Over several decades, neuroscientists have created a well-defined map of the brain’s “language network,” or the regions of the brain that are specialized for processing language. Found primarily in the left hemisphere, this network includes regions within Broca’s area, as well as in other parts of the frontal and temporal lobes. Although roughly 7,000 languages are currently spoken and signed across the globe, the vast majority of those mapping studies have been done in English speakers as they listened to or read English texts.

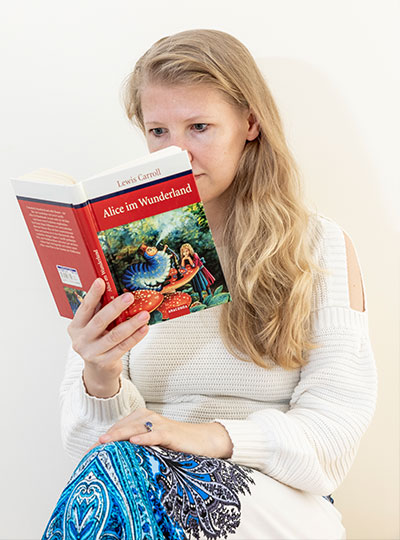

To truly understand the cognitive and neural mechanisms that allow us to learn and process such diverse languages, Fedorenko and her team scanned the brains of speakers of 45 different languages while they listened to Alice in Wonderland in their native language. The results show that the speakers’ language networks appear to be essentially the same as those of native English speakers — which suggests that the location and key properties of the language network appear to be universal.

English may be the primary language used by McGovern researchers, but more than 35 other languages are spoken by scientists and engineers at the McGovern Institute. Our holiday video features 30 of these researchers saying Happy New Year in their native (or learned) language. Below is the complete list of languages included in our video. Expand each accordion to learn more about the speaker of that particular language and the meaning behind their new year’s greeting.

American Sign Language

Kian Caplan (Feng lab)

Nationality: American

Other languages spoken: English

American Sign Language (ASL) serves as the predominant sign language of Deaf communities in the United States and most of English-speaking Canada. Imaging studies have shown that ASL activates the brain’s language network in the same way that spoken languages do.

“In high school, I had a teacher who was fluent in ASL and exposed me to the beautiful language,” says Kaplan. “She inspired me to take three semesters of ASL in college, taught by a professor who was hard of hearing. It wasn’t until then that I began to appreciate Deaf history and culture, and had the opportunity to communicate with members of this wonderful community.”

Caplan goes on to explain that “ASL is not signed English, it is a different language with its own sets of grammar rules. Across the US, there are accents of sign language just like spoken languages, such as variations in signs used. Each country also has their own sign language, it is not universal (although there is technically a “Universal Sign Language”).”

Arabic

Ubadah Sabbagh (Feng lab)

Nationality: Syrian

Other languages spoken: English

Personal webpage

Arabic, Sabbagh’s first language, is a Semitic language spoken across a large area including North Africa, most of the Arabian Peninsula, and other parts of the Middle East.

“Since this McGovern project is on language, I’d like to share a verse from one of my favorite Arabic poets, Mahmoud Darwish,” says Sabbagh. “He wrote on his relationship to language, and addressing it directly he said,

يا لغتي ساعديني على الاقتباس لأحتضن الكون.

يا لغتي! هل أكون أنا ما تكونين؟ أم أنت – يا لغتي – ما أكون؟

‘O my language, empower me to learn and so that I may embrace the universe.

O my language, will I become what you’ll become, or are you what becomes of me?'”

Bengali

Kohitij “Ko” Kar (DiCarlo lab)

Nationality: Indian

Other languages spoken: English, Hindi

Bengali, or Bangla, is an Indo-Aryan language native to the Bengal region of South Asia. It is the official, national, and most widely spoken language of Bangladesh and the second most widely spoken of the 22 scheduled languages of India.

“Like many other regional languages (and nations) around the world, Bengalis also have their own calendar. We are still in 1429 🙂 So the greeting I spoke is used a lot during our new year day, which is usually on April 15 (India), April 14 (Bangladesh),” says Kar.

Cantonese

Karen Pang (Anikeeva lab)

Nationality: Chinese (Hong Kong)

Other languages spoken: English, Mandarin

Like other Chinese dialects, Cantonese uses different tones to distinguish words. “Cantonese has nine tones,” says Pang, who was born and raised in Hong Kong.

Danish

Greta Tuckute (Fedorenko lab)

Nationality: Lithuanian and Danish

Other languages spoken: English, French, Lithuanian

“Right before midnight, most Danes will climb up on chairs, tables, or pretty much any elevated surface in order to jump down from it when the clock strikes twelve,” says Tuckute, who was born in Lithuana and moved to Denmark at age two. “It is considered good luck to ‘jump’ into the new year.”

