Novel magnetic nanodiscs could provide a much less invasive way of stimulating parts of the brain, paving the way for stimulation therapies without implants or genetic modification, MIT researchers report.

The scientists envision that the tiny discs, which are about 250 nanometers across (about 1/500 the width of a human hair), would be injected directly into the desired location in the brain. From there, they could be activated at any time simply by applying a magnetic field outside the body. The new particles could quickly find applications in biomedical research, and eventually, after sufficient testing, might be applied to clinical uses.

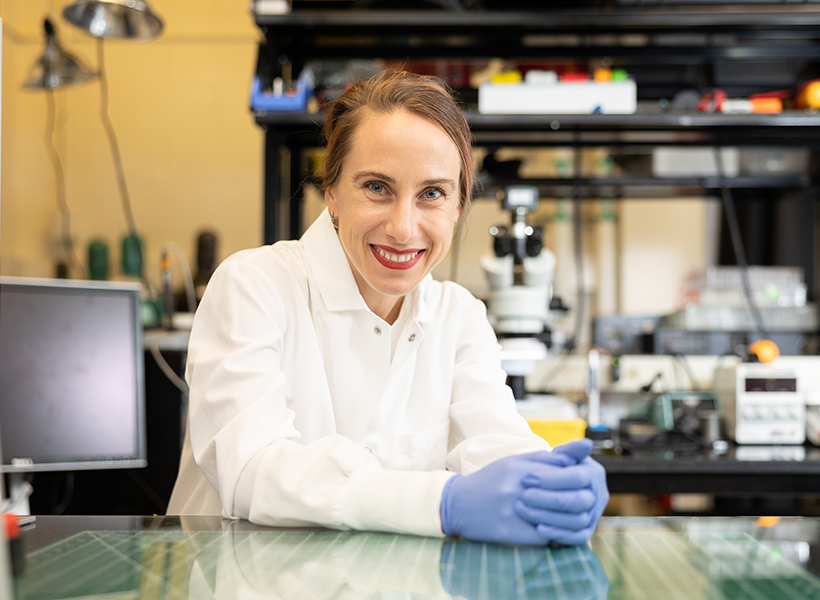

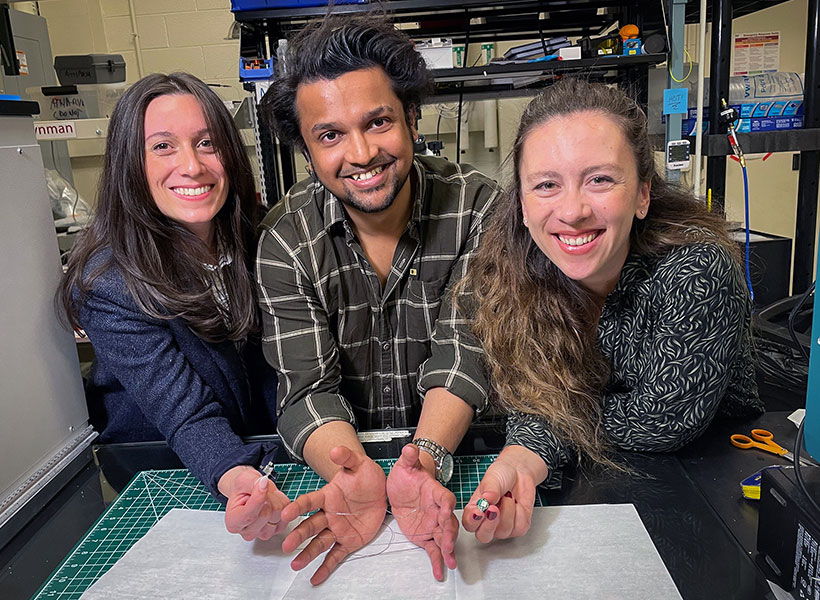

The development of these nanoparticles is described in the journal Nature Nanotechnology, in a paper by Polina Anikeeva, a professor in MIT’s departments of Materials Science and Engineering and Brain and Cognitive Sciences, graduate student Ye Ji Kim, and 17 others at MIT and in Germany.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a common clinical procedure that uses electrodes implanted in the target brain regions to treat symptoms of neurological and psychiatric conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Despite its efficacy, the surgical difficulty and clinical complications associated with DBS limit the number of cases where such an invasive procedure is warranted. The new nanodiscs could provide a much more benign way of achieving the same results.

Over the past decade other implant-free methods of producing brain stimulation have been developed. However, these approaches were often limited by their spatial resolution or ability to target deep regions. For the past decade, Anikeeva’s Bioelectronics group as well as others in the field used magnetic nanomaterials to transduce remote magnetic signals into brain stimulation. However, these magnetic methods relied on genetic modifications and can’t be used in humans.

