An MIT senior and eight MIT graduate students are among the 30 recipients of this year’s P.D. Soros Fellowships for New Americans. In addition to senior Fiona Chen, MIT’s newest Soros winners include graduate students Aziza Almanakly, Alaleh Azhir, Brian Y. Chang PhD ’18, James Diao, Charlie ChangWon Lee, Archana Podury, Ashwin Sah ’20, and Enrique Toloza. Six of the recipients are enrolled at the Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology.

P.D. Soros Fellows receive up to $90,000 to fund their graduate studies and join a lifelong community of new Americans from different backgrounds and fields. The 2021 class was selected from a pool of 2,445 applicants, marking the most competitive year in the fellowship’s history.

The Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowships for New Americans program honors the contributions of immigrants and children of immigrants to the United States. As Fiona Chen says, “Being a new American has required consistent confrontation with the struggles that immigrants and racial minorities face in the U.S. today. It has meant frequent difficulties with finding security and comfort in new contexts. But it has also meant continual growth in learning to love the parts of myself — the way I look; the things that my family and I value — that have marked me as different, or as an outsider.”

Students interested in applying to the P.D. Soros fellowship should contact Kim Benard, assistant dean of distinguished fellowships in Career Advising and Professional Development.

Aziza Almanakly

Aziza Almanakly, a PhD student in electrical engineering and computer science, researches microwave quantum optics with superconducting qubits for quantum communication under Professor William Oliver in the Department of Physics. Almanakly’s career goal is to engineer multi-qubit systems that push boundaries in quantum technology.

Born and raised in northern New Jersey, Almanakly is the daughter of Syrian immigrants who came to the United States in the early 1990s in pursuit of academic opportunities. As the civil war in Syria grew dire, more of her relatives sought asylum in the U.S. Almanakly grew up around extended family who built a new version of their Syrian home in New Jersey.

Following in the footsteps of her mathematically minded father, Almanakly studied electrical engineering at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. She also pursued research opportunities in experimental quantum computing at Princeton University, the City University of New York, New York University, and Caltech.

Almanakly recognizes the importance of strong mentorship in diversifying engineering. She uses her unique experience as a New American and female engineer to encourage students from underrepresented backgrounds to enter STEM fields.

Alaleh Azhir

Alaleh Azhir grew up in Iran, where she pursued her passion for mathematics. She immigrated with her mother to the United States at age 14. Determined to overcome strict gender roles she had witnessed for women, Azhir is dedicated to improving health care for them.

Azhir graduated from Johns Hopkins University in 2019 with a perfect GPA as a triple major in biomedical engineering, computer science, and applied mathematics and statistics. A Rhodes and Barry Goldwater Scholar, she has developed many novel tools for visualization and analysis of genomics data at Johns Hopkins University, Harvard University, MIT, the National Institutes of Health, and laboratories in Switzerland.

After completing a master’s in statistical science at Oxford University, Azhir began her MD studies in the Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology. Her thesis focuses on the role of X and Y sex chromosomes on disease manifestations. Through medical training, she aims to build further computational tools specifically for preventive care for women. She has also founded and directs the nonprofit organization, Frappa, aimed at mentoring women living in Iran and helping them to immigrate abroad through the graduate school application process.

Brian Y. Chang PhD ’18

Born in Johnson City, New York, Brian Y. Chang PhD ’18 is the son of immigrants from the Shanghai municipality and Shandong Province in China. He pursued undergraduate and master’s degrees in mechanical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University, graduating in a combined four years with honors.

In 2018, Chang completed a PhD in medical engineering at MIT. Under the mentorship of Professor Elazer Edelman, Chang developed methods that make advanced cardiac technologies more accessible. The resulting approaches are used in hospitals around the world. Chang has published extensively and holds five patents.

With the goal of harnessing the power of engineering to improve patient care, Chang co-founded X-COR Therapeutics, a seed-funded medical device startup developing a more accessible treatment for lung failure with the potential to support patients with severe Covid-19 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

After spending time in the hospital connecting with patients and teaching cardiovascular pathophysiology to medical students, Chang decided to attend medical school. He is currently a medical student in the Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology. Chang hopes to advance health care through medical device innovation and education as a future physician-scientist, entrepreneur, and educator.

Fiona Chen

MIT senior Fiona Chen was born in Cedar Park, Texas, the daughter of immigrants from China. Witnessing how her own and many other immigrant families faced significant difficulties finding work and financial stability sparked her interest in learning about poverty and economic inequality.

