From early development to old age, cell death is a part of life. Without enough of a critical type of cell death known as apoptosis, animals wind up with too many cells, which can set the stage for cancer or autoimmune disease. But careful control is essential, because when apoptosis eliminates the wrong cells, the effects can be just as dire, helping to drive many kinds of neurodegenerative disease.

By studying the microscopic roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans—which was honored with its fourth Nobel Prize last month—scientists at MIT’s McGovern Institute have begun to unravel a longstanding mystery about the factors that control apoptosis: how a protein capable of preventing programmed cell death can also promote it. Their study, led by McGovern Investigator Robert Horvitz and reported October 9, 2024, in the journal Science Advances, sheds light on the process of cell death in both health and disease.

“These findings, by graduate student Nolan Tucker and former graduate student, now MIT faculty colleague, Peter Reddien, have revealed that a protein interaction long thought to block apoptosis in C. elegans, likely instead has the opposite effect,” says Horvitz, who shared the 2002 Nobel Prize for discovering and characterizing the genes controlling cell death in C. elegans.

Mechanisms of cell death

Horvitz, Tucker, Reddien and colleagues have provided foundational insights in the field of apoptosis by using C. elegans to analyze the mechanisms that drive apoptosis as well as the mechanisms that determine how cells ensure apoptosis happens when and where it should. Unlike humans and other mammals, which depend on dozens of proteins to control apoptosis, these worms use just a few. And when things go awry, it’s easy to tell: When there’s not enough apoptosis, researchers can see that there are too many cells inside the worms’ translucent bodies. And when there’s too much, the worms lack certain biological functions or, in more extreme cases, can’t reproduce or die during embryonic development.

Work in the Horvitz lab defined the roles of many of the genes and proteins that control apoptosis in worms. These regulators proved to have counterparts in human cells, and for that reason studies of worms have helped reveal how human cells govern cell death and pointed toward potential targets for treating disease.

A protein’s dual role

Three of C. elegans’ primary regulators of apoptosis actively promote cell death, whereas just one, CED-9, reins in the apoptosis-promoting proteins to keep cells alive. As early as the 1990s, however, Horvitz and colleagues recognized that CED-9 was not exclusively a protector of cells. Their experiments indicated that the protector protein also plays a role in promoting cell death. But while researchers thought they knew how CED-9 protected against apoptosis, its pro-apoptotic role was more puzzling.

CED-9’s dual role means that mutations in the gene that encode it can impact apoptosis in multiple ways. Most ced-9 mutations interfere with the protein’s ability to protect against cell death and result in excess cell death. Conversely, mutations that abnormally activate ced-9 cause too little cell death, just like mutations that inactivate any of the three killer genes.

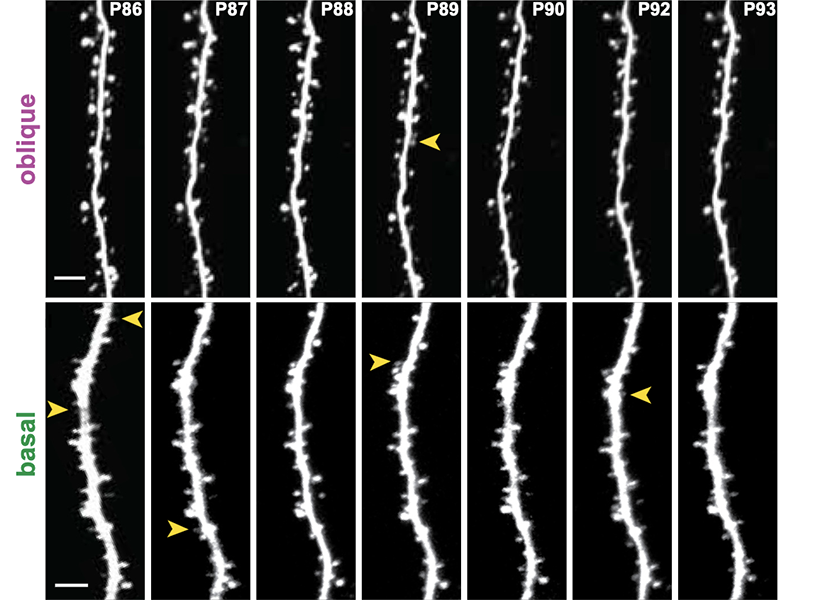

An atypical ced-9 mutation, identified by Reddien when he was a PhD student in Horvitz’s lab, hinted at how CED-9 promotes cell death. That mutation altered the part of the CED-9 protein that interacts with the protein CED-4, which is proapoptotic. Since the mutation specifically leads to a reduction in apoptosis, this suggested that CED-9 might need to interact with CED-4 to promote cell death.

The idea was particularly intriguing because researchers had long thought that CED-9’s interaction with CED-4 had exactly the opposite effect: In the canonical model, CED-9 anchors CED-4 to cells’ mitochondria, sequestering the CED-4 killer protein and preventing it from associating with and activating another key killer, the CED-3 protein —thereby preventing apoptosis.

To test the hypothesis that CED-9’s interactions with the killer CED-4 protein enhance apoptosis, the team needed more evidence. So graduate student Nolan Tucker used CRISPR gene editing tools to create more worms with mutations in CED-9, each one targeting a different spot in the CED-4-binding region. Then he examined the worms. “What I saw with this particular class of mutations was extra cells and viability,” he says—clear signs that the altered CED-9 was still protecting against cell death, but could no longer promote it. “Those observations strongly supported the hypothesis that the ability to bind CED-4 is needed for the pro-apoptotic function of CED-9,” Tucker explains. Their observations also suggested that, contrary to earlier thinking, CED-9 doesn’t need to bind with CED-4 to protect against apoptosis.

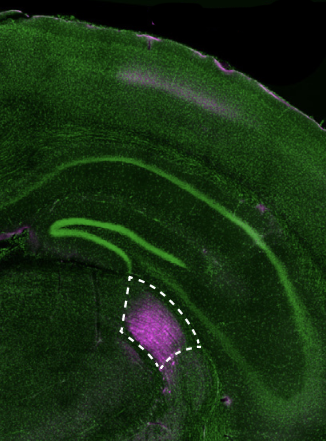

When he looked inside the cells of the mutant worms, Tucker found additional evidence that these mutations prevented CED-9’s ability to interact with CED-4. When both CED-9 and CED-4 are intact, CED-4 appears associated with cells’ mitochondria. But in the presence of these mutations, CED-4 was instead at the edge of the cell nucleus. CED-9’s ability to bind CED-4 to mitochondria appeared to be necessary to promote apoptosis, not to protect against it.

Looking ahead

While the team’s findings begin to explain a long-unanswered question about one of the primary regulators of apoptosis, they raise new ones, as well. “I think that this main pathway of apoptosis has been seen by a lot of people as more or less settled science. Our findings should change that view,” Tucker says.

The researchers see important parallels between their findings from this study of worms and what’s known about cell death pathways in mammals. The mammalian counterpart to CED-9 is a protein called BCL-2, mutations in which can lead to cancer. BCL-2, like CED-9, can both promote and protect against apoptosis. As with CED-9, the pro-apoptotic function of BCL-2 has been mysterious. In mammals, too, mitochondria play a key role in activating apoptosis. The Horvitz lab’s discovery opens opportunities to better understand how apoptosis is regulated not only in worms but also in humans, and how dysregulation of apoptosis in humans can lead to such disorders as cancer, autoimmune disease and neurodegeneration.