This winter, seven new faculty members join the MIT School of Science in the departments of Biology and Brain and Cognitive Sciences.

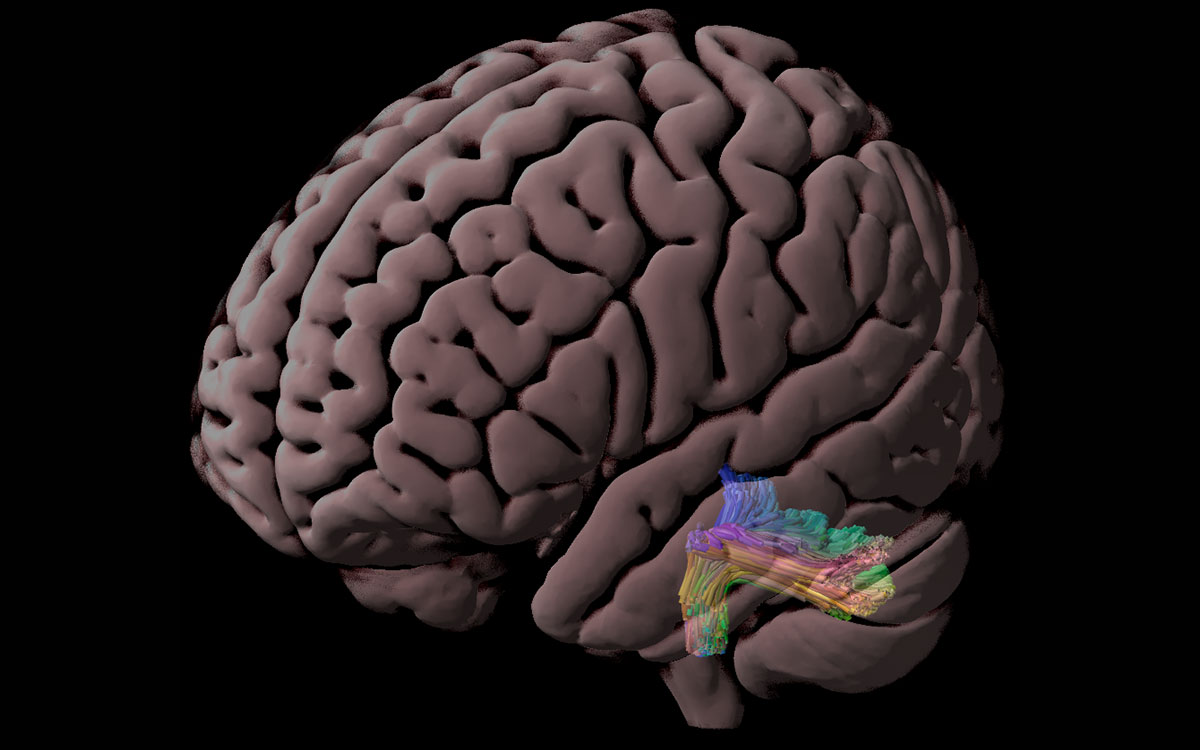

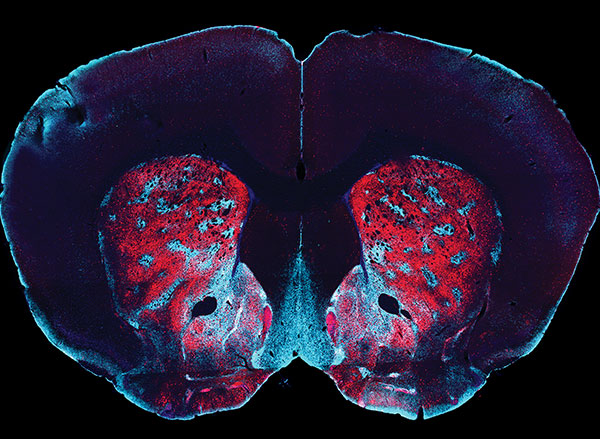

Siniša Hrvatin studies how animals initiate, regulate, and survive states of stasis, such as torpor and hibernation. To survive extreme environments, many animals have evolved the ability to decrease metabolic rate and body temperature and enter dormant states. His long-term goal is to harness the potential of these biological adaptations to advance medicine. Previously, he identified the neurons that regulate mouse torpor and established a platform for the development of cell-type-specific viral drivers.