At MIT, Chen has pursued degrees in economics and mathematics. Her economics research projects have examined important policy issues — social isolation among students, global development and poverty, universal health-care systems, and the role of technology in shaping the labor market.

An active member of the MIT community, Chen has served as the officer on governance and officer on policy of the Undergraduate Association, MIT’s student government; the opinion editor of The Tech student newspaper; the undergraduate representative of several Institute-wide committees, including MIT’s Corporation Joint Advisory Committee; and one of the founding members of MIT Students Against War. In each of these roles, she has worked to advocate for policies to support underrepresented groups at MIT.

As a Soros fellow, Chen will pursue a PhD in economics to deepen her understanding of economic policy. Her ultimate goal is to become a professor who researches poverty and economic inequality, and applies her findings to craft policy solutions.

James Diao

James Diao graduated from Yale University with degrees in statistics and biochemistry and is currently a medical student at the Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology. He aspires to give voice to patient perspectives in the development and evaluation of health-care technology.

Diao grew up in Houston’s Chinatown, and spent summers with his extended family in Jiangxian. Diao’s family later moved to Fort Bend, Texas, where he found a pediatric oncologist mentor who introduced him to the wonders of modern molecular biology.

Diao’s interests include the responsible development of technology. At Apple, he led projects to validate wearable health features in diverse populations; at PathAI, he built deep learning models to broaden access to pathologist services; at Yale, where he worked on standardizing analyses of exRNA biomarkers; and at Harvard, he studied the impacts of clinical guidelines on marginalized groups.

Diao’s lead author research in the New England Journal of Medicine and JAMA systematically compared race-based and race-free equations for kidney function, and demonstrated that up to 1 million Black Americans may receive unequal kidney care due to their race. He has also published articles on machine learning and precision medicine.

Charlie ChangWon Lee

Born in Seoul, South Korea, Charlie ChangWon Lee was 10 when his family immigrated to the United States and settled in Palisades Park, New Jersey. The stress of his parents’ lack of health coverage ignited Lee’s determination to study the reasons for the high cost of health care in the U.S. and learn how to care for uninsured families like his own.

Lee graduated summa cum laude in integrative biology from Harvard College, winning the Hoopes Prize for his thesis on the therapeutic potential of human gut microbes. Lee’s research on novel therapies led him to question how newly approved, and expensive, medications could reach more patients.

At the Program on Regulation, Therapeutics, and Law (PORTAL) at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Lee studied policy issues involving pharmaceutical drug pricing, drug development, and medication use and safety. His articles have appeared in JAMA, Health Affairs, and Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

As a first-year medical student at the Harvard-MIT Health Sciences and Technology program, Lee is investigating policies to incentivize vaccine and biosimilar drug development. He hopes to find avenues to bridge science and policy and translate medical innovations into accessible, affordable therapies.

Archana Podury

The daughter of Indian immigrants, Archana Podury was born in Mountain View, California. As an undergraduate at Cornell University, she studied the neural circuits underlying motor learning. Her growing interest in whole-brain dynamics led her to the Princeton Neuroscience Institute and Neuralink, where she discovered how brain-machine interfaces could be used to understand diffuse networks in the brain.

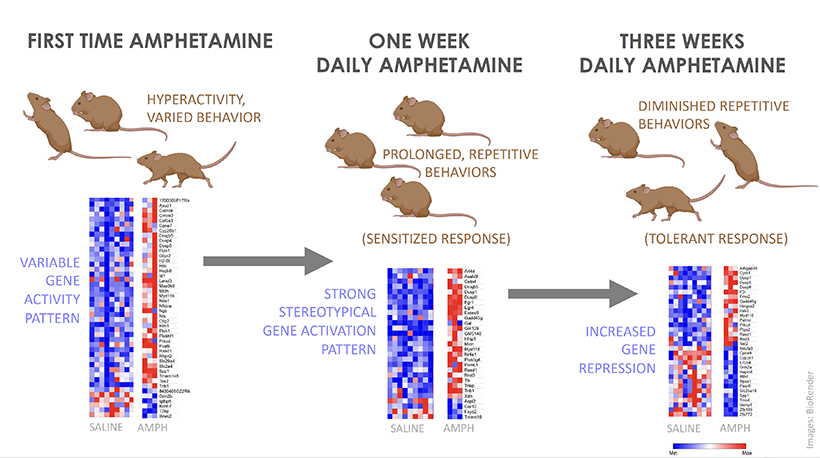

While studying neural circuits, Podury worked at a syringe exchange in Ithaca, New York, where she witnessed firsthand the mechanics of court-based drug rehabilitation. Now, as an MD student in the Harvard-MIT Health Sciences and Technology program, Podury is interested in combining computational and social approaches to neuropsychiatric disease.

