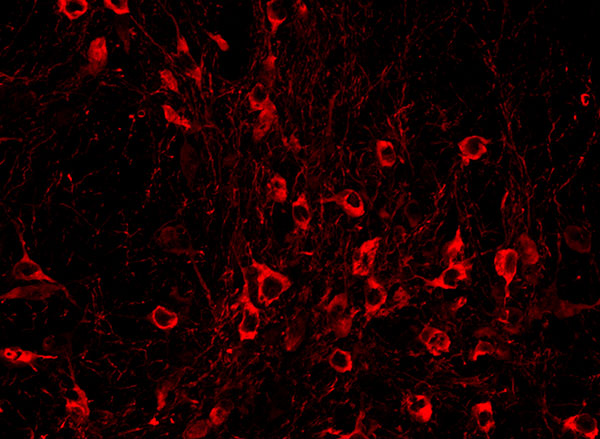

Scientists often label cells with proteins that glow, allowing them to track the growth of a tumor, or measure changes in gene expression that occur as cells differentiate.

While this technique works well in cells and some tissues of the body, it has been difficult to apply this technique to image structures deep within the brain, because the light scatters too much before it can be detected.

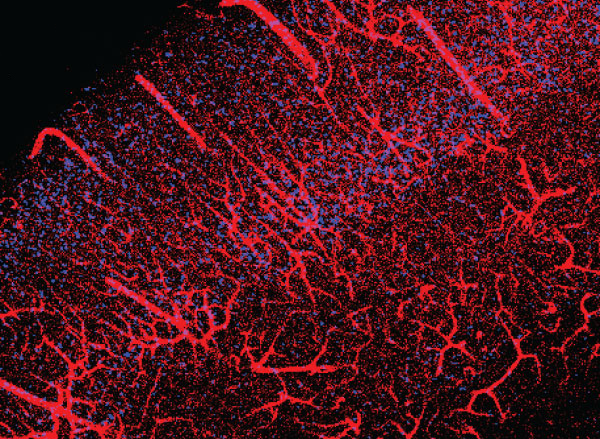

MIT engineers have now come up with a novel way to detect this type of light, known as bioluminescence, in the brain: They engineered blood vessels of the brain to express a protein that causes them to dilate in the presence of light. That dilation can then be observed with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), allowing researchers to pinpoint the source of light.

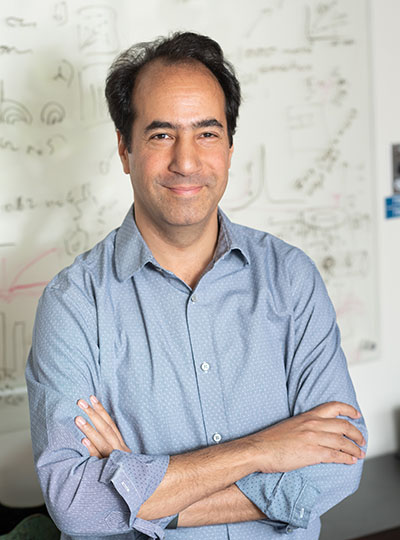

“A well-known problem that we face in neuroscience, as well as other fields, is that it’s very difficult to use optical tools in deep tissue. One of the core objectives of our study was to come up with a way to image bioluminescent molecules in deep tissue with reasonably high resolution,” says Alan Jasanoff, an MIT professor of biological engineering, brain and cognitive sciences, and nuclear science and engineering.

The new technique developed by Jasanoff and his colleagues could enable researchers to explore the inner workings of the brain in more detail than has previously been possible.

Jasanoff, who is also an associate investigator at MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research, is the senior author of the study, which appears today in Nature Biomedical Engineering. Former MIT postdocs Robert Ohlendorf and Nan Li are the lead authors of the paper.

Detecting light

Bioluminescent proteins are found in many organisms, including jellyfish and fireflies. Scientists use these proteins to label specific proteins or cells, whose glow can be detected by a luminometer. One of the proteins often used for this purpose is luciferase, which comes in a variety of forms that glow in different colors.

Jasanoff’s lab, which specializes in developing new ways to image the brain using MRI, wanted to find a way to detect luciferase deep within the brain. To achieve that, they came up with a method for transforming the blood vessels of the brain into light detectors. A popular form of MRI works by imaging changes in blood flow in the brain, so the researchers engineered the blood vessels themselves to respond to light by dilating.

“Blood vessels are a dominant source of imaging contrast in functional MRI and other non-invasive imaging techniques, so we thought we could convert the intrinsic ability of these techniques to image blood vessels into a means for imaging light, by photosensitizing the blood vessels themselves,” Jasanoff says.