Hrvatin earned his bachelor’s degree in biochemical sciences in 2007 and his PhD in stem cell and regenerative medicine in 2013, both from Harvard University. He was then a postdoc in bioengineering at MIT and a postdoc in neurobiology at Harvard Medical School. Hrvatin returns to MIT as an assistant professor of biology and a member of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research.

Sara Prescott investigates how sensory inputs from within the body control mammalian physiology and behavior. Specifically, she uses mammalian airways as a model system to explore how the cells that line the surface of the body communicate with parts of the nervous system. For example, what mechanisms elicit a reflexive cough? Prescott’s research considers the critical questions of how airway insults are detected, encoded, and adapted to mammalian airways with the ultimate goal of providing new ways to treat autonomic dysfunction.

Prescott earned her bachelor’s degree in molecular biology from Princeton University in 2008 followed by her PhD in developmental biology from Stanford University in 2016. Prior to joining MIT, she was a postdoc at Harvard Medical School and Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The Department of Biology welcomes Prescott as an assistant professor.

Alison Ringel is a T-cell immunologist with a background in biochemistry, biophysics, and structural biology. She investigates how environmental factors such as aging, metabolism, and diet impact tumor progress and the immune responses that cause tumor control. By mapping the environment around a tumor on a cellular level, she seeks to gain a molecular understanding of cancer risk factors.

Ringel received a bachelor’s degree in molecular biology, biochemistry, and physics from Wesleyan University, then a PhD in molecular biophysics from John Hopkins University School of Medicine. Previously, Ringel was a postdoc in the Department of Cell Biology at Harvard Medical School. She joins MIT as an assistant professor in the Department of Biology and a core member of the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard.

Francisco J. Sánchez-Rivera PhD ’16 investigates genetic variation with a focus on cancer. He integrates genome engineering technologies, genetically-engineered mouse models (GEMMs), and single cell lineage tracing and omics approaches in order to understand the mechanics of cancer development and evolution. With state-of-the-art technologies — including a CRISPR-based genome editing system he developed as a graduate student at MIT — he hopes to make discoveries in cancer genetics that will shed light on disease progression and pave the way for better therapeutic treatments.

Sánchez-Rivera received his bachelor’s degree in microbiology from the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez followed by a PhD in biology from MIT. He then pursued postdoctoral studies at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center supported by a HHMI Hanna Gray Fellowship. Sánchez-Rivera returns to MIT as an assistant professor in the Department of Biology and a member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT.