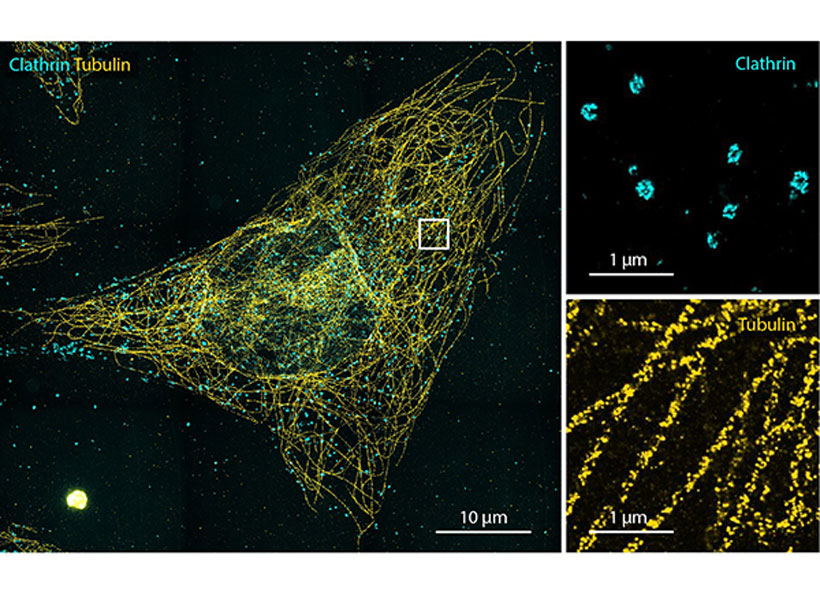

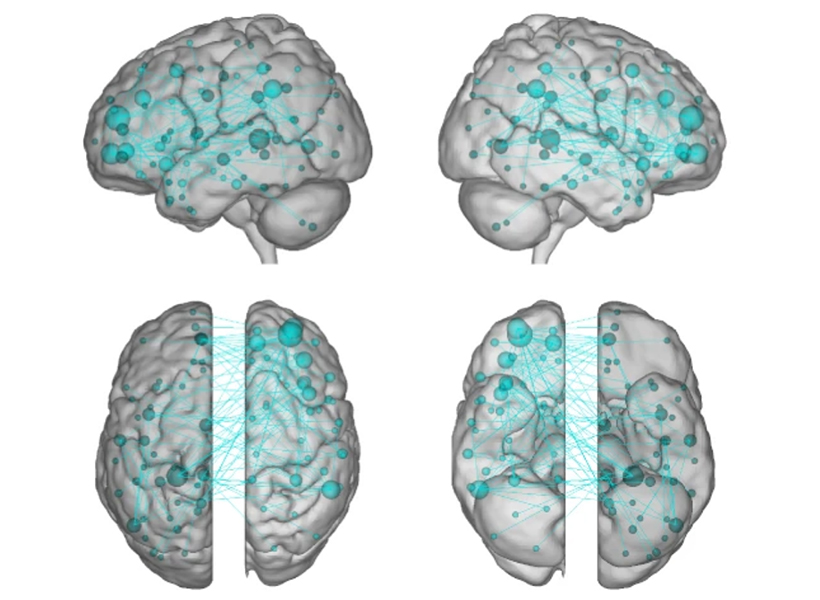

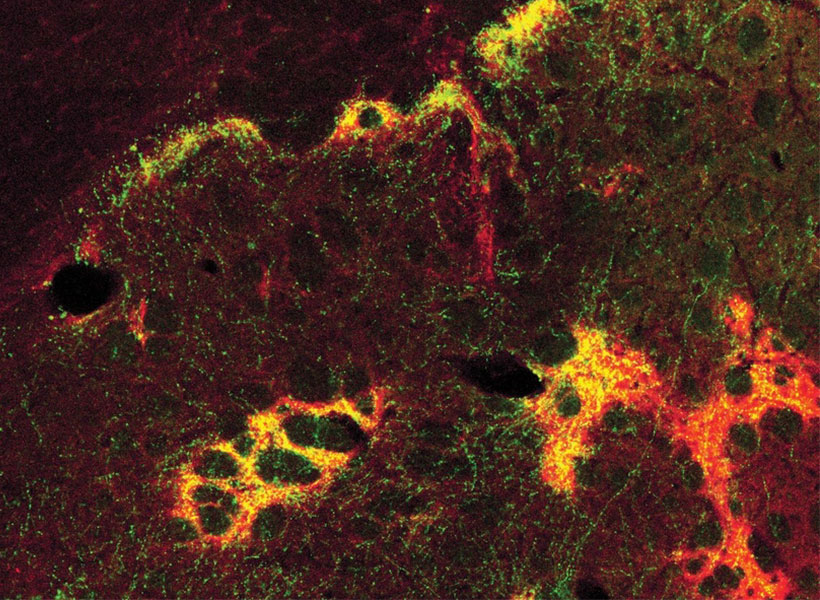

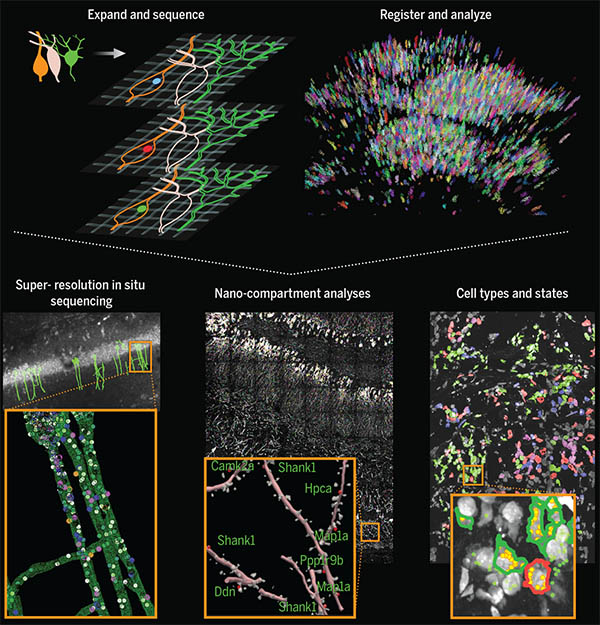

In the Boyden Lab at the MIT McGovern Institute for Brain Research, Podury is developing human brain organoid models to better characterize circuit dysfunction in neurodevelopmental disorders. Concurrently, her work in the Dhand Lab at Brigham and Women’s Hospital applies network science tools to understand how patients’ social environments influence their health outcomes following acute neurological injury.

Podury hopes that focusing on both neural and social networks can lead toward a more comprehensive, and compassionate, approach to health and disease.

Ashwin Sah ’20

Ashwin Sah ’20 was born and raised in Portland, Oregon, the son of Indian immigrants. He developed a passion for mathematics research as an undergraduate at MIT, where he conducted research under Professor Yufei Zhao, as well as at the Duluth and Emory REU (Research Experience for Undergraduates) programs.

Sah has given talks on his work at multiple professional venues. His undergraduate research in varied areas of combinatorics and discrete mathematics culminated in the Barry Goldwater Scholarship and the Frank and Brennie Morgan Prize for Outstanding Research in Mathematics by an Undergraduate Student. Additionally, his work on diagonal Ramsey numbers was recently featured in Quanta Magazine.

