Parkinson’s disease is best-known as a disorder of movement. Patients often experience tremors, loss of balance, and difficulty initiating movement. The disease also has lesser-known symptoms that are nonmotor, including depression.

In a study of a small region of the thalamus, MIT neuroscientists have now identified three distinct circuits that influence the development of both motor and nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s. Furthermore, they found that by manipulating these circuits, they could reverse Parkinson’s symptoms in mice.

The findings suggest that those circuits could be good targets for new drugs that could help combat many of the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, the researchers say.

“We know that the thalamus is important in Parkinson’s disease, but a key question is how can you put together a circuit that that can explain many different things happening in Parkinson’s disease. Understanding different symptoms at a circuit level can help guide us in the development of better therapeutics,” says Guoping Feng, the James W. and Patricia T. Poitras Professor in Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT, a member of the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, and the associate director of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT.

Feng is the senior author of the study, which appears today in Nature. Ying Zhang, a J. Douglas Tan Postdoctoral Fellow at the McGovern Institute, and Dheeraj Roy, a NIH K99 Awardee and a McGovern Fellow at the Broad Institute, are the lead authors of the paper.

Tracing circuits

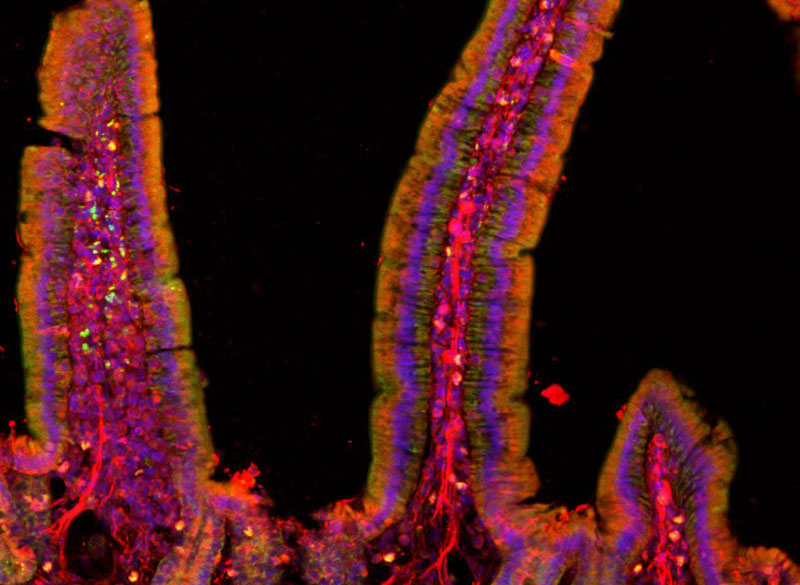

The thalamus consists of several different regions that perform a variety of functions. Many of these, including the parafascicular (PF) thalamus, help to control movement. Degeneration of these structures is often seen in patients with Parkinson’s disease, which is thought to contribute to their motor symptoms.

In this study, the MIT team set out to try to trace how the PF thalamus is connected to other brain regions, in hopes of learning more about its functions. They found that neurons of the PF thalamus project to three different parts of the basal ganglia, a cluster of structures involved in motor control and other functions: the caudate putamen (CPu), the subthalamic nucleus (STN), and the nucleus accumbens (NAc).

“We started with showing these different circuits, and we demonstrated that they’re mostly nonoverlapping, which strongly suggests that they have distinct functions,” Roy says.

Further studies revealed those functions. The circuit that projects to the CPu appears to be involved in general locomotion, and functions to dampen movement. When the researchers inhibited this circuit, mice spent more time moving around the cage they were in.

The circuit that extends into the STN, on the other hand, is important for motor learning — the ability to learn a new motor skill through practice. The researchers found that this circuit is necessary for a task in which the mice learn to balance on a rod that spins with increasing speed.

Lastly, the researchers found that, unlike the others, the circuit that connects the PF thalamus to the NAc is not involved in motor activity. Instead, it appears to be linked to motivation. Inhibiting this circuit generates depression-like behaviors in healthy mice, and they will no longer seek a reward such as sugar water.

Druggable targets

Once the researchers established the functions of these three circuits, they decided to explore how they might be affected in Parkinson’s disease. To do that, they used a mouse model of Parkinson’s, in which dopamine-producing neurons in the midbrain are lost.

They found that in this Parkinson’s model, the connection between the PF thalamus and the CPu was enhanced, and that this led to a decrease in overall movement. Additionally, the connections from the PF thalamus to the STN were weakened, which made it more difficult for the mice to learn the accelerating rod task.

Lastly, the researchers showed that in the Parkinson’s model, connections from the PF thalamus to the NAc were also interrupted, and that this led to depression-like symptoms in the mice, including loss of motivation.

Using chemogenetics or optogenetics, which allows them to control neuronal activity with a drug or light, the researchers found that they could manipulate each of these three circuits and in doing so, reverse each set of Parkinson’s symptoms. Then, they decided to look for molecular targets that might be “druggable,” and found that each of the three PF thalamus regions have cells that express different types of cholinergic receptors, which are activated by the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. By blocking or activating those receptors, depending on the circuit, they were also able to reverse the Parkinson’s symptoms.

“We found three distinct cholinergic receptors that can be expressed in these three different PF circuits, and if we use antagonists or agonists to modulate these three different PF populations, we can rescue movement, motor learning, and also depression-like behavior in PD mice,” Zhang says.

Parkinson’s patients are usually treated with L-dopa, a precursor of dopamine. While this drug helps patients regain motor control, it doesn’t help with motor learning or any nonmotor symptoms, and over time, patients become resistant to it.

The researchers hope that the circuits they characterized in this study could be targets for new Parkinson’s therapies. The types of neurons that they identified in the circuits of the mouse brain are also found in the nonhuman primate brain, and the researchers are now using RNA sequencing to find genes that are expressed specifically in those cells.

“RNA-sequencing technology will allow us to do a much more detailed molecular analysis in a cell-type specific way,” Feng says. “There may be better druggable targets in these cells, and once you know the specific cell types you want to modulate, you can identify all kinds of potential targets in them.”

The research was funded, in part, by the K. Lisa Yang and Hock E. Tan Center for Molecular Therapeutics in Neuroscience at MIT, the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad Institute, the James and Patricia Poitras Center for Psychiatric Disorders Research at MIT, the National Institutes of Health BRAIN Initiative, and the National Institute of Mental Health.