Dothraki

Jessica Chomik-Morales (Kanwisher lab)

Nationality: American

Other languages spoken: English, Spanish

Dothraki is the constructed language (conlang) from the fantasy novel series “A Song of Ice and Fire” and its television adaptation “Game of Thrones.” It is spoken by the Dothraki, a nomadic people in the series’s fictional world. The Fedorenko lab has found that conlangs activate the language network the same way natural languages do.

“I have loved ‘Game of Thrones’ since reading the series in the sixth grade,” says Chomik-Morales. “The Dothraki are these incredible, ferocious warriors that fight on horseback in this fictional world and I can imagine they’d know how to throw a good celebration for New Year’s.”

French

Antoine De Comité (Seethapathi lab)

Nationality: Belgian

Other languages spoken: Dutch, English

“The French language has a lot of funny features,” says De Comité. “Almost all the time, we don’t pronounce the letter ‘h’ when it’s in a word. Also, there is no genuine word with a ‘w’ in French, they’re all borrowed from other languages.”

German

Marie Manthey (Anikeeva lab)

Nationality: German

Other languages spoken: English, French (beginner), Spanish (beginner)

“In Germany, depending on where you are living and what dialect you are speaking we have slightly different sayings for Happy New Year,” explains Manthey. “My family is from around Hamburg and north-west Lower Saxony, where ‘Prosit Neujahr’ is more typical. One thing that is a tradition in my family and in many German families is to watch the show ‘Dinner for One’ on New Year’s Eve. It’s a 15-minute British comedy sketch from the 1960’s about a woman named Miss Sophie who celebrates her 90th birthday by inviting her four closest friends to dinner. However, Miss Sophie has outlived all of these friends, so her butler James is forced to impersonate the guests throughout the four course meal. ‘Dinner for One’ is not really well known in Great Britain, but it airs on New Year’s Eve in German speaking countries and Scandinavia.

Greek

Konstantinos Kagias (Boyden lab)

Nationality: Greek

Other languages spoken: English, French

Greek, the official language of Greece and Cyprus, has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning thousands of years of written records.

“Each of the main words in the Greek New Year’s greeting ‘Καλη Χρονια Σε Όλους’ is the root word of few English words,” says Kagias, who has spoken the language his whole life. “Examples include calisthenics, California, chronology, chronic, and holistic.”

Hebrew

Tamar Regev (Fedorenko lab)

Nationality: Israeli

Other languages spoken: English, Spanish

“The new Jewish year is actually around September and is called ‘Rosh HaShana,’ or head of the year,” explains Regev. “This is when we say Shana Tova, eat pomegranates and apple with honey (to make the new year sweet).”

Hindi

Sugandha “Su” Sharma (Fiete/Tenenbaum labs)

Nationality: Indian, Canadian

Other languages spoken: English, Punjabi

Hindi is the preferred official language of India and is spoken as a first language by nearly 425 million people and as a second language by some 120 million more. Sharma was born and raised in India (specifically Amritsar, Punjab), and her family spoke both Hindi and Punjabi. She also learned both languages in school while growing up.

Irish (Gaeilge)

Maedbh King (Ghosh lab)

Nationality: Irish

Other languages spoken: English, French (intermediate), German (beginner)

“Although Irish is an official language of Ireland, it is not spoken by a majority of people on a day-to-day basis,” explains King. “However, Irish is taught in schools from kindergarten through high school so most people have a basic understanding of the language. I attended Irish immersion schools through high school as did most of my immediate and extended family on my mom’s side. There are certain regions of the country, known as ‘Gaeltachts’, where Irish is the primary language of the people. If you visit these regions, it is common to hear the language spoken by all members of the community, and road signs are generally only in Irish, which can be confusing for tourists!”

“The phrase I spoke in the video, ‘Go mbeirimid beo ag an am seo arís,’ directly translates to ‘May we live to see this time again next year.‘ It would typically be written on a New Year’s greeting card, or more commonly spoken as a New Year’s toast after one (or two or three) beers.”

Italian

Michelangelo “Michi” Naim (Yang lab)

Nationality: Italian

Other languages spoken: English, Hebrew

Personal webpage

“Italian is a beautiful language with its rolled r’s, round vowels, and melodic rhythm,” says Naim. “We celebrate the New Year with a big dinner (we constantly think about food) and we light fireworks at midnight and drink Prosecco.”

Japanese

Atsushi Takahashi (Martinos Imaging Center)

Nationality: Canadian, American

Other languages spoken: English, French, Danish (beginner), Mandarin (beginner)

The Japanese language is spoken natively by about 128 million people, primarily by Japanese people and primarily in Japan, the only country where it is the national language. Takahashi, who was born in Ireland, learned Japanese from his father.