Beyond research, Sah has pursued opportunities to give back to the math community, helping to organize or grade competitions such as the Harvard-MIT Mathematics Tournament and the USA Mathematical Olympiad. He has also been a grader at the Mathematical Olympiad Program, a camp for talented high-school students in the United States, and an instructor for the Monsoon Math Camp, a virtual program aimed at teaching higher mathematics to high school students in India.

Sah is currently a PhD student in mathematics at MIT, where he continues to work with Zhao.

Enrique Toloza

Enrique Toloza was born in Los Angeles, California, the child of two immigrants: one from Colombia who came to the United States for a PhD and the other from the Philippines who grew up in California and went on to medical school. Their literal marriage of science and medicine inspired Toloza to become a physician-scientist.

Toloza majored in physics and Spanish literature at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He eventually settled on an interest in theoretical neuroscience after a summer research internship at MIT and completing an honors thesis on noninvasive brain stimulation.

After college, Toloza joined Professor Mark Harnett’s laboratory at MIT for a year. He went on to enroll in the Harvard-MIT MD/PhD program, studying within the Health Sciences and Technology MD curriculum at Harvard and the PhD program at MIT. For his PhD, Toloza rejoined Harnett to conduct research on the biophysics of dendritic integration and the contribution of dendrites to cortical computations in the brain.

Toloza is passionate about expanding health care access to immigrant populations. In college, he led the interpreting team at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s student-run health clinic; at Harvard Medical School, he has worked with Spanish-speaking patients as a student clinician.