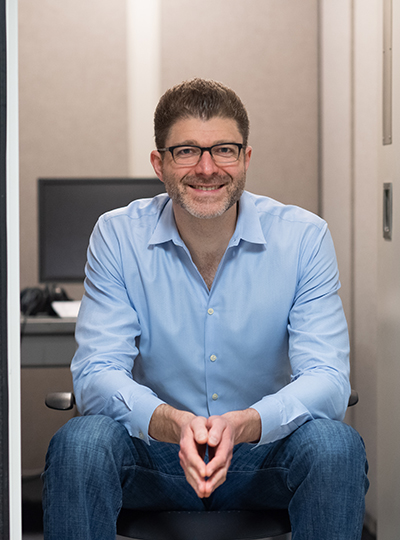

Today the McGovern Institute at MIT announces that the 2025 Edward M. Scolnick Prize in Neuroscience will be awarded to Leslie Vosshall, the Robin Chemers Neustein Professor at The Rockefeller University and Vice President and Chief Scientific Officer of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Vosshall is being recognized for her discovery of the neural mechanisms underlying mosquito host-seeking behavior. The Scolnick Prize is awarded annually by the McGovern Institute for outstanding achievements in neuroscience.

“Leslie Vosshall’s vision to apply decades of scientific know-how in a model insect to bear on one of the greatest human health threats, the mosquito, is awe-inspiring,” says McGovern Institute Director and chair of the selection committee, Robert Desimone. “Vosshall brought together academic and industry scientists to create the first fully annotated genome of the deadly Aedes aegypti mosquito and she became the first to apply powerful CRISPR-Cas9 editing to study this species.”

Vosshall was born in Switzerland, moved to the US as a child and worked throughout high school and college in her uncle’s laboratory, alongside Gerald Weissman, at the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole. During this time, she published a number of papers on cell aggregation and neutrophil signaling and received a BA in 1987 from Columbia University. She went to graduate school at The Rockefeller University where she first began working on the genetic model organism, the fruit fly Drosophila. Her mentor was Michael Young, who had just recently cloned the circadian rhythm gene period, work for which he later shared the Nobel Prize. Vosshall contributed to this work by showing that the gene timeless is required for rhythmic cycling of the PERIOD protein in and out of a cell’s nucleus and that this is required in only a subset of brain cells to drive circadian behaviors.

For her postdoctoral research, Vosshall returned to Columbia University in 1993 to join the laboratory of Richard Axel, also a future Nobel Laureate. There, Vosshall began her studies of olfaction and was one of the first to clone olfactory receptors in fruit flies. She mapped the expression pattern of each of the fly’s 60 or so olfactory receptors to individual sensory neurons and showed that each sensory neuron has a stereotyped projection into the brain. This work revealed that there is a topological map of brain activity responses for different odorants.

Vosshall started her own laboratory to study the mechanisms of olfaction and olfactory behavior in 2000, at The Rockefeller University. She rose through the ranks to receive tenure in 2006 and full professorship in 2010. Vosshall’s group was initially focused on the classic fruit fly model organism Drosophila but, in 2013, they showed that some of the same molecular mechanisms for olfaction in fruit flies are used by mosquitoes to find human hosts. From that point on, Vosshall rapidly applied her vast expertise in bioengineering to unravel the brain circuits underlying the behavior of the mosquito Aedes aegypti. This mosquito is responsible for transmission of yellow fever, dengue fever, zika fever and more, making it one of the deadliest animals to humankind.

Mosquitoes have evolved to specifically prey on humans and transmit millions of cases of deadly diseases around the globe. Vosshall’s laboratory is filled with mosquitoes in which her team induces various gene mutations to identify the molecular circuits that mosquitoes use to hunt and feed on humans. In 2022, Vosshall received press around the world for identifying oils produced by the skin of some people that make them “mosquito magnets.” Vosshall further showed that olfactory receptors have an unusual distribution pattern within the antennae of mosquitoes that allow mosquitoes to detect a whole slew of human scents, in addition to their ability to detect human’s warmth and breath. Vosshall’s team has also unraveled the molecular basis for mosquitoes’ avoidance of DEET and identified a novel repellent and identified genes for how they choose where to lay eggs and resist drought. Vosshall’s brilliant application of genome engineering to understand a wide range of mosquito behaviors has profound implications for human health. Moreover, since shifting her research to the mosquito, seven postdoctoral researchers that Vosshall mentored have established their own mosquito research laboratories at Boston University, Columbia University, Yale University, Johns Hopkins University, Princeton University, Florida International University, and the University of British Columbia.

Vosshall’s professional service is remarkable – she has served on innumerable committees at Rockefeller University and has participated in outreach activities around the globe, even starring in the feature length film “The Fly Room.” She began serving as the Vice President and Chief Scientific Officer of HHMI in 2022 and previously served as Associate Director and Director of the Kavli Neural Systems Institute from 2015 to 2021. She has served as an editor for numerous journals, on the Board of Directors for the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation, the McKnight Foundation and more, and co-organized over a dozen conferences. Her achievements have been recognized by the Dickson Prize in Medicine (2024), the Perl-UNC Neuroscience Prize (2022), and the Pradel Research Award (2020). She is an elected member of the National Academy of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences, American Philosophical Society, and American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The McGovern Institute will award the Scolnick Prize to Vosshall on May 9, 2025. At 4:00 pm she will deliver a lecture titled “Mosquitoes: neurobiology of the world’s most dangerous animal” to be followed by a reception at the McGovern Institute, 43 Vassar Street (building 46, room 3002) in Cambridge. The event is free and open to the public.