Kashmiri

Saima Malik Moraleda (Fedorenko lab)

Nationality: Spanish

Other languages spoken: Arabic (beginner), Catalan, English, French, Hindi/Urdu, Spanish

Kashmiri is spoken in Kashmir, a region split between India and Pakistan in the northwestern Indian subcontinent.

“While Kashmiri is spoken by approximately 8 million people, only a small percentage knows how to read and write it,” says Moraleda, whose father spoke Kashmiri in her childhood home. “I was lucky that Harvard started offering a Kashmiri course last year, so I’ve finally started to learn to read a language I have known since I was born,” she adds. “There are three different scripts for it, none of which are standardized. I ended up picking the Romanized script for the greeting since that’s what the youth use when texting.”

Klingon

Maya Taliaferro (Fedorenko lab)

Nationality: American

Other languages spoken: English, Japanese

Klingon is the constructed language (conlang) spoken by the Klingons in the the Star Trek universe. As a conlang, Klingon has no real regional specificity and therefore has speakers from all over the world. Where there are fans of Star Trek there can be Klingon speakers. Fictionally, however, it originates on the planet Qo’noS where the Klingon people are from. The Fedorenko lab has found that conlangs activate the language network the same way natural languages do.

“While Klingon is a relatively niche language with an estimated 50-60 fluent speakers, anyone can learn it by taking a course on Duolingo/joining the Klingon Language Institute,” says Taliaferro, whose father is a “huge fan” of Star Trek.

Konkani

Rahul Brito (Ghosh lab)

Nationality: American

Other languages spoken: English, French (beginner)

Konkani is primarily spoken in Konkan, India which includes parts of modern states on the west coast of India such as Goa, Karnataka, Maharashtra, and Kerala. Although Brito’s extended family speaks Konkani, he actually does not speak it himself.

“To learn how to say ‘happy new year,’ I had to ask my mom (who did not remember), my aunt in India (who did not know for sure), and then her friend (who sent me a voice recording),” says Brito.

Korean

Jaeyoung Yoon (Harnett lab)

Nationality: Korean

Other languages spoken: English, Italian (beginner)

Korean is the native language for about 80 million people, mostly of Korean descent. Yoon was born in South Korea and has spoken the language his entire life.

Mandarin

Yiting “Veronica” Su (Desimone lab)

Nationality: Chinese

Other languages spoken: English

Chinese New Year, also called Lunar New Year, is an annual 15-day festival in China and Chinese communities around the world that begins with the new moon that occurs sometime between January 21 and February 20 according to Western calendars. Festivities last until the following full moon.

“In my culture, we celebrate the new year by cleaning and decorating the house with red things, offering sacrifices to ancestors, exchanging red envelopes and other gifts, watching lion and dragon dances, and of course, eating food at family reunion dinners!”

Marathi

Aalok Sathe (Fedorenko lab)

Nationality: Indian

Other languages spoken: English, Hindi, Sanskrit

Marathi is an Indo-Aryan language predominantly spoken in the central-west and coastal regions of India.

“We typically celebrate the new year in March/April by raising a gudhi in a window or a balcony of the home and by drawing colorful rangoli on the floor outside of entrances to homes and other establishments like schools and offices,” says Sathe. “The gudhi is a kind of flag made from a long wooden stick with a festive cloth, mango and neem leaves, marigold flowers, sugar crystals, and an upside-down silver/copper vessel on top to hold everything in place. This day also symbolizes the day Rama returned from a 14-year exile after defeating Ravana. Rama was a king whose dynasty and story (Ramayana) finds mention in mythologies of many cultures of South and East Asia including India, Nepal, Tibet, Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, and more. Some also consider this the day Brahma created the universe.”

Marwari

Vinayak “Vin” Agarwal (McDermott lab)

Nationality: Indian

Other languages spoken: English, Hindi

Marwari is spoken in the Indian state of Rajasthan, where Agarwal grew up. Rajasthan is the largest Indian state by area and is located on India’s northwestern side, where it comprises most of the Thar Desert, or Great Indian Desert.

Nepali

Sujaya Neupane (Jazayeri lab)

Nationality: Nepalese, Canadian

Other languages spoken: English, Hindi

Nepali is an Indo-Aryan language native to the Himalayas region of South Asia. It is the official, and most widely spoken, language of Nepal, where Neupane was born and raised.

Persian (Farsi)

Yasaman Bagherzadeh (Desimone lab)

Nationality: Iranian

Other languages spoken: English

Persian language or Farsi is spoken in Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. In Iran, 68% of the population speaks Persian as a first language.

