As people age, their immune system function declines. T cell populations become smaller and can’t react to pathogens as quickly, making people more susceptible to a variety of infections.

To try to overcome that decline, researchers at MIT and the Broad Institute have found a way to temporarily program cells in the liver to improve T-cell function. This reprogramming can compensate for the age-related decline of the thymus, where T cell maturation normally occurs.

Using mRNA to deliver three key factors that usually promote T-cell survival, the researchers were able to rejuvenate the immune systems of mice. Aged mice that received the treatment showed much larger and more diverse T cell populations in response to vaccination, and they also responded better to cancer immunotherapy treatments. Their findings are published in the December 17 issue of the journal Nature.

If developed for use in patients, this type of treatment could help people lead healthier lives as they age, the researchers say.

“If we can restore something essential like the immune system, hopefully we can help people stay free of disease for a longer span of their life,” says Feng Zhang, the James and Patricia Poitras Professor of Neuroscience at MIT, who has joint appointments in the departments of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and Biological Engineering.

Zhang, who is also an investigator at the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT, a core institute member at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, an investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and co-director of the K. Lisa Yang and Hock E. Tan Center for Molecular Therapeutics at MIT, is the senior author of the new study. Former MIT postdoc Mirco Friedrich is the lead author of the paper, which appears today in Nature.

A temporary factory

The thymus, a small organ located in front of the heart, plays a critical role in T-cell development. Within the thymus, immature T cells go through a checkpoint process that ensures a diverse repertoire of T cells. The thymus also secretes cytokines and growth factors that help T cells to survive.

However, starting in early adulthood, the thymus begins to shrink. This process, known as thymic involution, leads to a decline in the production of new T cells. By the age of approximately 75, the thymus is greatly reduced.

“As we get older, the immune system begins to decline. We wanted to think about how can we maintain this kind of immune protection for a longer period of time, and that’s what led us to think about what we can do to boost immunity,” Friedrich says.

Previous work on rejuvenating the immune system has focused on delivering T cell growth factors into the bloodstream, but that can have harmful side effects. Researchers are also exploring the possibility of using transplanted stem cells to help regrow functional tissue in the thymus.

The MIT team took a different approach: They wanted to see if they could create a temporary “factory” in the body that would generate the T-cell-stimulating signals that are normally produced by the thymus.

“Our approach is more of a synthetic approach,” Zhang says. “We’re engineering the body to mimic thymic factor secretion.”

For their factory location, they settled on the liver, for several reasons. First, the liver has a high capacity for producing proteins, even in old age. Also, it’s easier to deliver mRNA to the liver than to most other organs of the body. The liver was also an appealing target because all of the body’s circulating blood has to flow through it, including T cells.

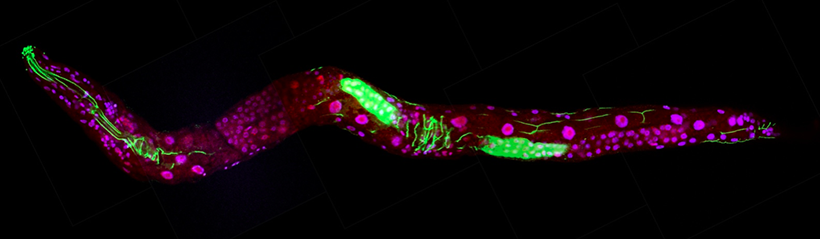

To create their factory, the researchers identified three immune cues that are important for T-cell maturation. They encoded these three factors into mRNA sequences that could be delivered by lipid nanoparticles. When injected into the bloodstream, these particles accumulate in the liver and the mRNA is taken up by hepatocytes, which begin to manufacture the proteins encoded by the mRNA.

The factors that the researchers delivered are DLL1, FLT-3, and IL-7, which help immature progenitor T cells mature into fully differentiated T cells.

Immune rejuvenation

Tests in mice revealed a variety of beneficial effects. First, the researchers injected the mRNA particles into 18-month-old mice, equivalent to humans in their 50s. Because mRNA is short-lived, the researchers gave the mice multiple injections over four weeks to maintain a steady production by the liver.

After this treatment, T cell populations showed significant increases in size and function.

The researchers then tested whether the treatment could enhance the animals’ response to vaccination. They vaccinated the mice with ovalbumin, a protein found in egg whites that is commonly used to study how the immune system responds to a specific antigen. In 18-month-old mice that received the mRNA treatment before vaccination, the researchers found that the population of cytotoxic T-cells specific to ovalbumin doubled, compared to mice of the same age that did not receive the mRNA treatment.

The mRNA treatment can also boost the immune system’s response to cancer immunotherapy, the researchers found. They delivered the mRNA treatment to 18-month-old mice, who were then implanted with tumors and treated with a checkpoint inhibitor drug. This drug, which targets the protein PD-L1, is designed to help take the brakes off the immune system and stimulate T cells to attack tumor cells.

Mice that received the treatment showed much higher survival rates and longer lifespan that those that received the checkpoint inhibitor drug but not the mRNA treatment.

The researchers found that all three factors were necessary to induce this immune enhancement; none could achieve all aspects of it on their own. They now plan to study the treatment in other animal models and to identify additional signaling factors that may further enhance immune system function. They also hope to study how the treatment affects other immune cells, including B cells.

Other authors of the paper include Julie Pham, Jiakun Tian, Hongyu Chen, Jiahao Huang, Niklas Kehl, Sophia Liu, Blake Lash, Fei Chen, Xiao Wang, and Rhiannon Macrae.

The research was funded, in part, by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the K. Lisa Yang Brain-Body Center, part of the Yang Tan Collective at MIT, Broad Institute Programmable Therapeutics Gift Donors, the Pershing Square Foundation, J. and P. Poitras, and an EMBO Postdoctoral Fellowship.