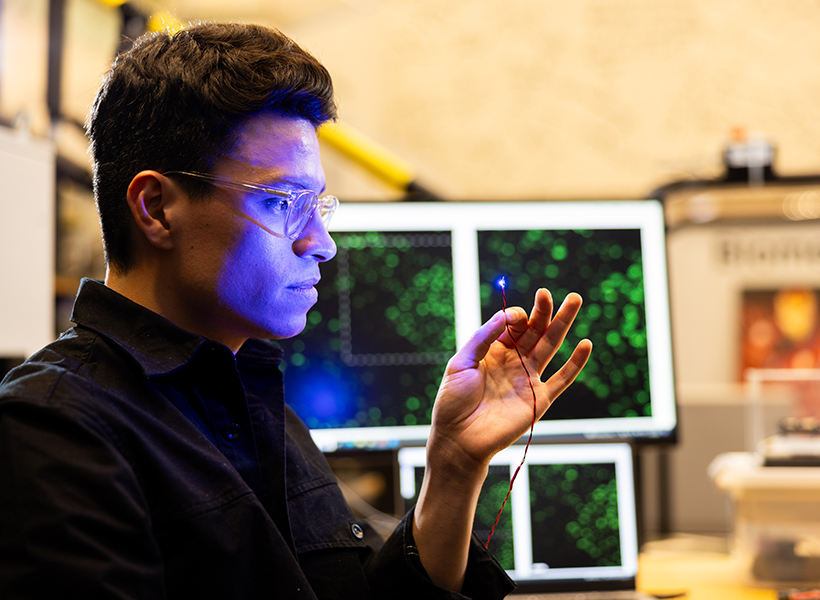

Since all nerve cells are sensitive to electrical signals, Kim, a graduate student in Anikeeva’s group, hypothesized that a magnetoelectric nanomaterial that can efficiently convert magnetization into electrical potential could offer a path toward remote magnetic brain stimulation. Creating a nanoscale magnetoelectric material was, however, a formidable challenge.

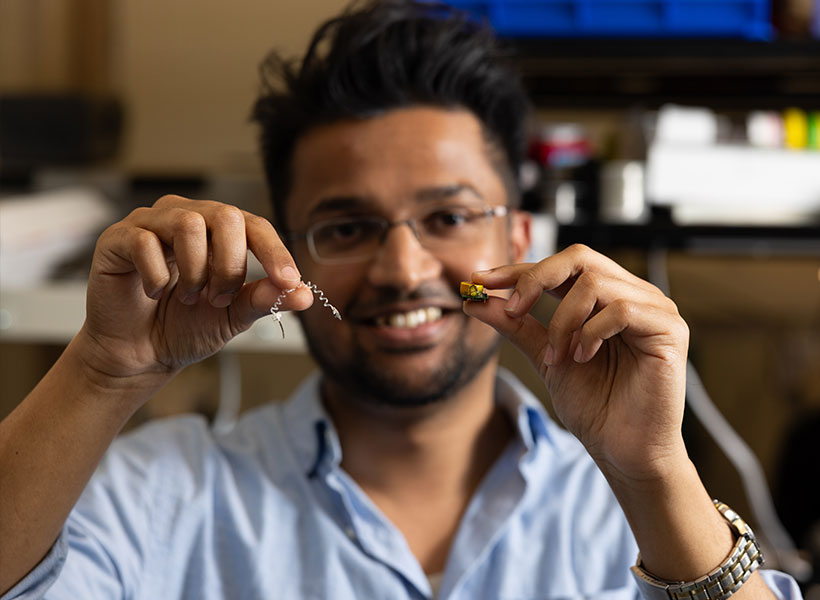

Kim synthesized novel magnetoelectric nanodiscs and collaborated with Noah Kent, a postdoc in Anikeeva’s lab with a background in physics who is a second author of the study, to understand the properties of these particles.

The structure of the new nanodiscs consists of a two-layer magnetic core and a piezoelectric shell. The magnetic core is magnetostrictive, which means it changes shape when magnetized. This deformation then induces strain in the piezoelectric shell which produces a varying electrical polarization. Through the combination of the two effects, these composite particles can deliver electrical pulses to neurons when exposed to magnetic fields.

One key to the discs’ effectiveness is their disc shape. Previous attempts to use magnetic nanoparticles had used spherical particles, but the magnetoelectric effect was very weak, says Kim. This anisotropy enhances magnetostriction by over a 1000-fold, adds Kent.