“We essentially turn the vasculature of the brain into a three-dimensional camera.” – Alan Jasanoff

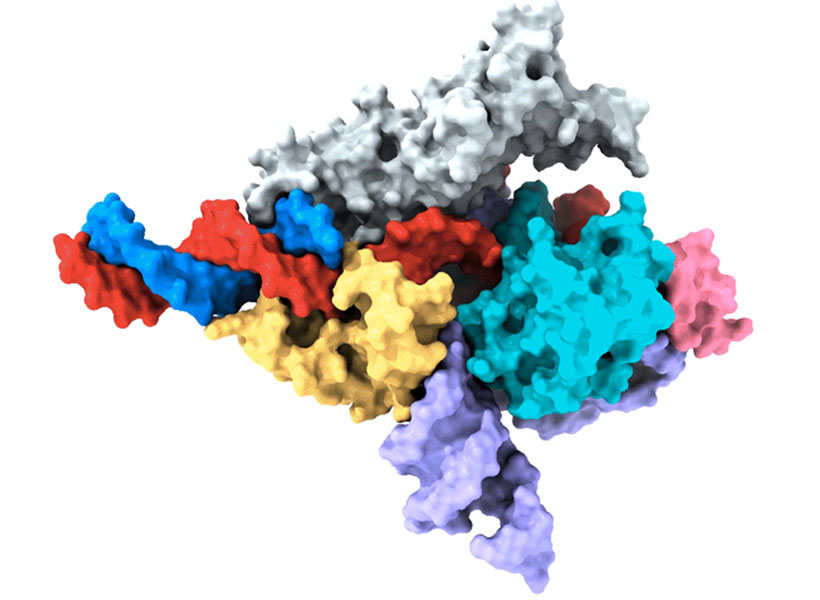

To make the blood vessels sensitive to light, the researcher engineered them to express a bacterial protein called Beggiatoa photoactivated adenylate cyclase (bPAC). When exposed to light, this enzyme produces a molecule called cAMP, which causes blood vessels to dilate. When blood vessels dilate, it alters the balance of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin, which have different magnetic properties. This shift in magnetic properties can be detected by MRI.

BPAC responds specifically to blue light, which has a short wavelength, so it detects light generated within close range. The researchers used a viral vector to deliver the gene for bPAC specifically to the smooth muscle cells that make up blood vessels. When this vector was injected in rats, blood vessels throughout a large area of the brain became light-sensitive.

“Blood vessels form a network in the brain that is extremely dense. Every cell in the brain is within a couple dozen microns of a blood vessel,” Jasanoff says. “The way I like to describe our approach is that we essentially turn the vasculature of the brain into a three-dimensional camera.”

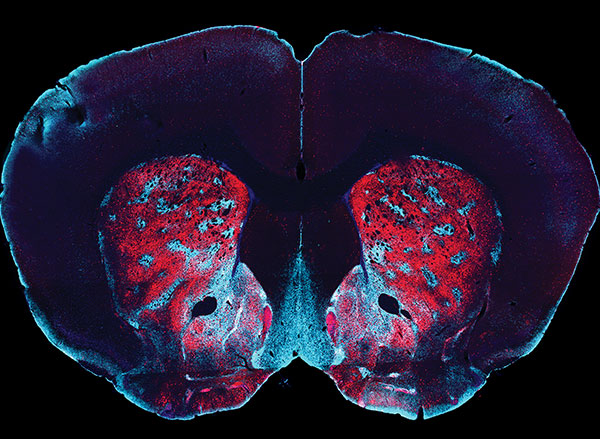

Once the blood vessels were sensitized to light, the researchers implanted cells that had been engineered to express luciferase if a substrate called CZT is present. In the rats, the researchers were able to detect luciferase by imaging the brain with MRI, which revealed dilated blood vessels.

Tracking changes in the brain

The researchers then tested whether their technique could detect light produced by the brain’s own cells, if they were engineered to express luciferase. They delivered the gene for a type of luciferase called GLuc to cells in a deep brain region known as the striatum. When the CZT substrate was injected into the animals, MRI imaging revealed the sites where light had been emitted.

This technique, which the researchers dubbed bioluminescence imaging using hemodynamics, or BLUsH, could be used in a variety of ways to help scientists learn more about the brain, Jasanoff says.

For one, it could be used to map changes in gene expression, by linking the expression of luciferase to a specific gene. This could help researchers observe how gene expression changes during embryonic development and cell differentiation, or when new memories form. Luciferase could also be used to map anatomical connections between cells or to reveal how cells communicate with each other.

The researchers now plan to explore some of those applications, as well as adapting the technique for use in mice and other animal models.

The research was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Foundation, Lore Harp McGovern, Gardner Hendrie, a fellowship from the German Research Foundation, a Marie Sklodowska-Curie Fellowship from the European Union, and a Y. Eva Tan Fellowship and a J. Douglas Tan Fellowship, both from the McGovern Institute for Brain Research.