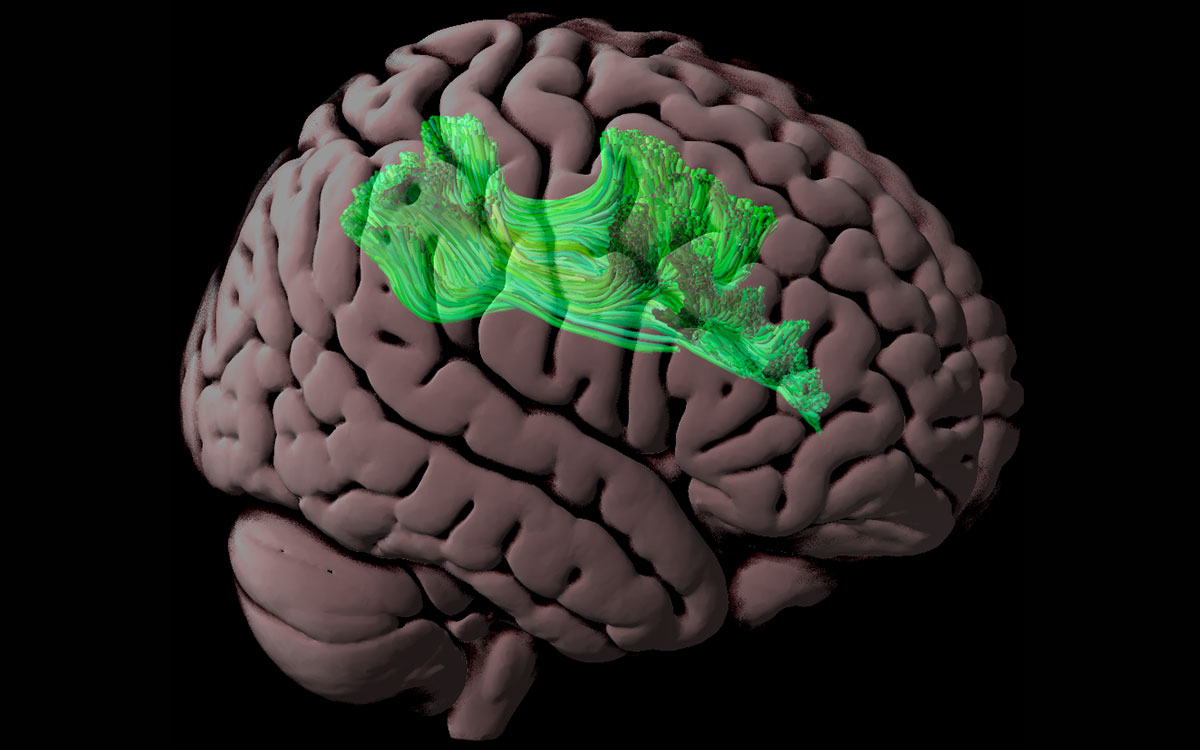

Nidhi Seethapathi builds predictive models to help understand human movement with a combination of theory, computational modeling, and experiments. Her research focuses on understanding the objectives that govern movement decisions, the strategies used to execute movement, and how new movements are learned. By studying movement in real-world contexts using creative approaches, Seethapathi aims to make discoveries and develop tools that could improve neuromotor rehabilitation.

Seethapathi earned her bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from the Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute followed by her PhD in mechanical engineering from Ohio State University. In 2018, she continued to the University of Pennsylvania where she was a postdoc. She joins MIT as an assistant professor in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences with a shared appointment in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the MIT Schwarzman College of Computing.

Hernandez Moura Silva researches how the immune system supports tissue physiology. Silva focuses on macrophages, a type of immune cell involved in tissue homeostasis. He plans to establish new strategies to explore the effects and mechanisms of such immune-related pathways, his research ultimately leading to the development of therapeutic approaches to treat human diseases.

Silva earned a bachelor’s degree in biological sciences and a master’s degree in molecular biology from the University of Brasilia. He continued to complete a PhD in immunology at the University of São Paulo School of Medicine: Heart Institute. Most recently, he acted as the Bernard Levine Postdoctoral Fellow in immunology and immuno-metabolism at the New York University School of Medicine: Skirball Institute of Biomolecular Medicine. Silva joins MIT as an assistant professor in the Department of Biology and a core member of the Ragon Institute.

Yadira Soto-Feliciano PhD ’16 studies chromatin — the complex of DNA and proteins that make up chromosomes. She combines cancer biology and epigenetics to understand how certain proteins affect gene expression and, in turn, how they impact the development of cancer and other diseases. In decoding the chemical language of chromatin, Soto-Feliciano pursues a basic understanding of gene regulation that could improve the clinical management of diseases associated with their dysfunction.

Soto-Feliciano received her bachelor’s degree in chemistry from the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez followed by a PhD in biology from MIT, where she was also a research fellow with the Koch Institute. Most recently, she was the Damon Runyon-Sohn Pediatric Cancer Postdoctoral Fellow at The Rockefeller University. Soto-Feliciano returns to MIT as an assistant professor in the Department of Biology and a member of the Koch Institute.