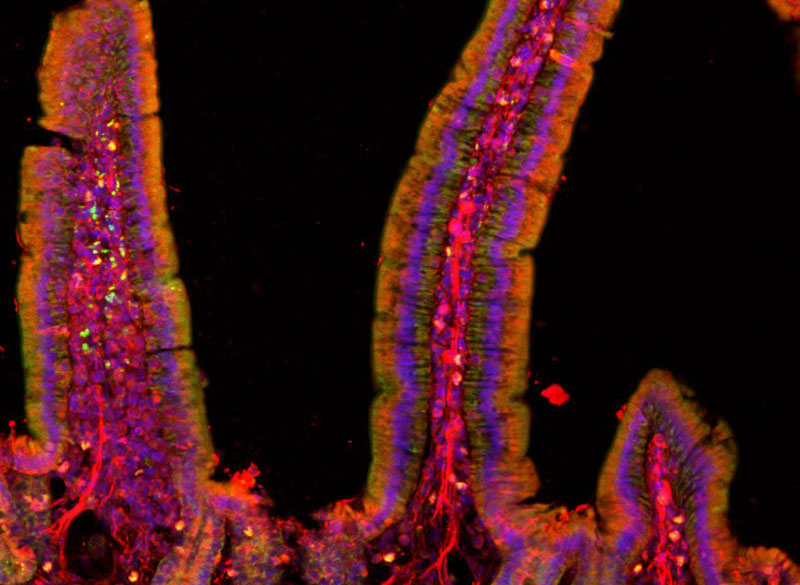

The team first added their nanodiscs to cultured neurons, which allowed then to activate these cells on demand with short pulses of magnetic field. This stimulation did not require any genetic modification.

They then injected small droplets of magnetoelectric nanodiscs solution into specific regions of the brains of mice. Then, simply turning on a relatively weak electromagnet nearby triggered the particles to release a tiny jolt of electricity in that brain region. The stimulation could be switched on and off remotely by the switching of the electromagnet. That electrical stimulation “had an impact on neuron activity and on behavior,” Kim says.

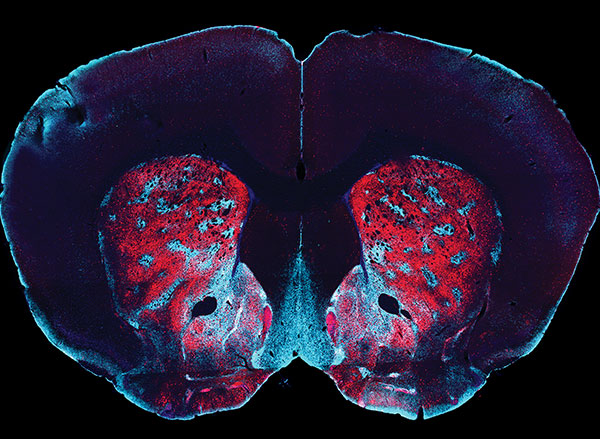

The team found that the magnetoelectric nanodiscs could stimulate a deep brain region, the ventral tegmental area, that is associated with feelings of reward.

The team also stimulated another brain area, the subthalamic nucleus, associated with motor control. “This is the region where electrodes typically get implanted to manage Parkinson’s disease,” Kim explains. The researchers were able to successfully demonstrate the modulation of motor control through the particles. Specifically, by injecting nanodiscs only in one hemisphere, the researchers could induce rotations in healthy mice by applying magnetic field.

The nanodiscs could trigger the neuronal activity comparable with conventional implanted electrodes delivering mild electrical stimulation. The authors achieved subsecond temporal precision for neural stimulation with their method yet observed significantly reduced foreign body responses as compared to the electrodes, potentially allowing for even safer deep brain stimulation.

The multilayered chemical composition and physical shape and size of the new multilayered nanodiscs is what made precise stimulation possible.

While the researchers successfully increased the magnetostrictive effect, the second part of the process, converting the magnetic effect into an electrical output, still needs more work, Anikeeva says. While the magnetic response was a thousand times greater, the conversion to an electric impulse was only four times greater than with conventional spherical particles.

“This massive enhancement of a thousand times didn’t completely translate into the magnetoelectric enhancement,” says Kim. “That’s where a lot of the future work will be focused, on making sure that the thousand times amplification in magnetostriction can be converted into a thousand times amplification in the magnetoelectric coupling.”

What the team found, in terms of the way the particles’ shapes affects their magnetostriction, was quite unexpected. “It’s kind of a new thing that just appeared when we tried to figure out why these particles worked so well,” says Kent.

Anikeeva adds: “Yes, it’s a record-breaking particle, but it’s not as record-breaking as it could be.” That remains a topic for further work, but the team has ideas about how to make further progress.

While these nanodiscs could in principle already be applied to basic research using animal models, to translate them to clinical use in humans would require several more steps, including large-scale safety studies, “which is something academic researchers are not necessarily most well-positioned to do,” Anikeeva says. “When we find that these particles are really useful in a particular clinical context, then we imagine that there will be a pathway for them to undergo more rigorous large animal safety studies.”

The team included researchers affiliated with MIT’s departments of Materials Science and Engineering, Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Chemistry, and Brain and Cognitive Sciences; the Research Laboratory of Electronics; the McGovern Institute for Brain Research; and the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research; and from the Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen, Germany. The work was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the McGovern Institute for Brain Research, and the K. Lisa Yang and Hock E. Tan Center for Molecular Therapeutics in Neuroscience.