“The new year and the first day of the Iranian calendar is different from most parts of the world,” explains Bagherzadeh. “The first day of the Iranian calendar falls on the March equinox, the first day of spring, around 21 March. We call it ‘Nowruz’ which means new day. The day of Nowruz has its origins in the Iranian religion of Zoroastrianism and is thus rooted in the traditions of the Iranian people for over 3,000 years. We celebrate Nowruz by cleaning our house (we call it home shaking), buying new clothes for the new year, visiting friends and family, and food preparation. Instead of a Christmas tree, we have 7-sin. Typically, before the arrival of Nowruz, family members gather around the Haft-sin table and await the exact moment of the March equinox to celebrate the New Year. The number 7 and the letter S are related to the seven Ameshasepantas as mentioned in the Zend-Avesta. They relate to the four elements of Fire, Earth, Air, Water, and the three life forms of Humans, Animals and Plants.”

Polish

Julia Dziubek (Harnett lab)

Nationality: Polish

Other languages spoken: English, German

“In Poland, we believe that the way you spend the last twelve days of your year will represent how you will spend the twelve months of the new year,” explains Dziubek. “For people who do not spend their last 12 days well, we have another belief,” she adds. “The way you spend your New Year’s Eve will determine how you will spend your new year.”

Portuguese

Willian De Faria (Kanwisher lab)

Nationality: Brazilian

Other languages spoken: English, Spanish

Portuguese is a western Romance language originating in the Iberian Peninsula of Europe. Approximately 274 million people speak Portuguese and is usually listed as the sixth-most spoken language in the world. Today, Portuguese is spoken in the Iberian peninsula, South America, and parts of Africa. The countries where Portuguese is spoken as the primary native languages are Portugal, Brazil, Angola, and São Tomé e Príncipe. However, Portuguese is the primary administrative language of many other countries like Mozambique and Cabo Verde.

“Fun fact,” says De Faria, who was born in Brazil and lived there until he was six. “It is easier for Portuguese native speakers to learn Spanish than the other way around. Also, Portuguese is a well represented language in New England! Aside from immigrants from Portugal, lots of lusophone communities have called Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut home. Many of these communities have Brazilian and Cabo Verdean origins. To note, Cabo Verdeans speak a beautiful Portuguese-based creole.”

Russian

Elvira Kinzina (AbuGoot lab)

Nationality: Russian

Other languages spoken: Arabic (beginner), English

Russian is an East Slavic language mainly spoken across Russia with over 258 million total speakers worldwide.

Saint Lucian Creole French (Kwéyòl)

Quilee Simeon (Yang lab)

Nationality: Saint Lucian

Other languages spoken: English

Saint Lucian Creole French (Kwéyòl), known locally as Patwa, is the French-based Creole widely spoken in Saint Lucia, where Simeon was born. It is the vernacular language of the country and is spoken alongside the official language of English. Though Kwéyòl is not an official language, the government and media houses present information in Kwéyòl, alongside English.

Spanish

Raul Mojica Soto-Albors (Harnett lab)

Nationality: Puerto Rican, American

Other languages spoken: English

“In Puerto Rico, most people speak Spanglish – a combination of Spanish and English,” explains Soto-Albors, who was born in Puerto Rico. “We constantly switch words up in a single sentence when speaking, with a seemingly arbitrary yet consistent set of rules.”

Regarding his new year’s greeting, Soto-Albors says, “it is common (more as a courtesy for acquaintances, service workers, and anyone you won’t see until after the new year) for people to wish each other ‘Feliz navidad y próspero año nuevo,’ which roughly translates to ‘Merry Christmas and Happy New Year,’ or, literally, ‘Merry Christmas and have a prosperous new year.’

Tamil

Karthik Srinivasan (Desimone lab)

Nationality: Indian

Other languages spoken: English, Hindi, and to varying degrees of comprehension and spoken ability Malayalam, Telugu, and Kannada (the other three major languages of the Dravidian language family)

Tamil is a Dravidian language natively spoken by the Tamil people of South Asia. Roughly 70 million people are native Tamil speakers. Tamil is an official language of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, the sovereign nations of Sri Lanka and Singapore, and the Indian territory of Puducherry. According to Srinivasan, “Tamil is one of the classical languages of India with literature dating back to antiquity and before (~atleast 1500 BCE if not earlier). It is possibly the oldest continuously spoken civilizational language and culture in the world with written records.”

Urdu

Syed Suleman Abbas Zaidi

Nationality: Pakistani

Other languages spoken: English

Urdu is an Indo-Aryan language spoken chiefly in South Asia. It is the national language of Pakistan, where it is also an official language alongside English. Similar to celebrations in the United States, Pakistanis ring in the new year with lots of fireworks, says Zaidi.