repeated, thus releasing doses of the enclosed drug at precisely controlled intervals.

The drug carriers were engineered to be stable inside the body at the normal body temperature of 37 degrees Celsius, but able to release their payload of drugs at a temperature of 42 degrees. “So we have a magnetic switch for drug delivery,” and that amount of heat is small enough “so that you don’t cause thermal damage to tissues,” says Anikeeva, who also holds appointments in the departments of Materials Science and Engineering and the Brain and Cognitive Sciences.

In principle, this technique could also be used to guide the particles to specific, pinpoint locations in the body, using gradients of magnetic fields to push them along, but that aspect of the work is an ongoing project. For now, the researchers have been injecting the particles directly into the target locations, and using the magnetic fields to control the timing of drug releases. “The technology will allow us to address the spatial aspect,” Anikeeva says, but that has not yet been demonstrated.

This could enable very precise treatments for a wide variety of conditions, she says. “Many brain disorders are characterized by erroneous activity of certain cells. When neurons are too active or not active enough, that manifests as a disorder, such as Parkinson’s, or depression, or epilepsy.” If a medical team wanted to deliver a drug to a specific patch of neurons and at a particular time, such as when an onset of symptoms is detected, without subjecting the rest of the brain to that drug, this system “could give us a very precise way to treat those conditions,” she says.

Rao says that making these nanoparticle-activated liposomes is actually quite a simple process. “We can prepare the liposomes with the particles within minutes in the lab,” she says, and the process should be “very easy to scale up” for manufacturing. And the system is broadly applicable for drug delivery: “we can encapsulate any water-soluble drug,” and with some adaptations, other drugs as well, she says.

One key to developing this system was perfecting and calibrating a way of making liposomes of a highly uniform size and composition. This involves mixing a water base with the fatty acid lipid molecules and magnetic nanoparticles and homogenizing them under precisely controlled conditions. Anikeeva compares it to shaking a bottle of salad dressing to get the oil and vinegar mixed, but controlling the timing, direction and strength of the shaking to ensure a precise mixing.

Anikeeva says that while her team has focused on neurological disorders, as that is their specialty, the drug delivery system is actually quite general and could be applied to almost any part of the body, for example to deliver cancer drugs, or even to deliver painkillers directly to an affected area instead of delivering them systemically and affecting the whole body. “This could deliver it to where it’s needed, and not deliver it continuously,” but only as needed.

Because the magnetic particles themselves are similar to those already in widespread use as contrast agents for MRI scans, the regulatory approval process for their use may be simplified, as their biological compatibility has largely been proven.

The team included researchers in MIT’s departments of Materials Science and Engineering and Brain and Cognitive Sciences, as well as the McGovern Institute for Brain Research, the Simons Center for Social Brain, and the Research Laboratory of Electronics; the Harvard University Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology and the John A. Paulsen School of Engineering and Applied Sciences; Stanford University; and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. The work was supported by the Simons Postdoctoral Fellowship, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the Bose Research Grant, and the National Institutes of Health.